Confronted by news headlines about the inflation challenge and the battle to bring it under control, reasonable Australians may question both the logic of the proposed monetary policy settings of the RBA and the benign response of the Commonwealth Government.

The rhetoric in the RBA policy suggests that it intends to push interest rates higher and move our economy to the brink, but not into a recession. If only we could believe them!

Meanwhile we observe a complete lack of any counter inflation initiative from the Government. They have wasted a budget bounty (significantly higher than $4.3 billion) created from record export trading. This bounty amounted to a $40 billion budget turnaround in just six months, and it should have rightly been shared with low-income earners with the added benefit of being a counter inflationary policy. It now seems that the budget turnaround caught both Treasury and the Government by surprise and resulted in fiscal policy that is completely wrongly positioned to pull down inflation.

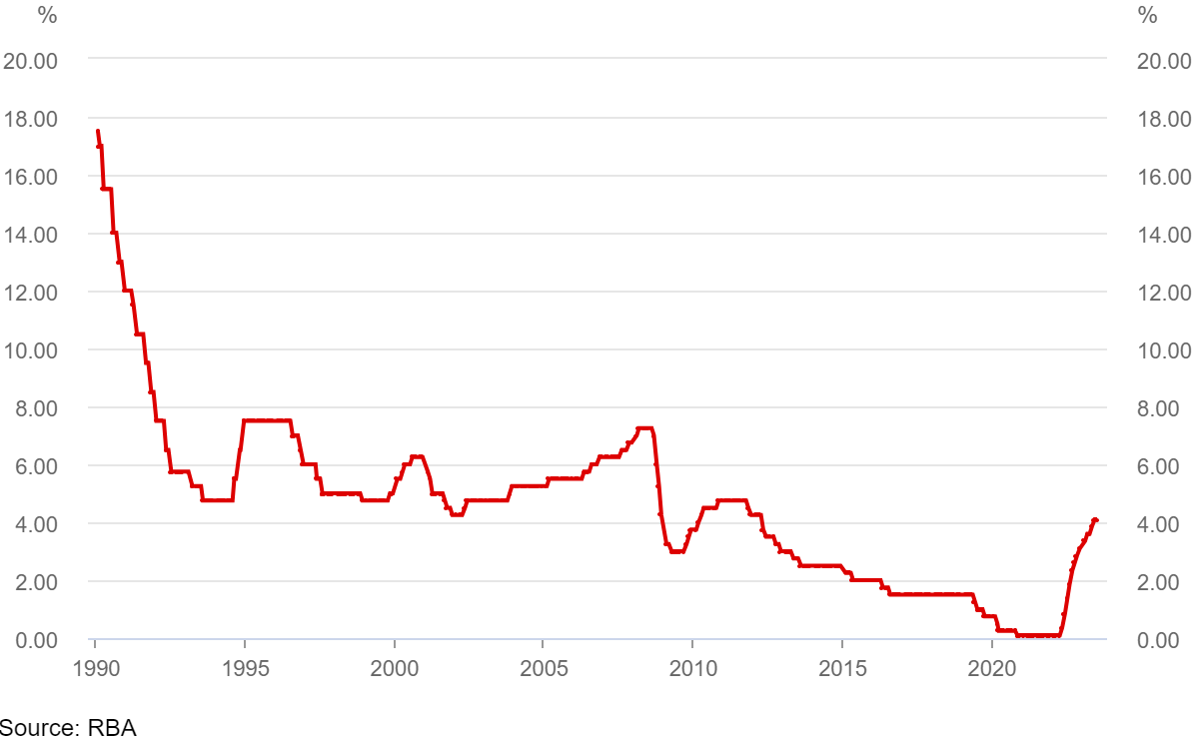

Do we need higher rates?

Australians can rightfully ask as to why, under RBA direction, should interest rates be pushed higher. This inflation fighting policy will have no real influence, given electricity prices (a driver of inflation) are set to rise by more than 20% from 1 July before falling in 2024? Further, what will rising interest rates do to lower the price of oil (petrol) when the supply of that essential commodity is manipulated by an international cartel supporting Russia in its war on Ukraine? Then, more crucially, how can higher interest rates lower the cost of rent when higher rates push up the cost of servicing mortgages of geared landlords?

