The Australian housing market has steadily reaccelerated since the middle of this year. House prices across most capital cities had been falling for 21 consecutive months, but finally bottomed out in around May 2019 and are now rising again.

Just last month, house prices rose at their fastest rate in more than four years and have already regained a third of the past two years’ losses.

There are three main contributing factors to the recent turnaround:

First, the RBA has cut interest rates three times since May, lowering the cost of borrowing for households.

Second, the coalition government’s success at the Federal election in May removed some of the perceived risks to the capital gains discount and negative gearing, locking in these favourable housing policies for investors.

Third, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) reduced the interest rate serviceability measure that banks are required to use when assessing home loan applications. This relaxation of lending standards led to an increase in successful applications.

Ultimately, these factors have all contributed to more buyers entering the national property market, however the number of new listings of properties for sale is much lower than a year ago and this is compounding price increases.

Capital city prices recover quickly

Whilst overall the outlook is positive for property investors, the turnaround is not consistent across the country. Around 40% of Australia’s population lives in Sydney and Melbourne and price rises there have been much higher than in the rest of Australia.

Residential property prices have increased by around 5% in Sydney since May, and in Melbourne by around 6%. That’s a significantly steep jump in just a few months. Gains in Brisbane have been about 1.1% in the three months to October, while Adelaide’s movement is minimal. Perth remains out of sync with the rest of the country and house prices are still falling, down more than 21% since their peak.

It’s not unusual that house prices in Sydney and Melbourne have bounced back more strongly. The population in both cities continues to grow (2.1% in Melbourne and 1.6% in Sydney), and despite healthy home construction rates over the last few years, there’s still an issue of undersupply.

According to CoreLogic, we can expect to see prices accelerate even further next year, with Melbourne hitting a new peak as early as January, Sydney in the first half of the year and Brisbane is on track to recover to previous highs. The smaller housing markets in Canberra and Hobart have already reached new record levels.

We anticipate that residential property prices will rise another 5% after this initial bounce has run its course.

Implications for macroprudential policy

Monetary and fiscal policy are the two main levers used by policymakers to influence the economy. But, macroprudential policy has also been gaining popularity as an additional policy tool to offset some of the risks created by low interest rates.

Macroprudential policy deals with managing financial stability risks which usually means limiting credit and debt growth, tightening lending standards and increasing bank regulation.

In Australia, APRA is in charge of administering macroprudential regulation, with the RBA also involved in consultations. From 2013 to 2016, interest rate cuts and housing undersupply (predominately in New South Wales and Victoria) fuelled rapid home price growth. The regulators were concerned about the huge lift in investor lending and the sharp rise in interest only loans. From late 2014 onwards, APRA introduced various macroprudential tools to combat these risks in the housing market including:

- limiting banks’ investor loan growth

- introducing a minimum 7% interest rate when assessing new loan serviceability

- greater scrutiny on loan applicants expenditure based on average household expenditure and overall debt levels

- increasing capital buffer requirements for banks and limiting interest-only lending.

The progressive use and tightening of macroprudential policy over 2014-2017 was a significant contributing factor behind the slowing in housing prices and credit growth, especially for investors.

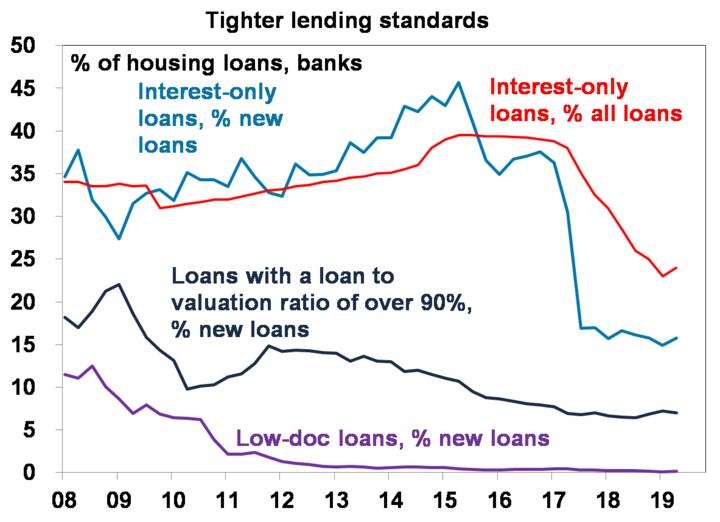

Macroprudential tightening significantly reduced the proportion of ‘risky’ interest only loans which fell from around 40% of total loans at their peak in 2015 to around 24%, as shown below.

Source: ABS, AMP Capital

In 2017, APRA started to remove some of the investor lending limits and moved more towards sustainable qualitative lending controls through scrutinising household expenditure and total debt holdings. In May 2019, APRA removed the minimum interest rate serviceability measure, which increased borrowing capacity for households by ~10-15%. Despite this change, lending standards are still tighter than a few years ago.

The recent housing cycle in Australia

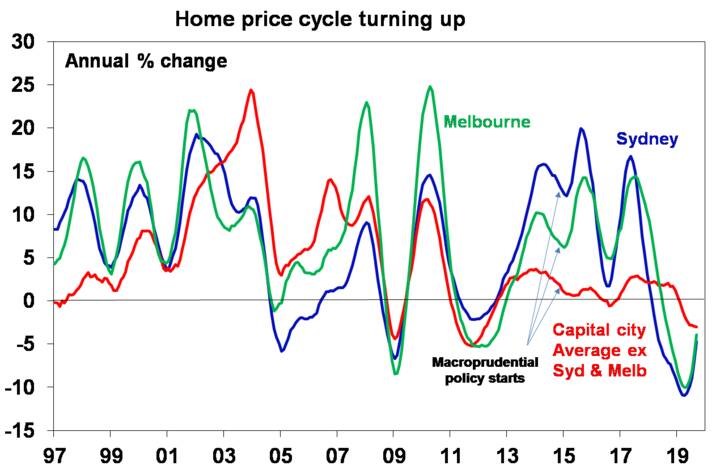

Home prices bottomed in June this year. The re-election of the Liberal Government removed the risks around changes to capital gains tax and negative gearing. The rapid recovery in Sydney and Melbourne (see chart below) has led to concerns of another unsustainable housing upswing and a further build-up in household debt. However, tight lending standards, low foreign demand for housing and a weaker economic environment (we expect the unemployment rate to rise) should limit home price growth.

