So it's gonna be forever

Or it's gonna go down in flames

You can tell me when it's over

If the high was worth the pain

Got a long list of ex-lovers

They'll tell you I'm insane

'Cause you know I love the players

And you love the game

-Taylor Swift, Blank Space

Yes, Taylor, we loved the players and we loved the game. Swiftly, it's over, leaving a blank space.

It looks easy from the outside, but asset management is a tough game. Winners can win big, but there are far more strugglers. In a concentrated portfolio, a heavy overweight position in a losing stock can mean “it’s gonna go down in flames”.

Recently, an unprecedented number of fund managers have closed their businesses or some of their funds, including:

- KIS Capital

- Sigma Funds

- JCP Investment Partners

- Dual Momentum

- Janus Henderson Australian equity funds

- MHOR Asset Management

- Discovery Asset Management

- Denning Pryce

- Adam Smith Asset Management

- Concise Asset Management

- Arnhem Investment Management

- Ellerston Global Macro

- Colonial First State Global Asset Management ‘Core’ funds (transferred to other managers)

- UBS Asset Management Australian equity funds (transferred to Yarra Capital)

- Altair Asset Management

For many years, I managed the ‘alliance’ business for Colonial First State (CFS), where we would partner with portfolio managers to establish new operations. We saw all types of potential come across our desks, from a couple of people wanting to set up their own boutique, through to large global managers establishing an Australian business.

How hard can it be? While there are some overlaps in the following reasons, here are 10 industry hurdles to overcome. These may or may not apply to the above names.

1. The growth of index investing

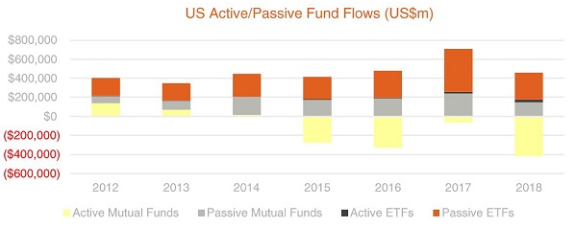

In 2018 in the US, passive index funds (including unlisted mutual (managed) funds and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)) enjoyed a net inflow of US$431 billion, while active mutual funds experienced net outflows of $418 billion, as shown below. Given the large fee difference, that represents a loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in fees to the asset management industry. It's also become widely-accepted wisdom that most active managers do not beat the index.

In Deloitte’s 2019 Investment Management Outlook, 16 of the top 20 global funds by net flows were passive mutual funds and ETFs, gathering a net US$143 billion.

Source: Bloomberg and BetaShares

In the US, it is estimated that 34% of mutual funds and ETFs are passively managed. This number is only about 12% in Australia, but momentum is well-established. Most local ETFs are index-based and in the final quarter of FY2019, ETFs listed on the ASX exceeded $50 billion for the first time.

It is not only the fund flows that hurt active managers, but the price competition. Institutions can achieve index management on large portfolios for 1 or 2 basis points (0.01 to 0.02%), forcing active managers to compete as low as 20 basis points (0.2%). It is difficult to finance a fully-functioning active operation of portfolio managers, analysts and support functions at such low fees unless billions of dollars are held. Even a good $250 million mandate would bring in only $500,000, which would barely cover the cost of a senior portfolio manager.

2. In-house management by large institutions

Many of the largest superannuation funds in Australia are boosting their in-house asset management capabilities and withdrawing mandates from external managers. The most high-profile in the last year was AustralianSuper’s move of $7.7 billion internally from Perpetual Investments, Fidelity International and Alphinity Investment Management. These are not small boutiques but long-term successful fund managers with substantial operations of their own.

CIO, Mark Delaney, explained the change:

“We found there was an overlap in the shares held by the different managers. Over the last three or four years, we found that in Australian equities, in terms of the stocks held, we had the same stocks in the top 50 and these holdings did not change much. This is the nature of the Australian market. It has a narrow number of stocks and a narrow number of sectors.”

Currently, about 58% of AustralianSuper’s Australian equities assets are managed internally, and most of the external management is in the cheaper index funds.

