Why are interest rates so low? Ask this question to the man-on-the-street and they will likely tell you that the economy is struggling, and the world is facing great uncertainty.

Yet ask an equity analyst about low rates and many will tell you that they are great for asset prices and can propel equity markets even higher in 2020.

Unsurprisingly, there seems to be a disconnect here. Companies rely on the economies in which they operate to drive growth, and if global growth is low, the earnings outlook will be challenged.

So who is right about the outlook for 2020 and beyond? In my opinion, the common sense of the man-on-the-street may be closer to the mark than many professional investors. Growth prospects are low and uncertainty is high, which is not a great combination for many companies.

Some equity market investors are falling into the trap of thinking that interest rates are low purely for their benefit. We believe this is at the heart of why investors get their company valuations wrong.

Why is this wrong?

An investor's job can be simplified to two primary tasks.

First, to predict what a company's cash flows or earnings will be in the future.

Second, to work out how much to pay for those earnings.

In our valuations, we link nominal GDP growth, which is the key driver of earnings, with nominal risk-free rates, which is the key driver of multiples or discount rates. If you lower the discount rate (because bond yields and rates are so low) but maintain trend earnings, it is mathematically possible to justify some of the multiples we are seeing in global equities.

However, at some point, we believe there will be a reckoning. Either earnings are going to disappoint (because growth is lower) or over time, rates must rise. Either way, this will be painful process for the share price of many companies, particularly overvalued companies.

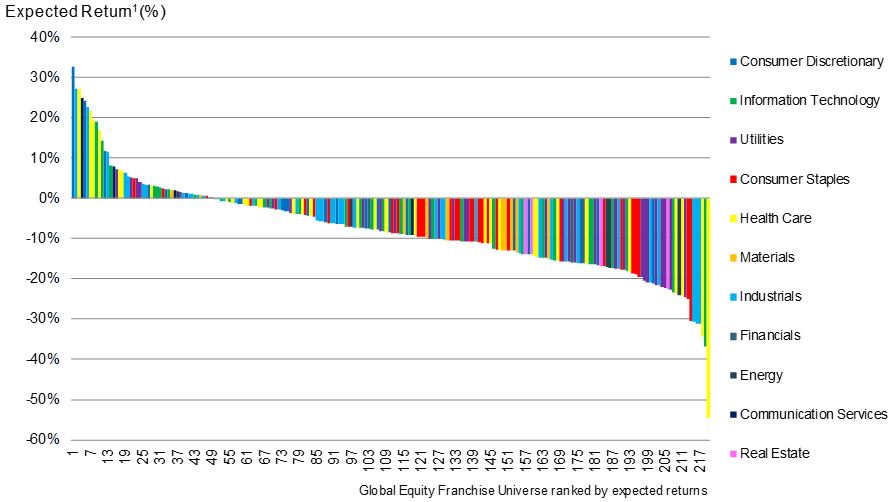

Exhibit 1 is a universe of 250 of the world’s highest quality global companies (based on criteria we use to identify businesses with strong economic moats and predictable earnings), as at 30 September 2019. We have ranked them according to their potential upside, with reference to the differential between their ascribed ‘intrinsic value’ as determined by our fundamental analysis, and the current prevailing market price.

Exhibit 1 shows there is a relatively small number of stocks that will produce strong expected returns over three years, assuming shares trade at our valuation in three years’ time (above zero are companies with positive expected returns, below the line are negative expected returns). Worryingly, for less valuation-sensitive investors, we are ascribing large negative expected returns for many companies (the right-hand side of chart). The lesson here is that buying generally highly regarded companies can lose you money if brought on the wrong valuation.

Exhibit 1: A high quality universe of global shares, value ranked by sector

The opinions and estimates contained in this graph are based on current information and are subject to change. It should not be assumed that any investment was, or will be, profitable. Expected returns do not represent a promise or guarantee of future results and are subject to change. Shown for illustrative purposes only. Currency: AUD.

Each bar represents an individual stock’s expected return per annum for the next three years. This is based on a comparison of Lazard's Global Equity Franchise team’s intrinsic valuation of the stock three years out, the market price of the stock today and the interim forecast dividends.

