The received wisdom that investors should “take a long-term view” is as well-worn as it is simplistic. Because while the long run certainly matters, when it comes to investing in transition materials there’s also a strong case to make for a bit of constructive myopia. By that we mean keeping a very close eye on the near term – staying on top of both commodity market fundamentals and those of the producers in each market – and not being so focused on a good growth story that it leads to expensive decisions. Demand is important but the ability of new supply to meet that demand is often neglected and is just as important – if not more so.

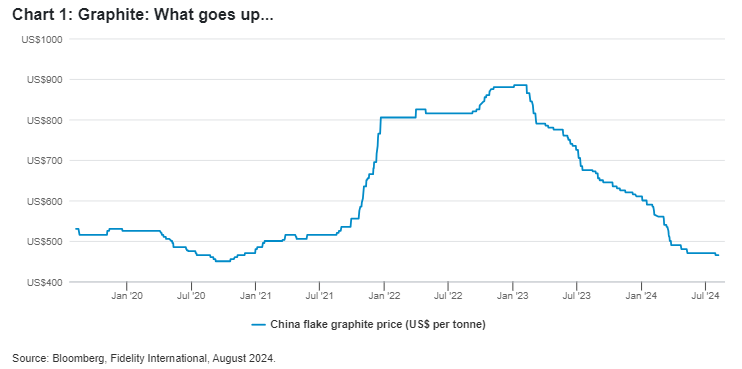

Graphite is a good example. The mineral has a tremendous long-term clean energy story thanks to its role in the batteries that power electric vehicles. But if you’d invested in a graphite producer a year ago you would have lost money.

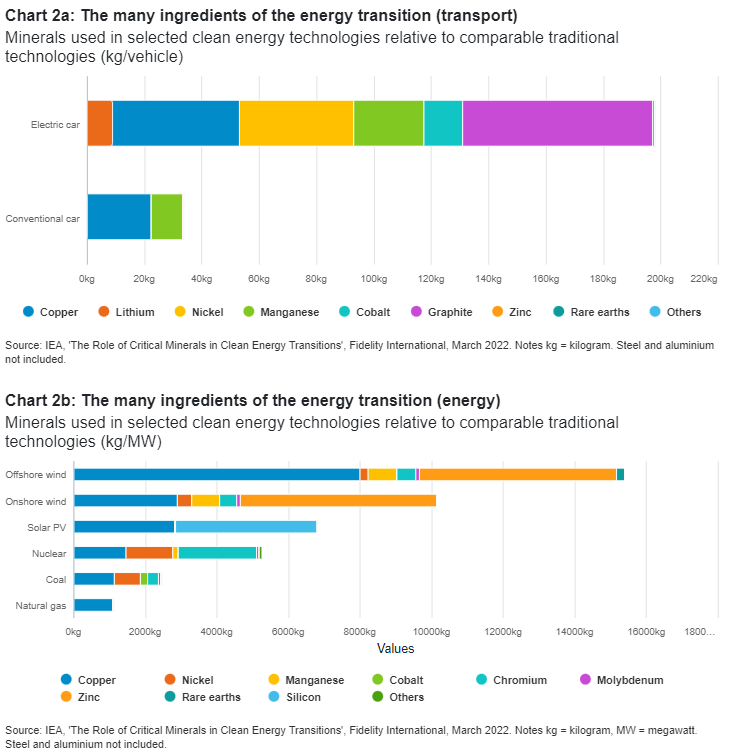

Timing clearly matters, and there’s a balancing act to perform between short- and long-term dynamics. Commodities are a bottleneck in the clean energy transition. From copper to agriculture, decarbonisation-driven demand is hitting supply networks that aren’t always set up to meet it. That triggers a response. As supply of, say, copper struggles to keep up with demand, there’s an increased incentive to swap to other materials, to supply more scrap copper, and to use the metal more efficiently.

What incentivises all these behaviours is a higher copper price, and there’s an obvious way to profit from that if you can spot the bottlenecks as they emerge.

