The Financial System Inquiry (FSI) makes some important recommendations which would improve the industry if implemented. I agree with the recommendation to clearly define the objectives of superannuation, against which government policy and super fund activities would be assessed. Some of the language used such as “consumption smoothing” (the acknowledgment that the intention of super is to force us to save out of current earnings to provide for consumption when we are no longer earning wages) deserves credit for the way it can re-focus an industry. However the elephant in the room, the trade-off between return and risk, is largely left untouched. This lack of guidance was an important opportunity missed in the FSI.

The trade-off between return and risk is an age long topic. My reflections first address the accumulation focus of the industry and then I consider a retirement outcomes focus.

Risk versus return in accumulation phase

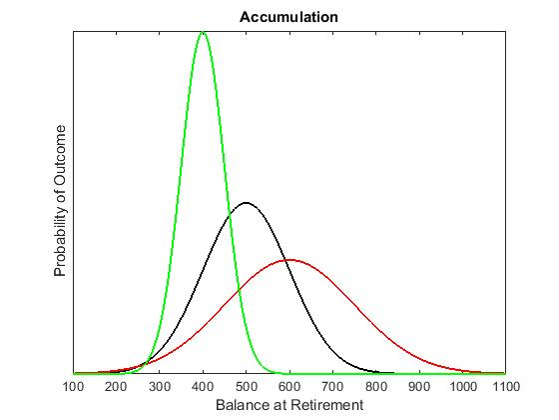

Until recent years much of the industry focus has been on superannuation balances at retirement. “How big will your nest egg be?” was a common phrase between industry and consumers. Trustees of super funds had to define the appropriate trade off between return and risk for the default members in their funds. The decision facing the trustee is illustrated in the diagram below.

The above diagram is an illustration of the distribution of outcomes of a member’s balance at retirement once we account for expected contributions and performance. The black line represents the base case. A trustee could take more risk on the member’s behalf. Represented by the red line we expect the accumulation at retirement to be higher (assuming that a higher risk portfolio is expected to deliver higher returns). But the range of potential outcomes is wider, and some of the potential outcomes may be unpalatable. Conversely a trustee could reduce risk, as represented by the green line. The range of potential outcomes is narrower, representing more certainty, but (assuming that lower risk equates to lower expected returns) the expected size of the nest egg at retirement is reduced. Certainty and level of expected outcome pull against each other – yet both are desirable. Note the above analysis could be presented in real or nominal dollars, with real dollars the more appropriate approach.

This is broadly how the ‘70/30’ default portfolio evolved (70% growth assets such as shares and 30% defensive assets such as bonds), however I haven’t seen much compelling historical research that explains the origins of ‘70/30’. Indeed there is a possibility that ‘70/30’ was just back of the envelope analysis that took on an inertia-driven life of its own via peer group risk!

Risk versus return in retirement phase

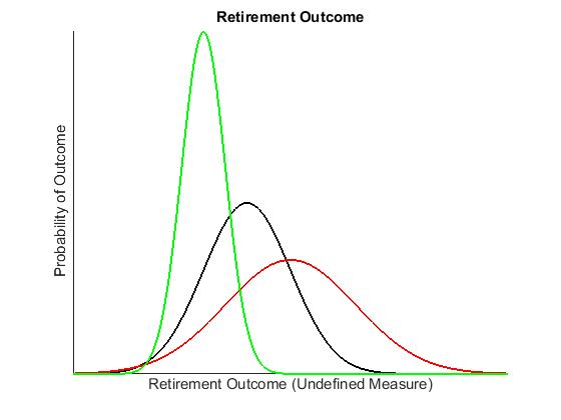

Let’s now switch to the more recent focus on retirement outcomes. The same problem remains but it is more complex and detailed. And again the same ambiguity about the correct trade-off between expected outcome and variability of outcome exists. The diagram below looks similar but the subtle differences are important.

Notice the emphasis on the words ‘retirement outcome’. This is a complex topic: how do we define retirement outcome? I suggest it should include the following (but weighting these factors would be complex):

- the level of retirement income

- whether it is achieved through the entire retirement period (does it drop off or run out?)

- the liquidity that is available to meet possible life events (such as a retirement home bond)

- any bequest motive (though this is debateable and likely a secondary issue).

Given the definition of outcome is more complex it is not hard to imagine that measuring the variability of the outcome is also a more intricate exercise. Nonetheless the same framework is relevant: a trustee can make decisions which exchange the level of expected outcome for the opposite move in the variability of the outcome. Both are desirable, and indeed certainty of outcome should be valued and some people view certainty as a luxury. The projected outcome should be considered in terms of the expected outcome against the variability of the projected outcome.

FSI recommendations made without guidance on this trade-off

Alas what remains undefined and unguided by policymakers is the appropriate trade-off between expected outcome and variability of outcome. Every regulatory review, including the FSI, represents an opportunity to address the elephant in the room.

Without such guidance some of the recommendations made in the FSI appear somewhat less formed. Consider two important recommendations made: improving cost efficiency and developing a comprehensive income product for members’ retirement (CIPR) which addresses longevity risk. Let’s consider these in the outcome framework just outlined.

Cost reductions could increase net investment returns (if achieved through efficiency gains and the deletion of non-beneficial functions and services), or reduce net returns if it means more passive management for a fund that can add value through active management. Cost reductions may increase return volatility because less diversification opportunities into areas such as alternative investments will be available. So all up, a cost reduction focus may increase or may decrease net returns but will likely increase the volatility of returns. So at best this recommendation appears to be pulling the outcome in opposite directions – higher expected outcomes (assuming the FSI believes lower costs translate to higher returns and that active returns don’t exist) but greater variability of outcomes. In the absence of direction as to the appropriate trade-off between expected outcomes and variability of outcomes it is unclear whether such a recommendation will actually improve member outcomes or not.

What about all those other types of risk?

The FSI also recommends the creation of a CIPR to address longevity risk. On the surface, this is a worthwhile recommendation. However longevity risk is just one of many risks to retirement outcomes – investment returns, return volatility, inflation rates, wage growth, house prices, savings rates, mortality outcomes, age pension and taxes, just to name a few. There would be different costs (a negative impact on returns) in hedging these different risks. Perhaps it is cheaper to hedge a unit of investment risk than a unit of mortality risk. If so, then from an outcomes perspective it could be better to hedge a unit of investment risk before we hedge the mortality risk. It is also unclear which risk is most significant to retirement outcomes. What the FSI has done is paternally recommended that we prioritise the hedging of one risk over another, with little assessment of the cost of hedging the different forms of risk or the size of those risks. All this is in the absence of guidance as to the appropriate trade-off between expected outcome and variability of outcomes!

While product solutions such as the CIPR often appear the solution and can really define a regulatory review, it may have been more beneficial to recommend that funds develop more detailed processes and capabilities for modelling what retirement outcomes will look like. It would have been wonderful if a review addressed the elephant in the room, the appropriate trade-off between return and risk, including different types of risk.

David Bell is Chief Investment Officer at AUSCOAL Super. He is working towards a PhD at University of New South Wales. The views contained in this article are those of the author and not AUSCOAL Super.