A new report by ANZ and CoreLogic paints a startling and depressing picture of housing affordability in Australia.

Over the 12 months to September 2024, our income growth has again significantly lagged housing and rental growth. Gross household income increased 2.8% to $101,000, trailing the 8.5% rise in the median dwelling value (houses, flats, and other residences) and the 9.6% lift in rents during the period. At the end of September this year, the median dwelling was worth $807,000 and the median weekly rent value was $642 across Australia.

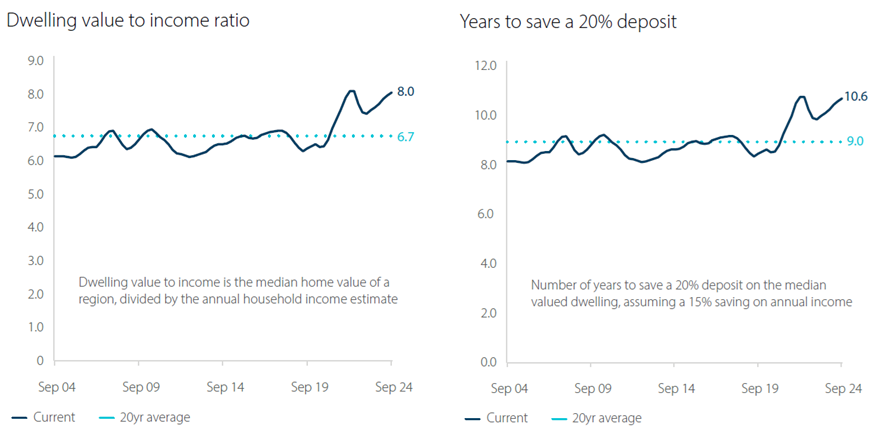

Consequently, housing has become less affordable. The median dwelling value to income ratio has increased to 8x, almost 20% above the average of the past two decades. It’s now caught up to the record highs reached in early 2022.

Assuming an annual savings rate of 15% per annum, it now takes the average household 10.6 years to save a 20% deposit for an average dwelling.

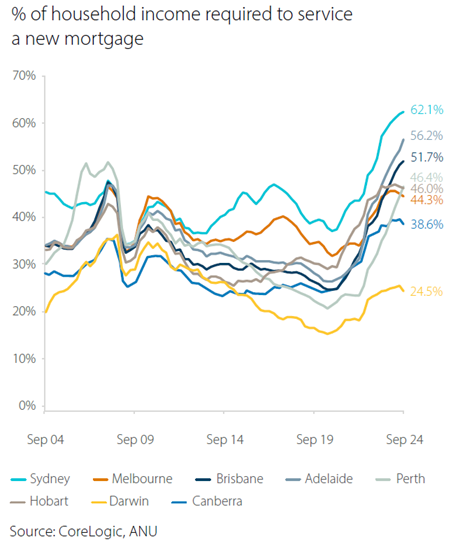

And assuming current mortgage rates for owner occupiers, a 20% deposit and a 25-year loan term, more than half of the median household income is needed to service a new home loan.

The report acknowledges that its focus on savings and income neglects other means of accessing the housing market such as selling a home already owned, using the Bank of Mum and Dad, access to Government schemes such as the First Home Guarantee, buying a cheaper home than your income would suggest you can, and so on.

However, it says that these alternative measures may be the reality for some, though not all. That’s why it’s important to assess housing values against incomes to benchmark housing affordability.

