Economic rationalism – that is, a belief in free markets, deregulation, and globalisation – has been a hallmark of progressive governments in the West since the demise of socialism. While these policies have sustained productivity and growth, the spoils have not been evenly shared as living standards in low and middle income households have stagnated in many developed countries. The median income for an American male is unchanged in real teams over four decades. The promise of open markets and capitalism has sadly failed the middle class and their dissident voice is becoming louder.

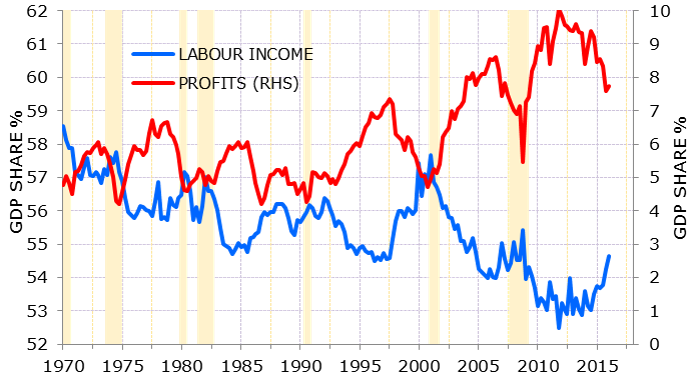

You can see a clear divergence emerging in the share of incremental growth going to labour versus capital by way of profit share in the graph below.

US labour income and profit share

Source: Minack Advisors

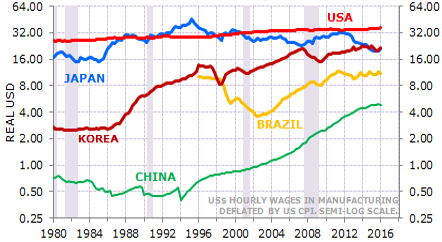

Owners of capital, aka the wealthy, have benefited tremendously from soaring returns on capital. Real wages on the other hand have lagged well behind productivity improvements. The impact of globalisation on low-skilled jobs has been an important contributor here. As capital has shifted to lower labour-cost destinations, the owners of capital have benefited from the immediate uplift in productivity, while the workers that have been displaced have seen living standards fall. The graph below illustrates the 10-fold increase in real wages in China versus stagnation in the US and Japan.

Manufacturing hourly pay in real US$ terms

Source: Minack Advisors

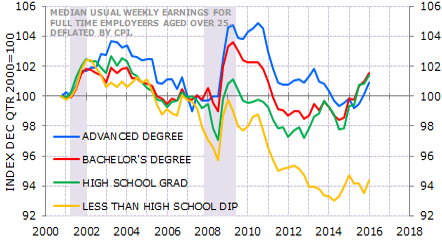

Migration and open borders, another feature of globalisation and political union, has intensified this threat to job security. In the graph below, you can see how immigration has put downward pressure on the real wages of unskilled workers in the US. Austerity policies in the aftermath of the financial crisis have further stressed households dependent on social services. To them it seems unfair that the banks get bailed out yet they pay the cost through austerity.

US weekly median pay by education level

Source: Minack Advisors

Falling interest rates, another feature of the ‘great moderation’ of the past 20 years, have only exacerbated this trend toward inequality. Those who own most of the assets have benefitted as asset values have been bolstered by lower interest rates. The asset poor have missed out, while real wages have fallen.

Financial markets and politicians missing the signals

The disenfranchised are rejecting these liberal beliefs, giving rise to the nationalist and extremist views that are gaining popularity in many western countries. The unexpected Brexit result in the UK, the ascendancy of Donald Trump in the US, and the rebuke to the LNP in the Australian election are all manifestations of this. The political class appear detached from the shift in public opinion. Financial markets, where the true acolytes of the neoliberal church reside, are even further removed. A consequence is the ongoing failure of markets to recognise the importance of this protest vote and the potential impact on favourable policies that have been tremendously beneficial to investors.

The shift in political mood and the prospect of a reversal in these market-friendly policies are a negative for the market outlook. The political establishment also seems a long way from recognising the problem. Consider the retribution to Brexit voters the European Commission is calling for, clearly far from a workable solution.

Make no mistake; this is a very loud voice, a voice that will become louder until we see a reversal in the divergent trends in the above graph. In the meantime, the political risks will grow, unsettling financial markets.

Shifting demographics, weak productivity and deleveraging are all features of slowing global growth. The precipitous fall in bond yields in recent weeks reflects this outlook, with many bonds now trading below the zero bound. Australia’s 10-year government bond rate has slipped to 1.8%, fractionally above the cash rate. With the yield structure so flat and no carry or compensation for duration, it is hard to see any scenario where bonds can deliver anything but horrible returns in the medium term. Investors have been left with few choices, explaining the resilience of shares in the face of disturbing developments both politically and economically.

We feel more confident than ever in the merits of hedging strategies like those employed by Watermark. Bond yields are telling us the outlook for growth is as weak as it has been in a generation. There is no carry; a passive, buy and hold strategy will deliver low returns at best. Only an active strategy that can deliver enhanced returns through security selection stands a chance of delivering acceptable returns in this climate.

Justin Braitling is Chief Investment Officer at Watermark Funds Management. This article is for educational purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.