Of all the lessons learned during the pandemic — wash your hands thoroughly, avoid crowded lifts, working from home can be productive — perhaps the most consequential lesson for companies is now obvious in hindsight: relying on single links in the global supply chain was a mistake.

Major components of the supply chain fractured during the COVID-19 crisis, resulting in shortages of everything from medical supplies and equipment to furniture and auto parts. Geopolitical events also entered the fray as US-China tensions and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine underscored the risks of relying too much on one place for critical supplies, including energy, food, and computer chips.

As my colleague Julian Abdey recently noted:

“With the rapid spread of globalisation over the past few decades, companies moved their manufacturing operations to the cheapest and most efficient countries. That was great for company profits and consumer prices. But what we found out more recently is that when supply chains get disrupted it can cause real problems. For example, Europe has realised it was too dependent on Russia for natural gas. And I think the same is true for other products like computer chips. The world is too dependent on Asia, and Taiwan in particular, for semiconductors.”

Reshoring replaces offshoring

Fast forward to 2023, and many companies — in some cases spurred by massive government subsidies — are taking big steps to diversify their supply chains, focusing on reliability and robustness over cost and efficiency. That means bringing some manufacturing back home, or “reshoring” and moving some of it to other countries.

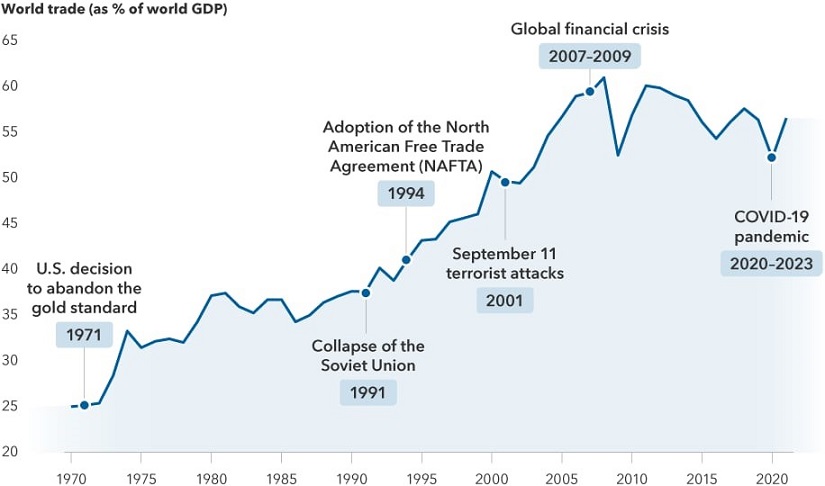

The trend has raised questions about whether the world is moving into a period of de-globalisation. However, based on trade activity in recent years, the new path looks more like a measured adjustment to global supply chains, partially interrupted by the pandemic and the 2007–2009 financial crisis.

Globalisation marches on — at a different pace

Sources: Capital Group, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), World Bank. World trade is calculated as the sum of exports and imports of goods and services and is represented above as a share of global gross domestic product. Trade data as of 2021.

Rob Lovelace, Portfolio Manager at Capital Group says:

“When we talk to companies and look at the data, we are not seeing what I would call de-globalisation. I think it would be more accurate to call it a rewiring of global supply chains. And I don’t think it’s really all that dramatic when you consider the rapid growth of digital trade, which is harder to track using traditional metrics, as opposed to physical trade.”

In fact, there is ample evidence that many companies are becoming more global as they seek to create redundant supply chains. The poster child for this development is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company or TSMC, the world's largest semiconductor foundry. To expand its global reach, TSMC is building new manufacturing plants in Arizona and Japan. Semiconductors have become such a sensitive issue, given their use in the defense industry, that the US government has placed aggressive restrictions on where and how they can be exported.

Other examples abound in the tech sector and elsewhere. Apple announced in September that it would start producing the iPhone 14 in India, adding to its manufacturing capabilities in China, the Czech Republic and South Korea among others. In the auto sector, Tesla added to its US and China manufacturing hubs last year by opening its first European outpost in Gruenheide, Germany.

In the energy sector, Texas-based ECV Holdings has announced plans to build a power plant for industrial parks near Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, supplied primarily by US liquified natural gas. Meanwhile, the list of US companies establishing new manufacturing plants at home has grown dramatically in recent years to include General Motors, Intel and US Steel — fueling hopes of an American industrial renaissance.

The China+1 strategy

Amid this drive to diversify supply chains, a common misconception is that China may be displaced as the world’s largest manufacturing base. As my Capital Group Portfolio Manager colleague Winnie Kwan has observed, many companies are shifting to a “China+1 strategy” by maintaining operations in China while adding new facilities elsewhere. Incremental investments in China are likely to focus on serving mainly the domestic market, while additional investments in other locations cater to the rest of the world.