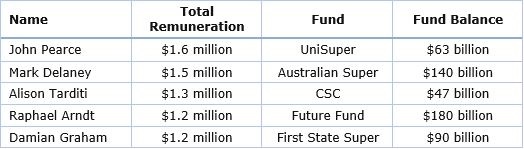

The large superannuation funds now attract top talent receiving market-comparable salaries. While most of the leading CIOs could earn more in the private sector, the super sector’s guaranteed inflows, stability of funding, lack of need to continually pitch for new money and clarity of a single stakeholder appeal to many. The top-earning CIOs in Australian super funds (according to Investment Magazine) are:

3. Extreme variations in performance

Most investors are prepared to tolerate short-term underperformance from their fund manager, but others are impatient and bale out after a year or two. It’s worse when the manager has a significantly-poor year.

The financial year 2018/2019 experienced some rapid price rises in companies where investors were willing to bank on future growth, including the Top 5 for the year: Nearmap (ASX:NEA) up 233%, Clinuvel (ASX:CUV) up 206%, Afterpay (ASX:APT) up 168%, Magellan (ASX:MFG) up 119% and Appen (ASX:APX) up 109%.

Managers without these types of high flyers in their portfolio have experienced significant underperformance as they stick to their valuation principles. For example, consider the NAOS Small Cap Opportunities Company (ASX:NSC). It operates under a Listed Investment Company (LIC) structure. In its April 2019 Investment Report, in explaining why it has not invested in these big winners, it says:

“… the main concern for us is the significant faith that is being placed in the earnings trajectory of these businesses for many years into the future.”

As NAOS admits, the permanent capital of a LIC has protected it from heavy redemptions, due to this relative performance.

The Zenith 2019 Australian Shares Long/Short Sector Report for the year to 31 March 2019 reported an average return of 5.2% for the funds they rate, versus 11.7% for the S&P/ASX300 Accumulation Index. Zenith Investment Analyst Jacob Smart said:

“In 2018, the spread between the cheapest and most expensive stocks reached record highs and, even after the fourth quarter correction last year, remained at elevated levels. The cheaper segment of the market continued to become even cheaper throughout 2018.”

4. Managing with an out-of-favour style

Every fund manager must have fundamental beliefs about how to manage money and select investments. The most obvious style variation is ‘growth versus value’, and others such as ‘small cap versus large cap’ and ‘long/short versus long only’ move in and out of favour.

Growth has been rewarded for at least five years as the market chases companies with blue sky earnings potential, even when the revenues are not yet realised. The WAAAX stocks are all classic examples, where the market assigns massive P/E valuations and two of them do not even make a profit. Value managers look for companies which are inexpensive relative to a fundamental value, with sustainable earnings and low valuations, such as ‘buying $1 of value for 80 cents’.

According to JP Morgan, there has never been a worse time to be a value investor. In the US, value stocks are trading at the largest discount to the market in history. They measure the median forward P/E ratio of value stocks in the S&P500 and compare it with the broader S&P500 and the spread is now at a record 7 points.

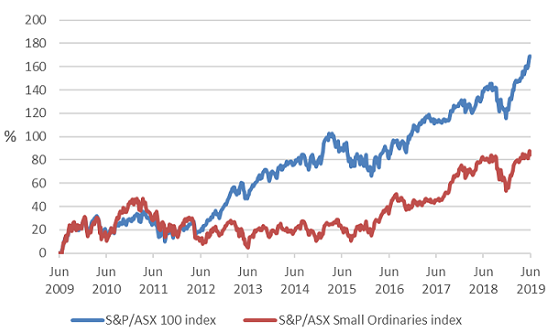

Another segment which is out-of-favour is small cap investing, trailing large cap. As shown below, in the last 10 years, the S&P/ASX100 index has substantially outperformed the Small Ordinaries index, leaving many small cap managers struggling to deliver decent returns.

S&P/ASX Small Ordinaries Index vs S&P/ASX100 Index, 10 years to 30 June 2019

Source: Bloomberg, CFSGAM. Cumulative total returns 30 June 2009 to 30 June 2019.