Source: CoreLogic, AMP Capital

What types of macroprudential tools could be used in future?

Investor lending is considered riskier because investors are generally more leveraged, more likely to take out interest-only loans and are more likely to exit the housing market in times of stress which can exacerbate housing downturns. However, to offset these risks, Australian housing investors generally have higher incomes and wealth positions and use interest-only loans for their tax strategies. The current upswing in home prices does not appear to be driven by investors yet.

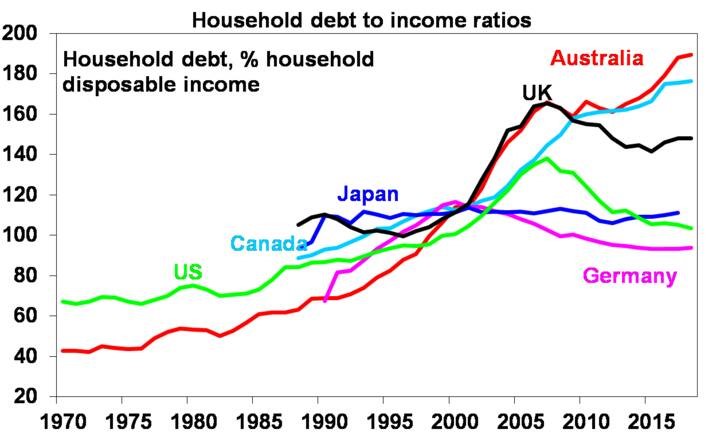

At the moment, the more worrisome part of the Australian housing market is overall high household indebtedness, mainly housing debt, currently at 190% of household disposable income, which is extremely high compared to global peers (although it has been high relative to the rest of the world for a while – see next chart).

This level of housing indebtedness has raised concerns that APRA could introduce debt-to-income (DTI) caps or even restrictions around high loan-to-value ratio (LVR) loans. The highest risk loans with debt levels six times or more above incomes make up a small amount (around 15% of new loans) while less than 10% of new loans have an LVR ratio above 90% and the proportion of these risky loans has generally been declining over the past few years.

Source: OECD, AMP Capital

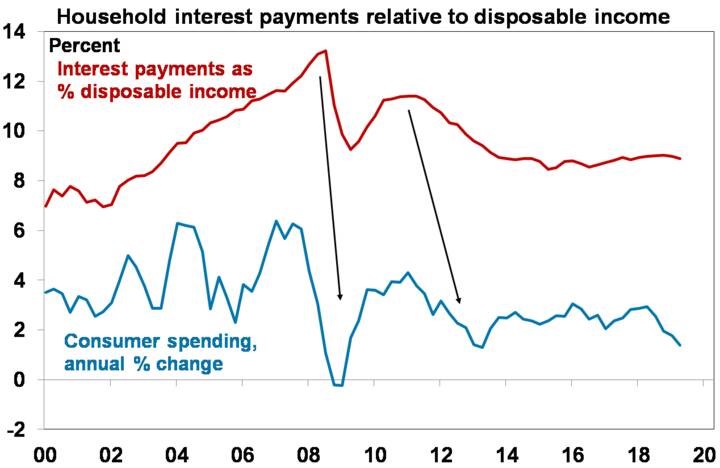

We think it is unlikely that APRA will impose specific DTI or LVR caps. High household debt is an issue if home loan serviceability is unsustainable. But this is not really an issue in Australia, as shown below. Interest payments as a share of disposable income have been stable at 9% for years and are unlikely to rise while interest rates are falling.

Source: RBA, ABS, AMP Capital

Source: RBA, ABS, AMP Capital

Imposing restrictions for DTI or LVR levels would help to reduce housing debt levels but it would also create unnecessary distortions in the market by excluding first home buyers, single person households and buyers who are trading up. Inequality issues could also be created as borrowers with means to draw on funds get around the rules.

Tightening lending standards further (by additional analysis over borrower expenses and total debt holdings) or bringing back a minimum interest rate measure for serviceability would benefit financial stability, as much as DTI or LVR cap with less market distortions.

The risks for financial stability from here are mainly down to household serviceability and how it would react to a deterioration in the economic environment, particularly given:

- wages growth is low, at just over 2% per annum

- the unemployment rate is likely to drift a little higher (to around 5.5% over the next few months), and

- a high proportion of the labour force is still underemployed (at around 13.5%).

While housing arrears are currently low at less than 1% of all loans, they could drift up if the employment market deteriorates. APRA should focus on further strengthening lending standards when assessing individual borrower serviceability as its main macroprudential instrument.

Diana Mousina is Senior Economist - Investment Strategy & Dynamic Markets at AMP Capital, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

To hear more investment news and insights, join AMP Capital’s Chief Economist Shane Oliver and Senior Economist Diana Mousina at a free webinar on 4th December discussing 2020 vision: an exclusive analysis and discussion of market conditions at home and abroad for 2020.

For more articles and papers from AMP Capital, please click here.