RBA cash rate

The dogma of “economic group think” are easy to observe by everyone other than economists and bureaucrats. The dogma of economic theory drives thoughtless economic policy settings that belie common sense that suggests that the Government’s fight against inflation should have begun by slowing both wage and price rises. For instance, a calibrated tax adjustment for lower wage earners would have slowed wage push inflation and maintained employment. It will have appropriately checked the RBA’s policy aimed to create job losses. Wage increases outside productivity improvements, would therefore be directly influenced by Government income taxation adjustments.

A better solution

Given the extraordinary Commonwealth budget surplus to be reported for FY23, it is an absolute travesty that the Government did not move quickly to lower the tax rates for low-income earners. If they had then the Fair Work Commission having reviewed this and on the advocacy of the Commonwealth, could have held wages and throttled the likely broader wages push that will no doubt follow. A focused tax cut could have given more money into the hands of low-income workers than the Fair Work decision.

This observation leads me to observe that politicians, bureaucrats, and the ACTU do not understand that take home pay (after tax cashflow) is more important than pre-tax wage increases to an aged care worker, a healthcare worker, a childcare worker, a cleaner or a low-income service provider? Further, the RBA and Treasury do not understand that a recession will increase a fiscal deficit as payments rise with unemployment and tax collections fall. The movement into a fiscal deficit, in reaction to an economic downturn, is not theory – it is a fact. Therefore, protecting a short-term deficit independent of a strategic economic policy setting is hopeless.

In my view a managed economic downturn by the RBA, in the hope of pushing inflation down, will be much more costly than a thoughtful fiscal policy designed to lower inflation whilst maintaining economic growth. Further, in analysing the components of current inflation it is clear that the proposed rise in electricity prices is based on costs moves of six months ago, that have now reversed. So why support electricity prices higher and add to inflation across the economy when they will be reversed in 2024. That does not make sense!

The outlook for stocks

Self-directed investors are presented with a confusing short term economic outlook that is in contrast to Australia’s position in the fastest growing region of the world. To highlight this point, it is noteworthy that Treasury’s FY23 budget papers forecast that Australia’s major trading partners will grow at over 3 times the projected growth rate of Australia over the next two years.

Adding to the confusion is the observation that long term bond yields in Australia are trading at about 2-3% below reported inflation. Australia’s ten-year bond yield of just below 4% suggests that the bond market is less concerned with inflation than the RBA is. Indeed, it is interesting to reflect that when inflation last lurched above 6% in Australia (2021/22) the ten-year bond yielded 7%. Today’s long-term bonds have a negative ‘real yield’ compared to reported inflation and suggests that inflation will fall.

So, what does this ‘negative real’ ten-year bond yield mean for risk markets and particularly equities? The answer lies in understanding the effect on equity values resulting from the low or negative real returns presented in bond yields.

Normally a recession that flows from higher bond yields (inflation surging) has a significant effect on the value of equities as company earnings fall concurrent with a decline in the price earnings ratio (PER) of the market. However, in this peculiar cycle, with inflation expected to fall no matter what the RBA does, the likely earnings decline of FY24 will not be magnified in the market by a generally lower PER. In other words, any decline in the Australian share market will be moderate. Further, when earnings recover, as they will, given the long-term tailwinds of Australia’s trade and population growth, the market will bounce strongly from higher earnings off elevated PERs.

The RBA isn't independent, get over it

Australians in general, especially low-income earners and investors, must wonder how much better Australia would be if there was a constant and sharp focus on sustainable growth. That growth focus requires our bureaucracies to discuss and develop coordinated policies. In particular they should break away from the dogmatic belief that the RBA must be independent of Government. It cannot be independent because the RBA is the largest single creditor of the Government owning about 40% of Commonwealth Government debt.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.