Long/short investing is also battling on with many casualties. KIS Capital launched in 2009 and its funds peaked at around $300 million, but it closed recently after a difficult 2018 where results were “disappointing”. It advised its clients:

"Given the state of the market, KIS Capital directors have concluded that the best course of action at this point is for us to close both funds and return capital to all investors on an equitable basis.”

5. Inadequate marketing and distribution

Build it and they may not come. Most fund managers would prefer to sit at a desk all day, study their screens and analyse companies. However, especially in a small boutique which relies on the profile of one or two managers, they must wear out the shoe leather and tell their story. It’s a tricky balance. Their main skill may be stock picking, but they need to become extrovert marketers, not simply hire a Business Development Manager with a Rolodex. They must establish themselves as thought leaders.

Research by leading consultants, Tria Partners, concludes:

“… thought leadership is the single most important factor that underpins improvement of buyers’ understanding and perception of external asset managers – i.e. it’s the most value-adding activity marketing can undertake.”

Significant resources are needed to cover institutions, middle market gatekeepers and retail sectors properly. Many fund managers have realised in recent years that they need a direct conversation with end investors, and they particularly target SMSF trustees. The combined value of ETFs and LICs listed on the ASX is now $100 billion, and SMSF trustees often manage their own portfolios directly through the listed market. Previously, some managers confined their marketing to institutional investors, believing it was better to win a $100 million mandate than source thousands of smaller investments. Now those mandates are drying up, the fees are lower and the competition is intense. Marketing through dealer groups to find financial advisers is also not enough, as increasingly, advisers are acting independently and not following the central directive of an Approved Product List.

Tria released the following research on the most effective forms of marketing.

6. Lack of institutional and retail investor support

When MHOR Asset Management announced the closure of its Australian Small Cap Fund in June 2019, it advised:

“… it has not been able to grow the funds under management to a sustainable level and does not expect any material growth in the short-medium term … We will commence the realisation of the Fund’s assets, which is consistent with an orderly closure of the Fund.”

The Fund had achieved an impressive annualised return of 24.2% net of fees since inception on 1 August 2016, managed by former Vocus CEO James Spenceley and former Renaissance Asset Management Portfolio Manager, Gary Rollo. MHOR was added to the ASX's mFund service in 2018 to improve investor access, but they gathered only $25 million in total. Clearly, the problem is not simply a performance or access issue.

At CFS, when we assessed portfolio managers wanting to set up a new boutique, we would always check whether they had any major institution willing to back them. Often, these portfolio managers worked at large wealth businesses managing many billions of client capital across multiple portfolios. They developed close relationships with their clients and became friendly with each other. A nod and a wink from a large investor can lead people to believe if they set up on their own, then maybe a $200 million slice could seed a new fund. New boutiques will often offer clients a fee discount to come in at the start, and $200 million at 0.3% is a healthy $600,000 to cover some fixed costs. The test comes when the portfolio manager actually leaves.

When John Sevior departed Perpetual Investments to set up Airlie, many clients went with him. But John Sevior is one of the few ‘rock star’ managers in Australia. If a new boutique cannot deliver immediate institutional support, it can take years of pitching and building up a track record before decent money flows. The retail market is a tough slog full of gatekeepers who must support the new business long before a fund features on a major platform. Research analysts, rating agencies and asset allocators all need convincing.

Going directly to a LIC is difficult for fund managers without a proven track record. Although this looks like direct-to-market distribution, behind the scenes are brokers and financial advisers who are paid fees to support the issue, and they must be convinced there is a story to tell.

7. Misunderstanding the business model

Portfolio managers in large businesses are supported by a phalanx of helpers, from accounting, tech, call centre, compliance, legal, documentation, marketing, business development … on it goes. They can indulge their passion for investing.

Then they set up their own businesses. Suddenly, they become involved in finding premises, negotiating leases, hiring staff, selecting systems to prevent cyber attacks, finding new investors … and all the drudgery of owning a business where the buck stops with the founder. What a pain! Previously, they were Masters of the Universe in a big dealing room, where they blasted the tech guys if the internet went down for 10 minutes. Now the fundies are responsible for making sure their tech is good, and there’s nobody on staff to shout at.