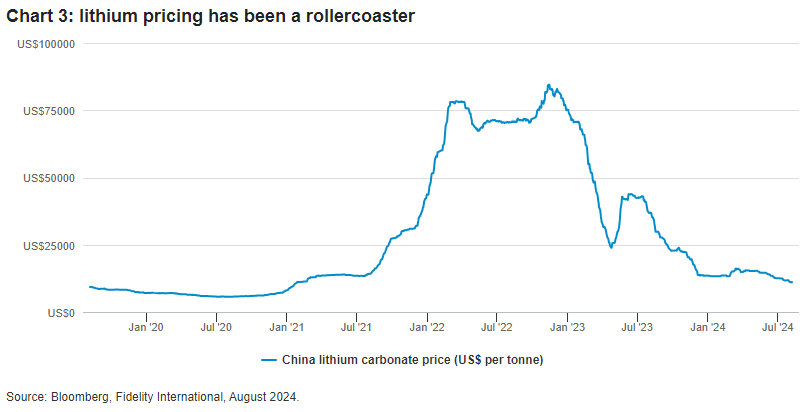

But that’s only part of the story. The more a commodity’s supply is capital constrained – as opposed to resource constrained – the greater the ability to respond quickly to surging demand by boosting supply, and so the less likely those bottlenecks will persist. Take lithium, where a huge shortage in the early part of this decade was followed by a big run-up in price. Lithium, however, is in fact relatively abundant. So, predominantly Chinese producers responded to the higher price and ramped up supply, driving the price back down again, to a level we think is too low to support the investment economics of Western producers – which, in turn, is laying the ground for the next up-cycle.

Take a broad view

Graphite and lithium highlight why commodity choice matters. At least half the work our team does is top-down, identifying which commodity markets look most promising near-term. We try to take a broad view and consider potential ripple effects. Copper, for example, is widely considered a transition material, but fewer investors take the same view of aluminium. Yet the International Energy Agency has reported that a third of projected growth in copper demand arising from expanding electricity grids could be met by aluminium.

The supply chain for renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel shows some similar dynamics. Low carbon feedstocks, such as fats and used cooking oil, have a structural advantage under the Inflation Reduction Act in the US and we think these feedstocks will remain scarce. What was once a waste product will, we think, be increasingly valuable over time. The oil used to fry your chips in McDonald’s one day will potentially be flying you on your summer holidays.

Ammonia too is a commodity we think has an interesting future. The current ammonia market centres around its use as a fertiliser. But it can also be used as a fuel, including for shipping, a sector that faces almighty challenges in its attempts to reduce emissions. As a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen, ammonia is useful for the transportation of green fuel (cheaper and safer than moving pure hydrogen around) and could be used to reduce emissions in a number of high-carbon industries. These use cases potentially give ammonia a big role in the clean energy transition that could double the commodity’s overall market over the next 10 to 15 years.

Commodity prices: reliably unreliable

Of course, all the analysis in the world won’t guarantee getting the commodity story right every time. These are, after all, famously volatile markets and a focus on the top down doesn’t mean you can neglect the micro. You need a margin for error.

This is where company analysis comes in, including a consideration of sustainability. A focus on low-cost makes sense because what you want is a stock that can sit tight when its sector is under pressure and still generate cash at the bottom of the cycle. It means you can be confident that its share count is likely to be the same when things pick up because it hasn’t needed to issue new shares to raise capital. It’s about finding that happy medium between growth and free cash flow producing assets.

A word on political (and geopolitical) risk

That brings us to a topic that’s hard to avoid when investing in producers of transition materials: political risk. Our somewhat idiosyncratic view on the subject is that we would rather make cash flows through the cycle from high-quality assets in more risky spots than guarantee low-risk sub-par returns in so-called ‘safer’ regions. Because political risk is not static. Chile, for example, has in the last few years gone from being a low-risk jurisdiction to briefly being a high-risk one, and back again. And in 2022, Australian authorities in supposedly safe Queensland saw no issue with imposing a very punitive royalty on mining companies’ metallurgical coal revenues.

Political risk is unavoidable and is something we have to manage. It helps to start with solid cash flows from a low-cost asset and then manage that risk, rather than needing the commodity to do you some big favours.