An extraordinary picture of housing affordability

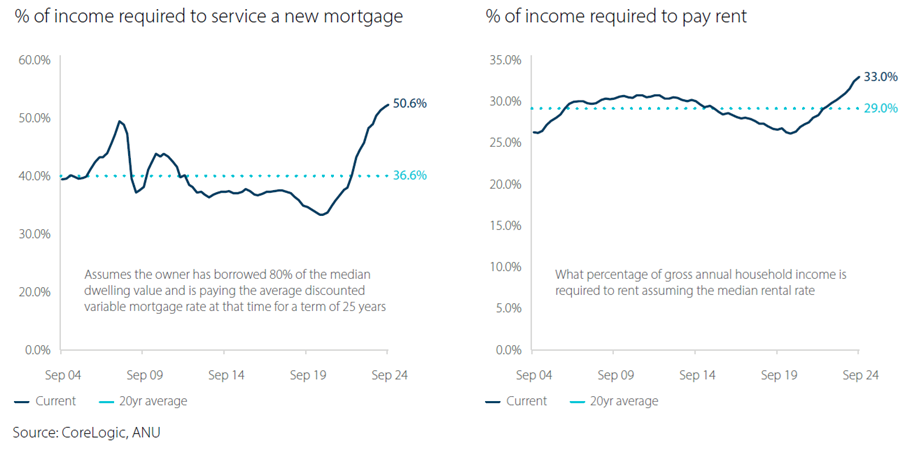

The report’s breakdown of housing affordability is eye-catching. It reveals only 10% of the housing market is genuinely affordable – require less than 30% of income to service a loan – for the median income household. That’s down from the 40% figure recorded just two-and-a-half years ago.

For low-income earners, the affordability figure drops to 0%. And even for the 75th percentile income household, with gross income of $172,00o per annum, only 50% can afford to service a current loan.

Are apartments set to outpace houses?

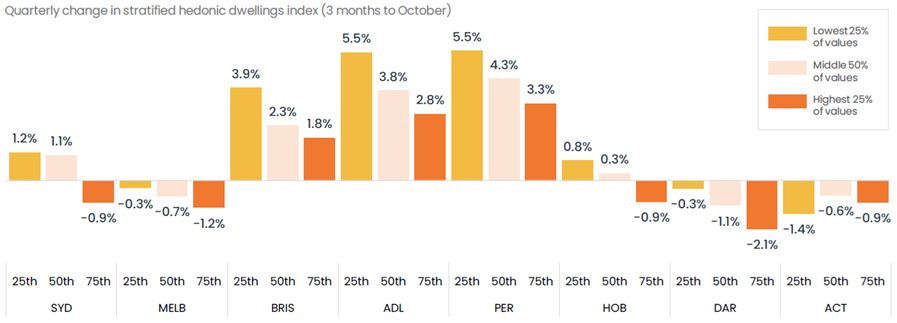

The authors note that less affordable housing may be shifting demand towards units over houses. In the three months to October, capital city unit prices rose 0.9% compared to the 0.8% increase in houses. A chart from another CoreLogic paper shows this trend most clearly.

Source: CoreLogic

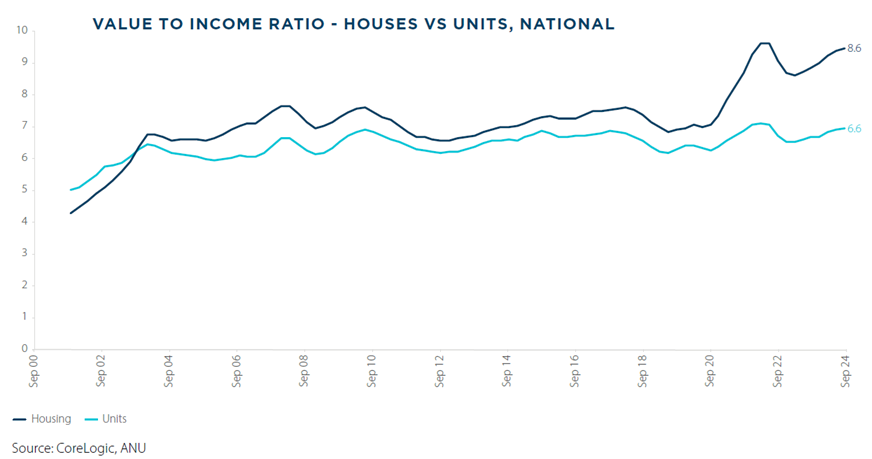

The growth in unit versus housing values may not seem much yet they’re quite a turnaround from recent trends. Between March 2020 and October 2024, national housing values grew 44.5%, more than twice the rate of increase in units, at 20.7%.

