The post-lockdown resurgence of the Australian economy between 2021 and 2023 brought with it a confluence of inflation-inducing effects.

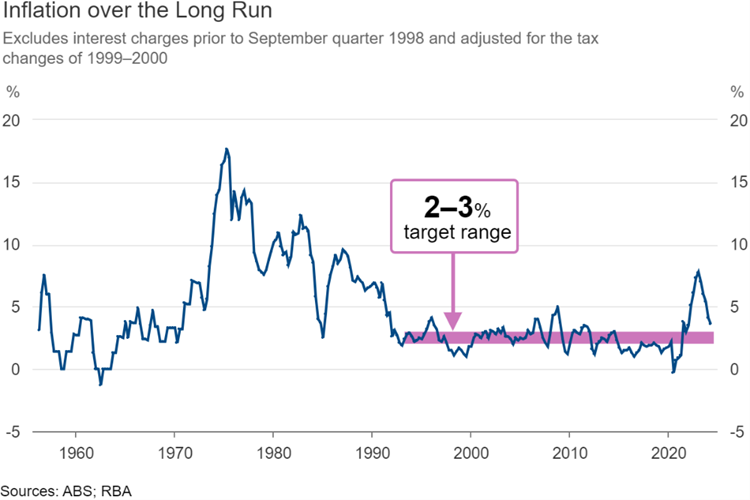

Consumer inflation, as measure by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), started to trend up in early 2021, rose past the RBA’s target band of 2% – 3% p.a. by mid-year, and would go on to register an astonishing 7.8% for calendar year 2022.

The RBA responded to the inflationary threat by lifting interest rates 13 times between May 2022 and November 2023, resulting in the current cash rate of 4.35%.

If CPI is used as a measure of inflation policy success, this intervention appears to have worked, with the latest CPI coming in at 3.6% year-on-year for the March 2024 quarter, almost back within the RBA’s target band, as the below chart indicates.

But what if CPI isn’t the most appropriate measure of how Australians actually experience cost-of-living pressures, given their personal consumption patterns?

CPI – a blunt measure of cost-of-living

The CPI has been measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) using the same basic methodology back to at least 1960.

It aims to measure changes in the price of a fixed quantity (basket) of goods and services acquired by consumers in metropolitan private households (what the ABS terms 'the CPI population group').

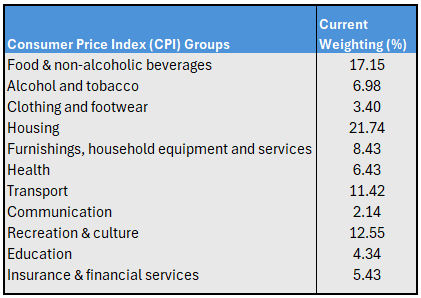

Prices are tracked across thousands of items that are aggregated into one of 11 groups, these being:

Source: ABS, Consumer Price Index, Weighting Pattern, 2024

The weightings in the CPI basket above are meant to be representative of the consumption pattern of the ‘typical’ Australian household.

Except it’s a big ask for one basket of good and services to accurately reflect the consumption preferences of disparate households that may differ by geography, age, income and, importantly for retirees, connection to work (sources of income).

In truth the CPI is not a measure of the changing purchasing power of households with differing consumption patterns. The ABS itself concedes the point, noting that :

“At the end of the day, the CPI is most useful as an indicator of price movements, whether it be for specific items, a particular city, or the economy as a whole. The CPI is not a precise measure of individual household price experiences.”

Thankfully, the ABS has other inflation gauges that are better at assessing cost-of-living changes across differing household types.

Selected Living Cost Indices

To overcome the known limitations of the CPI in measuring household purchasing power, the ABS progressively introduced a series of Living Cost Indexes from 2000 onwards.

Whereas the CPI measures the change in price of a fixed basket of good and services, these cost-of-living indexes measure the change in the minimum expenditure needed to maintain a certain standard of living.

The ABS publishes four distinct ‘Analytical Living Cost Indexes’ (ALCIs) based on household type that, in aggregate, account for 90% of Australian households, these being:

- employee households (income principally from wages and salaries);

- age pensioner households (income principally from the age pension or veterans affairs pension);

- other government transfer recipient households (income principally from a government pension or benefit other than the age pension or veterans affairs pension); and

- self-funded retiree households (income principally from superannuation or property, and where the defined reference person is ‘retired’).

In addition, a Pensioner and Beneficiary Living Cost Index (PBLCI) is also maintained, this index effectively blending the middle two above, to cover households whose principal source of income is from government pensions and benefits.

According to the ABS, these five indexes are “specifically designed to measure changes in living costs for selected population sub-groups and are particularly suited for assessing whether or not the disposable incomes of households have kept pace with price changes”.

How do LCIs track cost-of-living changes?

The CPI and LCIs share the same overall design and calculation methodology, both tracking price changes across the same 11 groups.

The key difference between the two relates to the cost of housing. The LCIs include interest charges on mortgages but exclude new house purchases. The CPI includes the cost of new house purchases (i.e. new builds) but does not include interest charges on mortgages.

That, as it turns out, causes the CPI and LCIs to diverge in dynamic interest rate environments (as was the case between mid-2022 and the end of 2023).

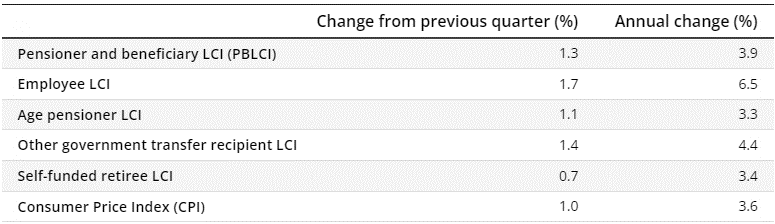

While headline CPI rose 3.6% for the year to 31 March 2024, the equivalent household inflation for the different household types is provided in the table below.

