For much of my career in the 1980s, I specialised in global capital markets, arranging transactions worth billions of dollars on behalf of my employers, the Commonwealth Bank and State Bank of NSW. It was great fun, travelling the world at a time when Australian borrowers started using a wide range of offshore funding markets for the first time, and the Australian dollar became desirable for overseas investors.

But the Eurobonds we issued helped rich global investors to evade tax by hiding their wealth from tax authorities.

An excellent book called Moneyland by investigative journalist Oliver Bullough examines how global bankers developed ways for wealthy people to hide their investments, entering the world of oligarchs and thieves and corrupt governments. He demonstrates how powerful bankers and government officials in places like the Caymans, Channel Islands, Jersey, Ukraine, Russia and Luxembourg facilitated money laundering and hid billions on behalf of the world’s wealthy, making the bankers rich in the process.

The Eurobond market started in London when bankers developed a brilliant idea that created a financing and investment bonanza. Says Bullough:

“The idea of an asset being legally outside the jurisdiction that it is physically present in, is absolutely central to our story. Without it, Moneyland would not exist.”

The pivotal genius of the design was the use of bearer bonds. Whoever possessed the bonds, owned them. There was no register of ownership and no record of the investment. The bonds could be carried anywhere and sold, and the coupons snipped off to collect interest. This grand scheme was not only favoured by wealthy people, but the ordinary folk such as the legendary ‘Belgian dentists’ with a few thousand dollars to invest could buy bearer bonds at a local bank.

Most Australians have little need for dodgy schemes

Reading the book made me think about the use of such schemes in Australia. Few people would expect to go to a financial adviser in Australia and hear about dodgy schemes to evade tax. There’s a good reason for this. We have plenty of ways to avoid paying tax that are completely legal and commonly used.

But it raises the question of where tax revenue will come from in future. The 2023 Intergenerational Report (IGR) has triggered a debate (again) about the future reliance on personal income tax to fund budget expenditures, and the burden this will place on future workers. Former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry called it an ‘intergenerational tragedy’, adding in an ABC Radio interview:

“It’s the young people who are going to be the workers of the future. People who are weighed down with HECS debt, who are going to have to repay a mountain of public debt, who are dealing with the consequences of climate change … who are facing diminishing prospects of ever being able to afford a home of their own. These poor buggers are also going to be the ones who are facing ever-increasing average rates of income tax.”

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), there are 4.1 million retired Australians, and they have at least as many children expecting to inherit their wealth. That's millions of voters with a vested interest in the current system. A recent speech at the Press Club by Treasurer Jim Chalmers shows he recognises the problem although he avoids any meaningful policies to support his ambition.

“In fact, around 40% of the projected increase in spending that’s outlined in the IGR is due to us getting older. Here, at this generational fork in the road, we can shape the future on our terms. We can turn these turbulent twenties into the right kind of defining decade.”

Given the outcry about the strain on future generations, what are some common ways Australians avoid tax which might demonstrate why the Government is reluctant to make major changes?

(Tax ‘evasion’ means concealing income or information from tax authorities whereas tax ‘avoidance’ is legally reducing tax).

10 common ways to avoid tax

Millions of Australians are well-practiced at avoiding tax. It’s almost a national pastime. These techniques are not complex derivatives, offshore companies, special purpose vehicles or money hidden in the Cayman Islands. These are not only legal but part of every financial advisers’ kitbag.

1. Invest through superannuation

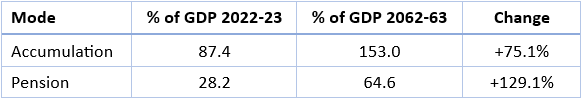

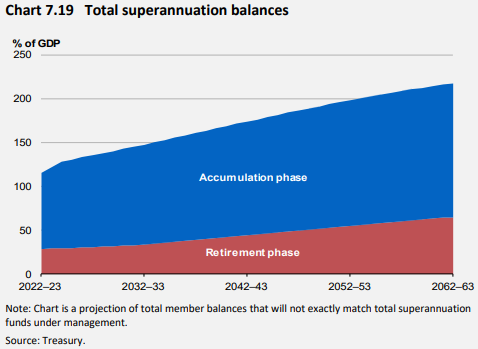

According to the IGR, total superannuation balances will grow from 116% of GDP in 2022-23 to 218% by 2062-63, as shown below. Despite the ageing of the population, the vast majority of assets will continue in the accumulation phase, but assets in tax-free pensions will reach two-thirds of GDP from the current 28%, an increase of 129%. Accumulation assets will increase by a more modest 75%. That's more money paying less tax.