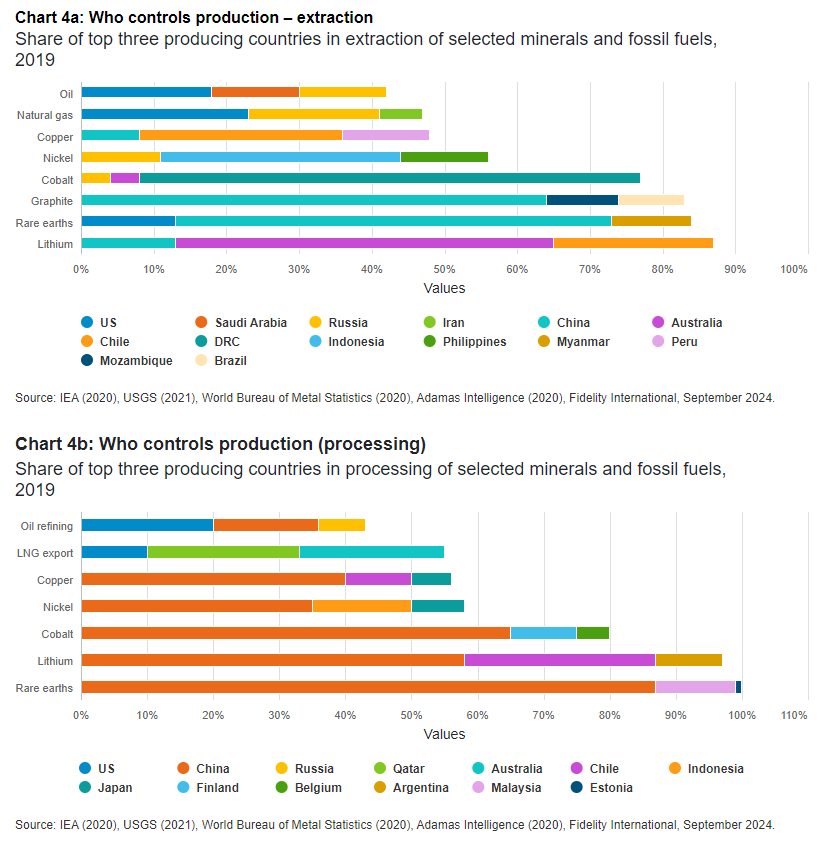

Geopolitical risk, on the other hand, has a direct bearing on commodity cycles and future price formation. While China has a moderate endowment of critical minerals that will play a big role in the energy transition, it dominates processing. Moreover, at a time when Western companies have pulled back from allocating capital, Chinese state-owned enterprises have forged ahead with mining investments all over the world. Nickel, for example, is largely produced in Indonesia but a significant part of that production is Chinese-owned and almost all of the growth projects have Chinese partners.

The upshot is that Chinese investment in critical mineral production is keeping a lid on prices, which in turn makes it difficult for Western producers to invest at these levels. If certain countries want China-free supply chains of critical minerals, it will require the incentive of higher prices for producers. In practice, this is likely to mean some commodities having an international price that is higher than the Chinese price, as has happened to a degree in polysilicon.

This sort of dual pricing will need to become more widespread if Western producers are to feel confident that they can make profitable investments in growing the supply of transition-critical commodities. There is a clear strategic angle to this, and we’re watching closely how governments might try to incentivise producers.

Top-down and bottom-up: both matter

Investing in the energy transition is a long-term play, one that requires expertise in commodity markets and the companies that operate in them. In practice, that means not just making bets on which commodities will win big ‘eventually’. Because to benefit from the long-term macro trends, it’s essential to stay on top of the micro details and understand each producer’s business, as it is today.

Oliver Hextall is a Portfolio Manager of the Fidelity Global Demographics Fund. Fidelity International is a sponsor of Firstlinks. The views are his own. This document is issued by FIL Responsible Entity (Australia) Limited ABN 33 148 059 009, AFSL 409340 (‘Fidelity Australia’), a member of the FIL Limited group of companies commonly known as Fidelity International. This document is intended as general information only. You should consider the relevant Product Disclosure Statement available on our website www.fidelity.com.au.

Read the full report and relevant disclaimers here.

For more articles and papers from Fidelity, please click here.

© 2024 FIL Responsible Entity (Australia) Limited. Fidelity, Fidelity International and the Fidelity International logo and F symbol are trademarks of FIL Limited.