Okay, so you want a comfortable retirement, but do you have any idea of the savings required?

According to research from the University of New South Wales, to receive the equivalent of an average wage in retirement, approximately $85,000 p.a. before tax, you’ll need to save about 15 to 20 times that amount. That's $1.3 million to $1.7 million at today’s prices.

The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia has also looked at this question. As opposed to total savings, they focus on income requirements for a ‘comfortable’ lifestyle, with their current estimates (June quarter 2019) being $43,601 p.a. for a single person and $61,522 for a couple. And if you accept their estimates, then you’d want to avoid relying on social security alone, with the age pension currently paying $24,081 p.a. for singles and $36,301 for couples.

What amount do I need to save?

Let’s say you are 59 and your partner is 57, and you both want to receive a ‘comfortable’ amount in retirement, which is about $61,500 p.a. after tax. At those ages, it could be expected that on average you will both live into your mid 80s or later. In addition, it is reasonable to assume that:

- The income you and your partner receive will be indexed in line with the Consumer Price Index (CPI), say 3% per annum. This will be in line with inflation.

- Any pension paid from your super fund is expected to last for your life expectancy and then paid to your partner for their life expectancy. This is increased by five years to consider the likelihood of you living longer.

- The estimated level of income earned on your retirement savings is estimated as 7% per annum which is a long-term rate, net of tax.

While these assumptions may be considered unusual in the current economic environment of low inflation and low interest rates, we are considering a long-term horizon of 40 years or even longer.

If we use these assumptions, it is estimated that the total amount required in today’s money is slightly over $1.141 million.

How much do I need to contribute to meet that target?

Having estimated the amount required, we need to work out how it can be accumulated. Important considerations include: how determined you are to save for retirement; the benefit of compound interest and; the age you start saving. Let’s look at the difference if you started saving for retirement at 20 compared to 50.

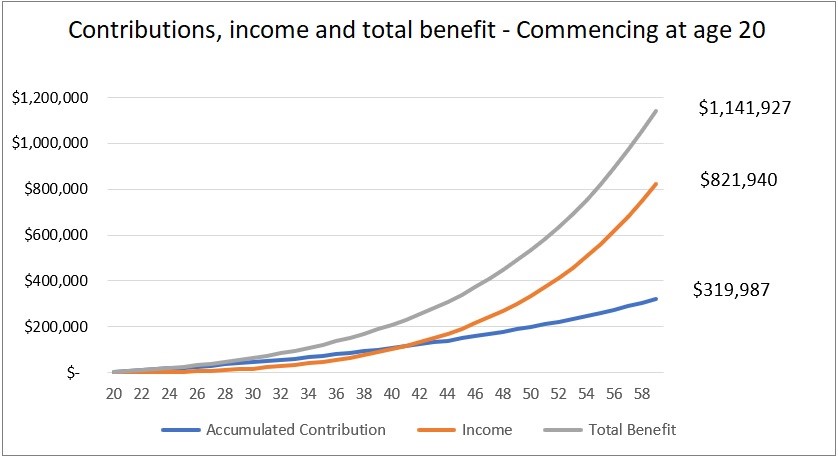

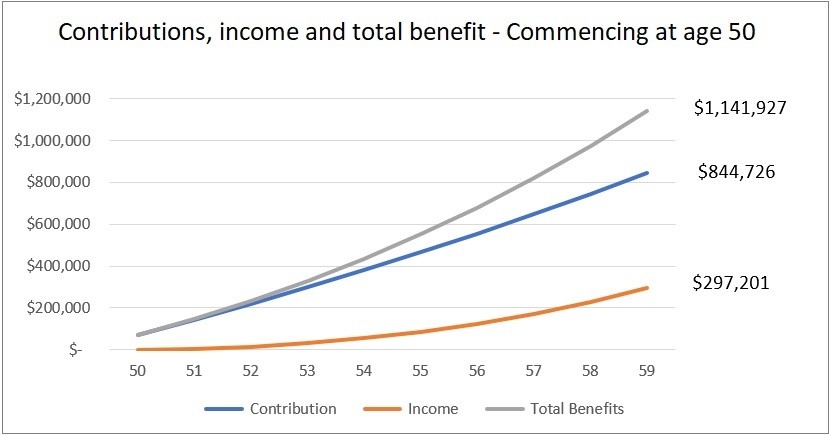

By beginning at age 20 – and to accumulate about $1.141 million – the amount you need to contribute each year starts at about $3,367 p.a. If you begin saving at 50, the equivalent figure is $70,358 p.a.

The advantage of starting at age 20 compared to 50 can be illustrated in the two following tables. These show how much of the final amount accumulated in super will be made up of the contributions themselves and corresponding investment income. Starting at age 20 means a greater proportion of the final benefit will be investment income.

When will the money run out?

The hardest question to answer is ‘how long will your super last’, which can be influenced by many factors including unforeseen drawdowns, emergencies and market forces. For instance, you may need to withdraw an unexpected lump sum soon after retiring to pay for age care accommodation or other health needs. Or there be significant long-term changes to rates of return on investments, or inflation may nibble away on the value of your super.

It is possible that you or your partner may die earlier than expected, leaving your remaining super to your surviving spouse or other beneficiaries. The amount required to live on and the timing of the payments are not easy to predict.

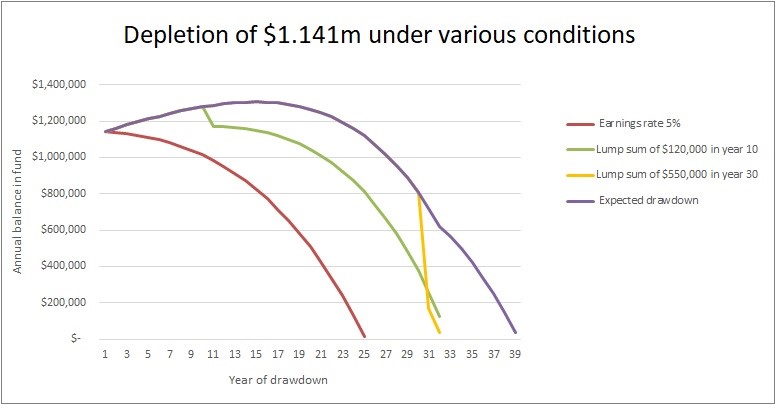

Assuming a target savings amount of $1.141 million, let’s see how long the money would last for based on an expected drawdown of $61,500 p.a. indexed to CPI plus three additional variants:

- Long-term interest rate drops to 5% p.a., instead of an expected 7% p.a.

- A lump sum withdrawal of $550,000 is made in the 30th year after retiring

- A $120,000 lump sum is required in the 10th year after retiring

From this chart we can see that the quickest depletion is caused by a lower-than-expected earnings rate (5% p.a. instead of 7% p.a.), with a nil balance being reached by the 25th year post-retirement.

If $550,000 is drawn down in the 30th year, the amount in superannuation would run out in year 34.

And if $120,000 is withdrawn in year 10, the amount accumulated would last to the 35th year.

Graeme Colley is the Executive Manager, SMSF Technical and Private Wealth at SuperConcepts, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider any individual’s investment objectives.

For more articles and papers from SuperConcepts, please click here.