The largest and most expensive stocks have fared the best

Many of the world-leading companies in the above chart have driven the bull market in 2019. While we acknowledge that some of these technology stocks, in particular, are high-quality businesses with powerful competitive positions, many of them are now trading on multiples that we cannot justify.

The outperformance by the largest stocks in the market is unusual in an historical context. The largest 40 stocks by market cap globally have outperformed recently. This is a reversal of the historical trend where these mega caps normally underperform the broader market.

Related to this has been that the most expensive stocks have also outperformed less expensive stocks, consistent with a momentum driven market.

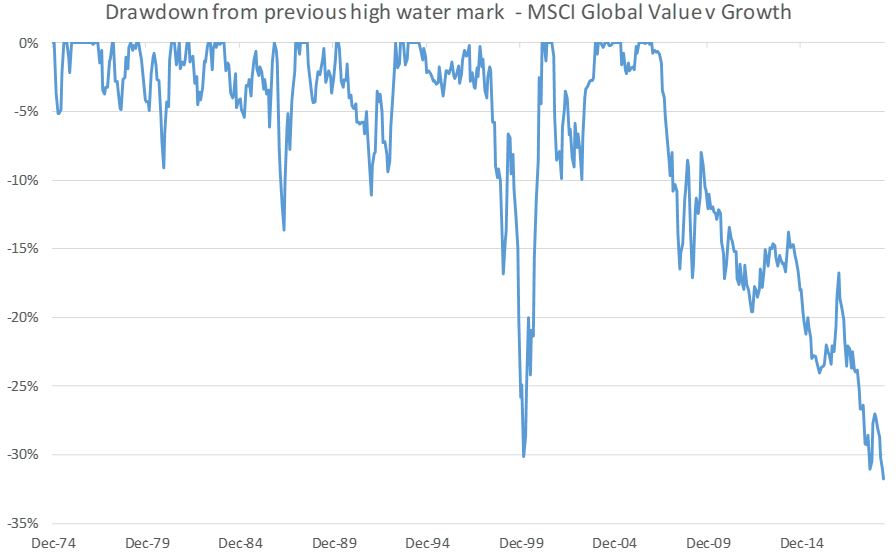

This has meant that the value drawdown versus growth has now exceeded the 1999 low, making it the biggest drawdown (relative loss) for value stocks in over 30 years, as shown in Exhibit 2. Our view is that this will likely return to an equilibrium level that is more consistent with what we have seen through history. This reversion has historically proven a powerful tailwind for valuation focused investors.

Exhibit 2: Ratio of total returns on value versus growth breaches low point

Shows the ratio between the total returns of the MSCI World Value Index and the MSCI World Growth Index. Source: MSCI

Pockets of opportunity

We are confident that value investors will receive some reward for their discipline as we enter a late cycle period. History shows that when these cycles reverse, they can do so aggressively.

Even in this expensive market, we are seeing some value opportunities. From a global point of view, we are seeking high-quality business that are facing some short-term issues, which for us is creating the value opportunity.

In this category, we would include leading marketing data collection and analytics firm Nielsen, lottery concession holder IGT and tax firm H&R Block. These companies may not be household names, but what they do share is a dominance within their given market and a strong economic moat.

In Australia, we see some value in quality resources companies with growth potential, including Rio Tinto and Woodside. The Lazard Australian Equity team also favours some domestic infrastructure securities for their defensive earnings including Transurban and some growth stocks that have fallen out of favour, such as Domino’s Pizza.

In our view, passive indices and some active portfolios with a mega cap or growth bias will be challenged by a market that is focused more on fundamental valuation and less on momentum drivers. We also believe it is a mistake to use low rates to boost earnings multiples if you do not reduce growth expectations. These two numbers (interest rates and growth) must remain connected for a robust valuation framework.

Relative to fixed income and cash, equities can still make sense in 2020, but investors must be disciplined in their valuation frameworks and not overpay, particularly this late in the cycle.

Warryn Robertson is a Portfolio Manager/Analyst on the Lazard Global Equity Franchise, Global Listed Infrastructure and Australian Equity teams. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.