Source: ABS, Selected Living Cost Indexes, Australia (March 2024)

Self-funded retiree households experienced an increase in their cost-of-living, but slightly below the headline CPI rate, as did age pensioner households.

Other government transfer recipient households (typically of working age) and employee households fared worse than CPI, with the latter seeing their cost-of-living surpass CPI by 2.9 percentage points over the year.

The main driver of this divergence has been interest charges. The current weighting for this expenditure is almost 12.5% for employee households, as compared to just over 1% for self-funded retiree households and 1.6% for age pensioner households.

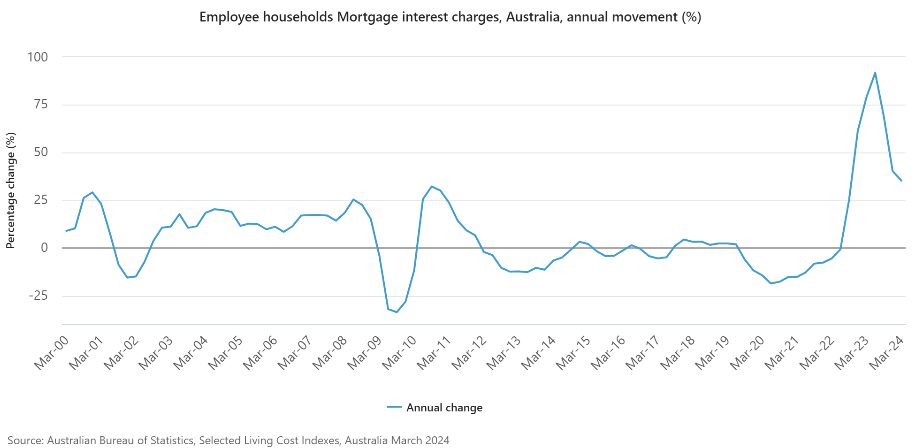

Source: ABS, Selected Living Cost Indexes, Australia (March 2024)

With mortgage interest charges rising 35.3% during the past year (easing from a peak of 91.6% during the June 2023 quarter compared to a year earlier), the current cost-of-living crisis for many home-owning Australians, particularly those in their thirties and forties, could perhaps be better described as a ‘cost-of-mortgage crisis’.

Current sources of cost-of-living stress for retirees

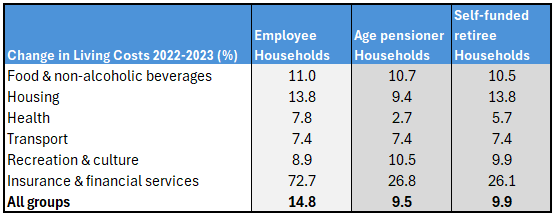

Below is a selection of spending categories from the age pensioner and self-funded retiree LCIs, displaying the percentage change in index values over two years, from the start of 2022 to the end of 2023.

Employee households are included, indicating how working-age households have fared in comparison to retiree households.

Source: ABS, Selected Living Cost Indexes, Australia (March 2024, Table 2)

The two retiree groups within the LCI may have had broadly similar overall cost-of-living experiences over the past two years, but with distinct differences across specific expenditure items.

The main ones being insurance premiums and mortgage interest charges.

Self-funded retiree households tend to hold more, and higher premium, insurance products. Insurance premiums have soared across house, home and contents, landlord and motor vehicle insurance over the past year, some at the highest rates since the LCIs were first introduced.

Age pensioner households, by contrast, have been more impacted by the sharp rise in interest charges since mid-2022, particularly those still servicing mortgages, but also credit cards and personal loans.

Should CPI be used in retirement planning?

Inflation is central to any conversation on retirement, because its pernicious effects erode purchasing power over time and, with it, one’s standard of living.

So central is inflation risk to retirement that it makes its presence felt right across the superannuation sector, from investment return objective setting (CPI plus targets) to retirement income forecasting (inflation-adjusting projected balances for ‘today’s dollars’).

The Retirement Income Covenant, a requirement for all APRA-regulated super funds since July 2022, also explicitly names inflation as one of three key risks that members face in retirement, and that trustees must address in building retirement solutions.

But it’s patently clear that the CPI is not best placed to be a measure of inflation as experienced by households, especially once in retirement.

A lot of that is due to the CPI no longer measuring mortgage interest charges.

Some 14% of homeowners aged 65 and above now still carry a mortgage. Australians may therefore increasingly be subject to mortgage rate shocks, of the kind experienced during 2022 and 2023, well into retirement.

Add to that the sharp rises in private market rental over the past 12 months and, for the 18% of those over 70 who don’t own the roof over their heads, rent inflation can impact far more than its weighting in the CPI might indicate.

The changing, increasingly tenuous, nature of housing in retirement therefore warrants a rethink of CPI as the best measure of retiree cost-of-living pressures.

In fact, the base rate of Age Pension (itself indexed to Male Total Average Weekly Earnings) already indexes its half-yearly increases to the higher of CPI and the PBLCI.

A case can therefore be made for self-funded retiree and age pensioner retiree households to have the relevant ABS living-cost-indexes applied to their circumstances in other areas, such as inflation indexation for retirement income products.

As the saying goes: ‘what gets measured gets managed’.

With the CPI we’re not measuring what truly counts in retirement; maintaining a dignified standard of living irrespective of the specific cost-of-living pressures we may encounter along the way.

Harry Chemay has over 26 years of experience in both wealth management and institutional asset consulting. Initially a private client adviser with an SMSF focus, he has since consulted across wealth management, FinTech and superannuation, with a focus on improving post-retirement outcomes.