Over the same period, the difference between the median house and unit value across Australia increased from $46,000 to $207,000. At September 2024, the portion of income needed to service a mortgage on a median value house was 55% versus the 42% for units.

Moreover, the dwelling value to income ratio for houses has almost doubled to 8.6x over the past 23 years, while the same ratio for units has only increased 32% to 6.6x.

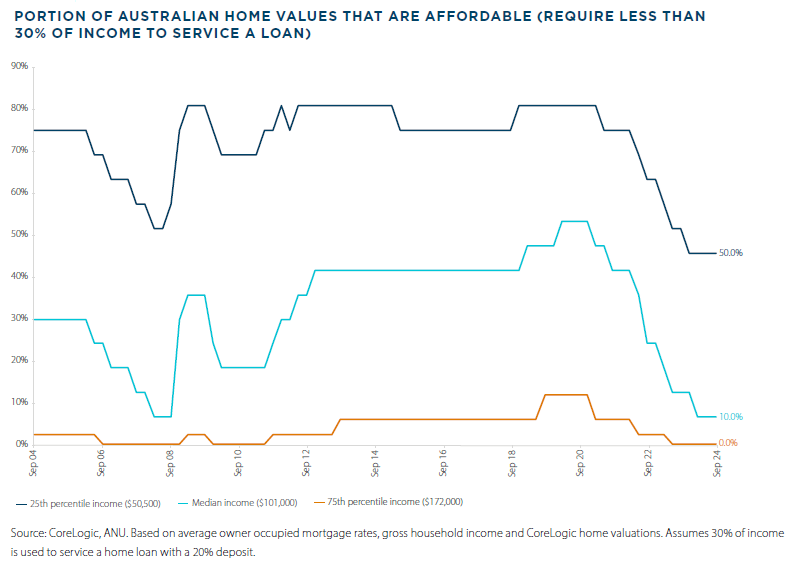

Comparing affordability across cities

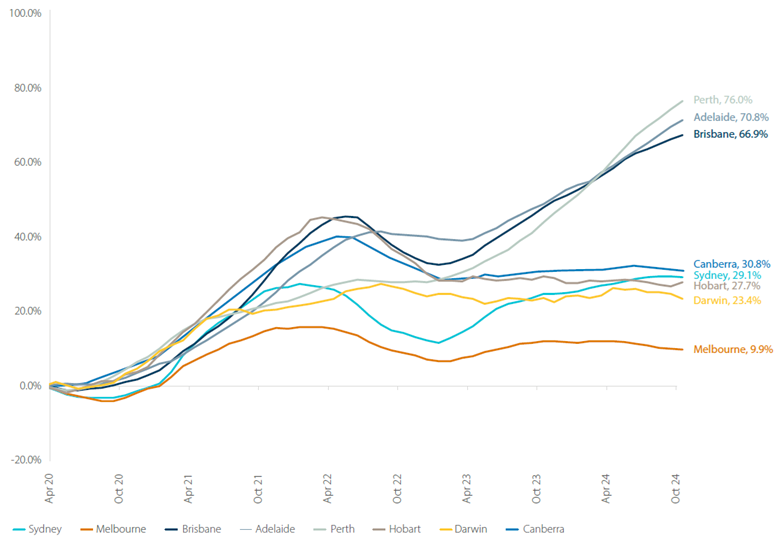

Affordability across the capital cities has changed dramatically since Covid. In the 4.5 years to October this year, the housing prices of three cities have rocketed, leaving the rest far behind. Perth, Adelaide, and Brisbane dwellings rose 76%, 71% and 67% respectively.

Meanwhile, the other cities haven’t done much, especially if you take inflation into consideration. Canberra, Sydney, Hobart and Darwin are up 23-31%, while Melbourne is only 10% higher (and down significantly in real terms).