Which is why many talented fund managers sell part of their equity to groups like Pinnacle, Fidante, Channel Capital or Bennelong. In exchange for say 40% ownership, these companies provide support services for boutique managers, leaving them to focus more on investment management. They still need to perform a marketing role but it is done with considerable business development support.

How much does it cost to open the doors? It depends mainly on how much the portfolio managers pay themselves. Remember, many have been highly paid in a previous role and have big mortgages and private school fees to cover, so it’s not easy to take the startup route of no salary for a couple of years. So let’s say they are senior portfolio managers on $500,000 (if that seems too much, consider the salaries of the super fund CIOs listed above, and the CIO of a major retail business can earn $5 million or more a year). Let’s say three other staff cost $500,000, then there are premises, systems, legal, advertising, etc. There’s not much change out of $50,000 to be a major sponsor at a leading industry event. That’s a total of $2 million on the credit card.

Revenues come from clients paying fees. Not only are the big clients pushing down fees, but retail investors can access funds management for free (products such as HostPlus Balanced Indexed Fund - the ‘Scott Pape Fund’ – are effectively free, and the cost of many index ETFs is negligible, less than 0.1%). This new boutique business will need, say, $300 million of institutional money at 0.3% and $300 million of retail money at 0.4% to break even. That is not easy in a market with hundreds of competitors all essentially doing the same thing while striving to sound different.

And the sobering outlook is that for most fund managers, fees are only going in one direction.

8. Inadequate product diversity

Many small fund managers have only one fund based on the skills of one or two people. For the first few years, all their efforts will go into promoting and managing that one fund. It leaves them vulnerable to poor performance and an out-of-favour style. Which is why larger managers branch into income funds, infrastructure, alternatives, ethical or a completely different asset class like an equity manager hiring a fixed interest specialist. The diversity can reduce the business risk.

A comment on relying on performance fees to make a profit. Not only are the fees elusive in a period of underperformance, but such fees are usually structured with a ‘high water mark’. This means the previous underperformance must be recovered before the fee kicks in again. Therefore, a poor year can set back the profitability of the business for many years.

9. Loss of key personnel

Funds management is an industry with massive key person risk. Especially in small boutiques, there are often one or two portfolio managers who have investor support, backed by talented analysts and trainees with little or no market profile or reputation. As funds under management grows, the team increases and resilience builds for long-term survival.

Until this point is reached, however, if the main man or woman wants to leave, the business has nowhere to go. It’s simply not possible to bring in a new person at short notice and expect investors to stay.

The highest-profile demise of all was the closure in 2010 of 452 Capital when Peter Morgan was misdiagnosed with brain cancer. Peter was a doyen of fund managers following his time at Perpetual (Disclosure: I set up the CFS alliance with 452 and was on the Board for a while). At its peak, 452 Capital managed $9 billion, rapidly raising money from 2001. But much of the money exited during Morgan’s time off and with the impact of the GFC, the remaining staff were managing less than $3 billion when the business closed. The Sydney Morning Herald reported:

“Yesterday another high-profile Australian business in this industry, 452 Capital, became the talk of the financial services industry when it was revealed that this business had essentially imploded.”

Fast forward to the recent closures. In 2019, when the AFR reported that Discovery Asset Management was returning funds to its clients, it said the move was driven by the co-founder and Managing Director, Stuart Jordan’s decision to retire. A message to clients said:

"Over the last week, Stuart has cemented his decision to head down the retirement path after a long and successful career in the Australian investment management industry. Given this, and also that Discovery have a small number of institutional clients (only), we have communicated to each of them that Stuart is planning to retire, and we are now working with these institutional clients to 'hand back' or transition out, their mandates with Discovery.”

It is believed that the loss of a mandate from UniSuper contributed to the decision.