Future assets in retirement phase are significantly higher as the system matures and more Australians will have received the Superannuation Guarantee for most of their careers, rising to 12% from 1 July 2025. The proportion of people drawing a superannuation pension will increase from 8% to 19% of the population over the next 40 years.

Despite numerous rule changes, the current Transfer Balance Cap is $1.9 million per person, expected to rise to over $2 million at the next indexed increase on 1 July 2024. So a couple can soon hold over $4 million in assets in a tax-free pension. Assuming it is simply placed in term deposits at 5%, that’s $200,000 a year tax free.

For people too young to be eligible for a superannuation pension, the system offers many ways to avoid or reduce tax, such as salary sacrifice, spouse and co-contributions.

2. Leverage into the family home

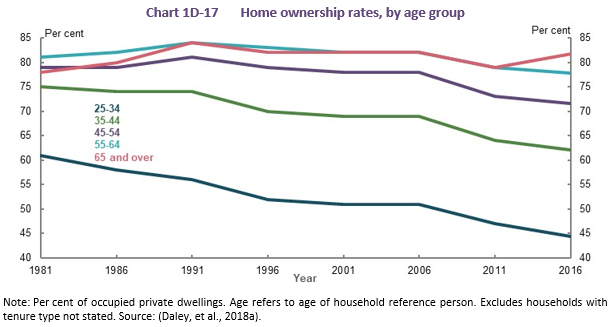

It’s the sacred cow, the place where most Australians have accumulated their tax-free wealth through high leverage. And the older a person, the more likely they are to own their own home. The chart below from the Retirement Income Review shows home ownership for people aged 65 and over is higher now than 40 years at about 82%, while it is significantly lower for people aged 24 to 34 years.

In addition to avoiding tax on the sale of their biggest asset, the family home is excluded from social security tests such as eligibility for the age pension.

Who needs a Caribbean tax haven when they live in and own a piece of Australian residential real estate? The tax treatment is the main reason why Australians have the most expensive houses in the world after Hong Kong. According to Demographia, Sydney is the second least-affordable housing market in the world, ranking 93rd in affordability out of 94 markets.

3. Earn tax-free income outside super

The general tax-free threshold for Australian residents is $18,200. However, a combination of the Low Income Tax Offset and the Seniors and Pensioners Tax Offset pushes the effective tax-free threshold to $29,783 a person. A couple can earn $59,566 outside superannuation and pay no tax.

Many older people should consider moving their investments out of super to avoid the so-called ‘death tax’ payable when superannuation is inherited by a non-dependant.

4. Pass wealth to the kids

There are no inheritance or death taxes in Australia, and beneficiaries do not need to pay tax on money received as part of a will. In many other countries, inheritance taxes are major estate planning factors. Generally, capital gains tax (CGT) does not apply when a dwelling is inherited, but it may apply later when the property is sold. An inherited property may retain its principal place of residence status but this depends on the treatment by the deceased and beneficiary. There is an exemption from CGT if a property was the main residence of the deceased and it is sold by the beneficiary within two years, or acquired before September 1985. There are conditions allowing the extension of this two-year rule.

There is a super ‘death tax’ when the taxable component of superannuation is inherited by a non-dependant, taxed at 15% plus the Medicare levy. While a spouse is always considered a dependant, adult children are not. The obvious way to avoid this tax is to withdraw the money from superannuation tax-free before death and leave it outside the superannuation system. Some people appoint an enduring power of attorney which permits the attorney to withdraw money in cases where someone loses capacity near death.

5. Receive franking credits

There is a lot of misunderstanding about franking credits, and a longer explanation is in this article called Franking Credits Made Easy.

There is a key change coming in the Stage 3 tax cuts which are expected from 1 July 2024. The 30% tax rate is legislated to apply for the $45,000 to $200,000 tax bracket.

Our tax system allows tax already paid by a company to be refunded to a shareholder. For example, if a company makes a profit of $100 and pays company tax of $30 at the 30% rate (smaller companies pay at 25%), the company may fully distribute the profit after tax of $70 by declaring franked dividends to shareholders. The ATO ‘imputes’ or ‘credits’ the tax paid by the company to each shareholder.