“A key question is whether the China+1 strategy will be scalable or not. Can you add a new plant in India or Mexico, for example, and scale up production as needed? Is the labour and power supply sufficient? Is logistics infrastructure in place? Can management handle the added complexity? Those are the questions I am focusing on as we research these developments and look for investment opportunities. Not every company is going to get it right” she says.

Indeed, the flow of incremental investments is an important metric for investors to track. According to a 2021 survey of foreign companies doing business in China conducted by AmCham Shanghai, the top destinations for redirected investments were Southeast Asia, Mexico, India, and the United States. However, only 63 of the 338 companies surveyed said they had such plans, which suggests the process of reshoring may be slower and more deliberate than some market participants are expecting. Winnie observed that:

“It could take a decade for companies to fully transition. But the process has certainly started, and I think it will be one of the more important investment themes of the 2020s.”

Southeast Asia is well positioned for the rewiring of global supply chains

Source: AmCham Shanghai 2021 China Business Report, published September 22, 2021.

Based on a survey of 338 foreign companies doing business in China. Of those companies, 63 said they were redirecting investments from China to other locations, including Southeast Asia, Mexico, India and the United States, among others.

Who benefits from reshoring?

With such a large undertaking, the investment implications are widespread across a number of sectors and geographies. Here are four areas expected to benefit from reshoring in the years ahead.

1. India Thanks to its proximity to China, a well-educated labour force, and a fast-growing, business-friendly economy, India may be the best-positioned country to capitalise on supply chain diversification. India’s government has taken bold steps to encourage the expansion of manufacturing operations, particularly in the smartphone space, where Apple works with contractors such as Foxconn to build the latest iPhones. The manufacturing sector is expected to accelerate over the next decade, driving growth in the Indian economy and boosting other industries such as banking, energy, and telecommunications.

2. Mexico Similar to India, Mexico’s proximity to one of the world’s largest economies makes it an attractive base for expanded manufacturing and logistics operations. Many US companies flocked there in the 1990s after the adoption of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). That process has only accelerated under a revamped trade deal, the US/Mexico/Canada Agreement (USMCA), ratified in 2020.

Mexico’s annual exports to the US have increased sharply in recent years. Although much of that is due to the influence of American companies, China is also ramping up in Mexico. For example, Hisense Group, one of China’s largest appliance makers, is currently building a $260 million industrial park in Monterrey, aiming to produce refrigerators, washing machines and air conditioners for the US market. In the auto sector, BMW and Nissan have also recently expanded their capabilities south of the border.

3. Automation providers One of the biggest hurdles to diversifying the world’s manufacturing capabilities is a chronic labour shortage, especially in developed economies. Automation powered by artificial intelligence (AI) is likely to provide an answer to this problem, says my colleague, portfolio manager Mark Casey. He believes many Asian countries are setting the trend with high rates of industrial automation, with the US and Europe expected to follow. Both regions have room to grow, proving a bright outlook for top companies in the global robotics industry, including Japan’s Keyence, France’s Schneider Electric and Switzerland’s ABB Ltd. Amazon is also developing its own impressive AI-driven technology.

“Amazon has a new robotic picking-and-packing device called Sparrow that can grab more than 60 million different products and pack them into shipping boxes — completing each pick in a matter of seconds. Just seven years ago Amazon’s experimental robots could handle only a small number of items, and each pick would take a couple minutes. I think this sort of technology is coming along sooner than we think, and I don’t see it accounted for in the stock prices of any major American or European company” Mark recently noted.

Automation, powered by smart robots, is ready for take-off

Sources: Capital Group, International Federation of Robotics. As of 2022.

4. Multinationals Capital Group portfolio manager Jody Jonsson recently noted that:

“Although it may seem counterintuitive, the same multinational companies that benefited most from the rapid pace of globalisation in the past may be best equipped to navigate the brave new world of re-globalisation. The world’s largest and most dominant companies rose to that position for a reason — they often have the experience and resources to adapt to changing trade patterns better than smaller companies operating in single markets.”

In Jody’s view, well-managed multinational companies will remain global in their production facilities and customer bases, but they will increasingly build more local redundancy into their operations. She calls it ‘multi-localisation.’ That includes bringing some parts of the supply chain back to the US, continuing to outsource other parts and establishing new production facilities in key areas throughout the world. As Jody observed:

“If there is one lesson we’ve learned from the COVID crisis, it’s that companies must have diverse supply chains. We aren’t there yet, but the process is well underway.”

Matt Reynolds is an Investment Director for Capital Group Australia, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article contains general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Please seek financial advice before acting on any investment as market circumstances can change.

For more articles and papers from Capital Group, click here.