The coordinated global fall in interest rates since the 2008 financial crisis has been one of the greatest tailwinds to asset prices in modern financial history. Interest rates underpin the valuation of most financial assets as their expected future cash flows are discounted relative to government bond yields. The effect of falling discount rates has been to increase their present capital values (i.e. their prices).

This dynamic has become progressively more extreme as the accumulated effect of extraordinary central bank intervention - abnormally low interest rates, combined with asset purchases - has pushed government bond yields to historically low (or even negative) levels and propelled investors to ever greater heights of risk-seeking behavior.

Is the party finally over?

This tailwind is subsiding. While the stronger global economic growth and declining central bank policy stimulus narrative is becoming more widespread, the missing chapter of the story has been inflation, which has been slow to emerge.

Not only is low inflation pervasive today, it has also become stubbornly entrenched into inflation expectations far into the future as markets assume the party continues along with very gradual policy normalisation.

However, given this policy normalisation is occurring after an unprecedented period of market-distorting stimulus, it is far from clear what the unintended consequences will be for financial markets. Even a little unexpected inflation can easily upset this delicate balance.

There are early indications that inflationary pressures are building. Notably, labour markets globally are tightening, manufacturing costs are rising and even in the land of deflation, the Bank of Japan recently noted that inflation expectations have stopped falling.

For years, central banks have prolonged stimulus without any real knowledge whether inflation transmission is working, thereby risking an overshoot. History shows that when inflation expectations shift, they shift quickly, which could force more aggressive policy normalisation than markets are expecting.

In this scenario, the party may be over.

What does this mean for investments?

Assets that shone brightly against the dim light of a low interest rate world would be reassessed under the harsh glare of higher interest rates. Against this backdrop, it’s natural to question whether government bond holdings can still play their traditional role as risk diversifiers.

Let’s begin with the traditional context, where a conventional ‘risk-off’ scenario like a recession occurs. Investors can probably expect their government bond holdings to help offset equity losses as capital flees to safety and bond prices rise as interest rates are cut.

Alternatively, if the current consensus view – improving growth, contained inflation and gradually rising rates – does play out, bonds provide stable income but still expose investors to risk of modest capital losses from rising interest rates (duration risk).

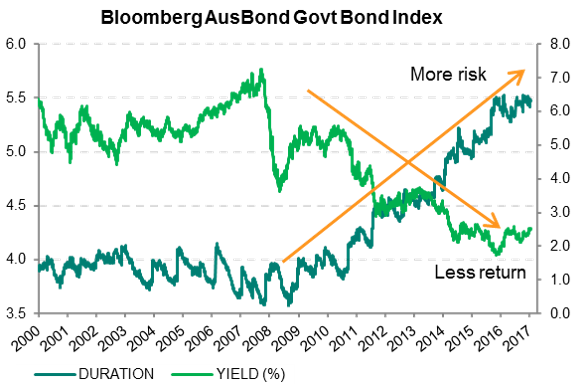

The current combination of very low yields and term premia (compensation for holding long maturity bonds over shorter bonds) means bond holders are being poorly compensated for bearing duration risk as a form of risk diversification. The issue is compounded for passive bond investments as benchmark index duration has extended (taking more risk), while average yields have declined (less return) creating an asymmetric risk of capital losses from rising interest rates.

Source: Ardea, Bloomberg

Even in the scenarios where bonds perform as intended, it is expensive to passively hold them at present for risk diversification.

But it could be worse

The underestimated scenario – nascent inflationary pressures become more established – would quickly shift focus to fear of inflation overshooting, forcing aggressive, unexpected and disruptive normalisation of monetary policy. Bonds then become the catalyst for a broader asset class sell-off, rather than acting as a defensive risk diversifier.

We got a small taste of what such unanticipated policy tightening can do to markets during the ‘taper tantrum’ in 2013. Ben Bernanke unexpectedly announced the possibility of reducing the US Federal Reserve’s bond buying programme, causing bond prices to drop sharply and triggering a sell-off in equities. The chart below shows how the Australian bond-equity correlation behaved before and after this event – becoming more positive, more often, and thus less reliable as a diversifying relationship.

ASX 200 vs. AU Govt. Bond Correlation

Source: Ardea, Bloomberg

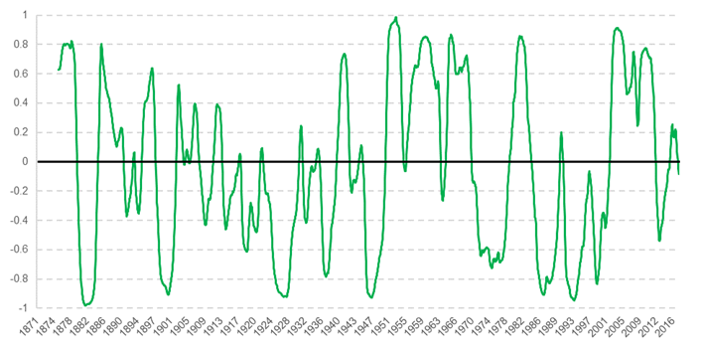

In fact, this marked change is not unique to Australia or to recent history. Very long-term US data shows that bond-equity correlations are unstable, tending to be impacted by inflation and interest rate paradigm shifts.

5-year rolling bond yield - equity correlation (daily returns)

Source: Ardea, Shiller, R. Source data for Irrational Exuberance, 1871 to present.

Irrespective of whether we are in a paradigm shift in bond-equity correlations or not, the conclusion remains the same. The assumed negative correlation between bonds and equities is not as reliable as hoped for.

The implication for portfolio construction is clear. Investors should evaluate conventional assumption that passively owning government bonds is inherently defensive and risk diversifying.

More to fixed income than buy and hold

There’s more to fixed income than just buying and holding bonds. It is an asset class with a wide range of instruments, strategies and return sources that can be exploited to achieve genuine risk diversification. For example, the same factors that distorted bond market valuations have also created relative value pricing anomalies, underpriced volatility, skewed risk premia and offered cheap tail risk opportunities that can all be used for effective risk diversification in a truly defensive fixed income portfolio.

So yes, fixed income can still diversify portfolio risk but only if you choose the right strategy.

Gopi Karunakaran is a Portfolio Manager at Ardea Investment Management, a boutique fund manager in alliance with Fidante Partners. Fidante is a sponsor of Cuffelinks. The information in this article is general in nature and is not intended to constitute advice or a securities recommendation.