Cumulative change in dwelling values since March 2020, capital city markets

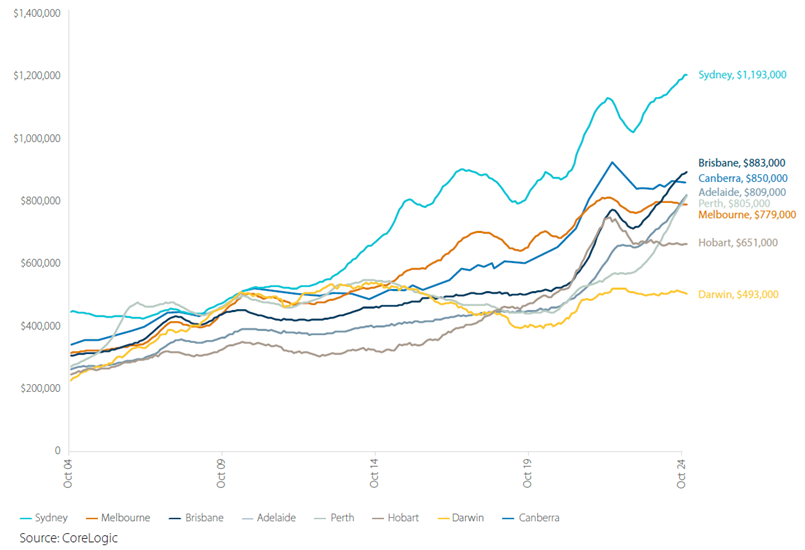

Median dwelling values

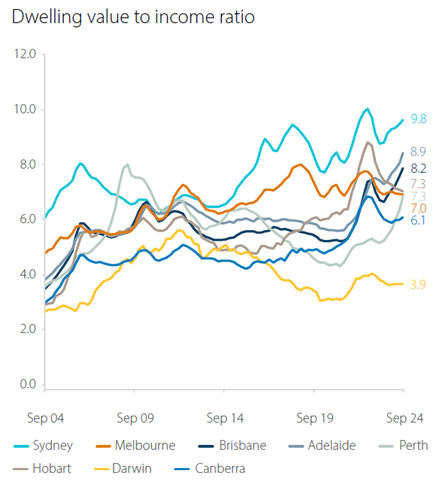

Adelaide has seen the largest deterioration in housing affordability. The median dwelling value to income ratio has risen from 5.9x in April 2020 to 8.9x now. That makes the city the second-least affordable capital city, with 56% of income needed to service a new mortgage and almost 12 years to save a 20% deposit.

It’s also harder to afford a home in Brisbane and Perth too. Brisbane is now the third least affordable city, with 52% of household income required to service a new mortgage.

Despite Sydney homes growing less than some of the smaller cities, it remains the least affordable capital city in Australia, with a dwelling value to median income ratio of 9.8x.

Meanwhile, Melbourne has become much more affordable thanks to a gloomy economy and a government mired in debt.

Will housing affordability improve next year?

The report notes that demand for housing has softened in recent months, with higher interest rates, cost of living pressures and elevated home values deterring buyers. And in some cities, such as Sydney and Melbourne, house values have started to fall.

Then it says:

“Cyclical downturns often do not lead to long-term improvements in housing affordability, because the declines eventually attract new buyers in the market.”

This seems a little naïve and based on evidence from the extraordinary housing boom over the past 40 years ie. recency bias. A broader sweep of history shows that cyclical downturns can certainly make housing more affordable, and it can take a long time before buyers step in to buy the dips.

The report goes on to suggest that affordability may improve with rate cuts ahead. ANZ forecasts 75bps of easing, starting in February next year. Assuming no change in incomes, and no upward pressure on housing values, that would reduce the national metric of income needed for a new loan from 51% to 47%.

Yet, the data in the report suggests that it’s going to need a lot more than lower rates for most Australians to be able to afford a home any time soon.

James Gruber is Editor at Firstlinks.