A larger ($5 billion under management) and long-established business, Ellerston Capital, closed its Global Macro Fund in June 2019, following the departures of economist Tim Toohey and one of the portfolio managers, Robert Chiu. This was not an under-resourced fund. Former Reserve Bank Governor, Glenn Stevens, was an adviser, with Ellerston announcing on his hire:

"Our main focus is on his international perspective and how other central banks see their economies. He's here to challenge and debate all of our investment theses".

The Head of the Global Macro Fund, Brett Gillespie, is himself a high-profile figure, frequent presenter at conferences and writer of a detailed monthly newsletter on global macro conditions. Yet the loss of key clients took the Fund from $190 million to $30 million and not commercially viable. Returns since inception in 2017 were flat, as shown below.

10. Failure to manage expectations

Every fund manager will underperform at times, but not every fund manager faces large redemptions. Those who emerge into better markets have often spent years explaining their process and when it might not work, and why it will pay off to stay with them.

One manager who has experienced torrid performance in the last year is Steve Johnson’s Forager. A year ago, its LIC was so popular that it was trading at a premium, and his presentations filled conference rooms. The net asset value of the Australian Shares Fund has fallen from $1.82 a year ago to $1.30 now (after a $0.21 distribution). That’s a fall of 19% in a market that is up 12%, a whopping 31% underperformance. Making it worse, the LIC now trades at a discount as some investors have exited, but also as LICs generally have struggled.

Forager has been at pains in the past to stress its investment approach is to buy out-of-favour or unpopular companies, and to ride out the recovery. It has warned that company turnarounds can take longer than expected, and this has been the case. In its recent newsletter, Johnson said:

“Since we started Forager almost 10 years ago, we have told our investors to expect significant periods of underperformance. That’s one promise we have delivered on over the past year ... We have made genuine mistakes over the past year. Part of our poor performance has nothing to do with industry turmoil. But periods of dramatic underperformance like this are not just part of investing with us. They are an essential prerequisite to future outperformance.”

Forager is supported by believers prepared to wait for better days, although it helps that the main fund is a LIC with permanent capital.

Why does this matter to you?

There are three reasons why investors may be adversely impacted by a fund closure, putting aside the impact on the lives of the staff directly affected.

1. Costs of realising the portfolio

Although a small cap manager may not own a substantial portfolio in the overall size of the market, it may be a significant shareholder in some small companies. When it is announced that the funds business will close, the market knows there is a substantial seller of certain companies and the bid price can drop away rapidly. Spreads open. So in addition to other closure costs such as brokerage, the value of the portfolio may fall during liquidation. And, of course, anyone else who owns those stocks will also be hit.

Even where a fund is not closed but transferred to another manager, using a 'transition manager' to sell the old portfolio and buy a new one, the realisation costs can be substantial as most transition managers just want to do the job and move on.

2. Unplanned capital gains or losses

Money is returned unexpectedly to investors, and this might deliver a taxable capital gain or a capital loss which cannot be tax-effectively managed at a convenient time.

3. Lack of access to liquidity while the fund closes

Most fund managers announce their closure and immediately suspend redemptions to prevent a run and to allow for a more orderly share sale process. Investors wanting the capital for other purposes may be denied the expected liquidity.

Briefly, on the other hand …

In case this article paints too glum a picture for fund managers, let’s mention the other extreme, Magellan (ASX:MFG). Its funds under management at 30 June 2019 reached $86 billion, up an extraordinary $4 billion in one month since 31 May 2019. This was mainly due to market movements and the fall in the AUD, but retail inflows were $132 million and institutional $356 million across global, Australian and infrastructure assets. A year earlier, on 30 June 2018, funds totalled $59 billion. That’s up $27 billion in one year.

But here’s the clincher to show how wonderful (or cruel) this business can be for creating wealth. On 2 March 2009, Magellan shares reached a low of 33 cents during the GFC. It recently traded at $55. Ignoring dividends, buying 10,000 shares for $3,300 would now be worth $550,000, only a decade later. Market capitalisation (gulp!): $10 billion.

To offer hope to the strugglers, I remember when Hamish Douglass and Frank Casarotti could gather only a couple of dozen people to Magellan's presentations, and CFS refused to put their global fund onto the main FirstChoice platform.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.