When shareholders complete their tax returns, they add the $70 of dividend to the $30 of franking to declare the $100 of taxable income. The $100 of company profit is then subject to personal marginal income tax rates. Up to the $200,000 threshold (or lower for smaller incomes), shareholders pay tax on the $100 at 30% and claim the $30 that was already paid by the company as a tax credit. The shareholder pays no additional tax when receiving a fully franked dividend.

6. Negative gear investments

The term ‘negative gearing’ is not mentioned in any tax legislation, but it is familiar to millions of Australians as a technique to manage or eliminate tax. Where expenses, including interest paid on borrowings, on an investment are greater than income earned on the investment, the loss can be charged against other income, such as salaries and wages. The asset does not need to be residential property but that is the most common personal use.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) estimates that the annual cost to the budget of housing investors claiming deductions against other income will exceed $20 billion a year by 2032.

7. Top up with insurance (investment) bonds

Investment or insurance bonds are offered by life insurance companies and are subject to company tax rules. Tax is payable at the company tax rate, and if the bond is held for at least 10 years, earnings are not included in the investor’s tax return. These bonds are commonly used to pay for a child’s education, often purchased by grandparents, with no need to record or declare the earnings if held for 10 years. While this investment is not strictly ‘tax free’, the individual holder does not need to pay tax. Previous articles provide more detail including tax treatment if withdrawn prior to 10 years.

8. Distribute income using family trusts

A family trust is a discretionary trust used to hold the wealth and assets of a family. A trust is a legal structure under which the trustee holds the legal title to investments for the benefit of other people, the beneficiaries. The trustee has the discretion to distribute to the beneficiaries who are usually members of the same family. Trust income distributed is taxed at the marginal income tax rate of the beneficiary. Generally, the trustee allocates more distribution to the family member with the lower marginal income tax rate, thereby reducing the tax paid on the trust income. This might include adult children who have no other income, or are below the income-free threshold, and therefore pay no tax.

9. Use favourable capital gains treatments

CGT is only incurred when an asset such as an investment property or shares is sold, giving the taxpayer more control over the timing of a liability than on personal taxable income. Capital gains are reported in the normal income tax return and any capital losses can offset the CGT. Another asset can be sold at a loss to offset a CGT liability and a CGT discount of 50% can be claimed for assets held more than a year.

The Australia Taxation Office is also generous in allowing taxpayers with a capital gain to select a favourable purchase price using several methods, including First In First Out (FIFO), Last in First Out (LIFO) and Average Cost. This discretion can significantly reduce the CGT liability.

Care should be taken with investments to ensure a capital gain is not converted to taxable income. For example, an investment in a managed fund in June that receives a distribution in July may be converting capital to taxable income. If the unit price is say $1.00 and then a 10 cent per unit distribution is made on 30 June, the unit price will fall to 90 cents at the beginning of July. The 10 cents will be taxable income in the hands of the unit holder.

In superannuation, it is possible to avoid CGT on an asset bought during the accumulation phase but sold after a switch to pension mode where no tax is payable. There are tips to doing this correctly as explained here.

There is also a lifetime exemption from CGT of $500,000 from the sale of an active small business.

10. Make donations to charity

Of course, nobody is proposing a change to the tax deduction of charitable giving, but no list of ways to reduce or avoid tax should overlook the most altruistic. A tax-deductible donation to an Australian Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) is a simple way to reduce tax. Public and Private Ancillary Funds are structures that generate an immediate tax deduction with the donations made later. It requires a tax invoice and the correct status of the charity can be checked on the Australian Business Register here.

Keep it legal

In Australia, there are plenty of ways to avoid tax without incurring the wrath of the ATO or hiding money in a Caribbean island. However, given the revenue needs outlined in the IGR, and Treasurer Jim Chalmers' desire to "shape the future on our terms" and "turn these turbulent twenties into the right kind of defining decade”, then at some point, tough decisions will be needed on many of the ways tax is collected and more importantly, not collected.

But for now, anyone using these opportunities should ensure every step is taken with full knowledge of the correct tax treatment or penalties may be imposed. The tax treatments outlined in this article are common but there are procedures to follow, and guidance from a tax professional is always beneficial.

Graham Hand is Editor-At-large for Firstlinks. This article is general information, not taxation or personal advice, and is based on an understanding of relevant legislation. Individuals should seek advice from a financial advisers or tax accountant before embarking on any of the strategies outlined in this article.