If the emerging boom in Generative AI (GenAI) is to follow the evolution of the internet, today’s enthusiasm and capital deployment could only be beginning.

In this sense, the release of ChatGPT in 2022 has been likened to the release of the Mosaic browser in 1993, which popularised access to the World Wide Web and released a torrent of investment and interest in the emerging technology.

As with GenAI today, the early days of the internet boom were characterised by recognition of the technology’s transformative potential but uncertainty around the specifics of the opportunity set.

Ultimately, the internet boom featured three main categories of company:

- Backbone companies that were ‘picks and shovels’ plays on internet infrastructure. Members of this group included telecom, cable and networking hardware companies.

- Gateway companies that provided the hardware and software needed for people to access the internet. Notable members of this group included the PC manufacturers and the “Wintel alliance” of Microsoft Windows software and Intel chips installed in most of the devices.

- Destination companies – the dot-com internet businesses that aimed to give internet users things to do and buy on the World Wide Web. Notable members of this group included eBay, Amazon and several doomed ventures like WebVan and Pets.com.

Today, businesses are just beginning to build out the infrastructure to deploy GenAI. As a result, today’s most-talked-about GenAI stocks tend to be backbone-like investments. These include chip companies Nvidia and Micron, hardware company Super Micro Computer, and cloud services companies like Amazon and Microsoft Azure.

Today’s GenAI gateways include OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s CoPilot, and Google’s Gemini/Bard. Although recent progress in improving the accessibility of GenAI has been rapid, these tools have not yet reached the ease-of-use that Windows gave to PC users to spark ubiquitous adoption. Further improvements over the next few years should prove exciting.

More and bigger opportunities to come?

With this in mind, the GenAI investment cycle is likely to last years and there could be far bigger opportunities still to come.

Consider that three of the most dominant companies of the tech ecosystem today played little role in the internet boom of the 1990s. Alphabet did not go public until after the internet boom (2004). Meta wasn’t founded until 2004 and went public in 2012. Apple existed during the bubble but was a dark horse.

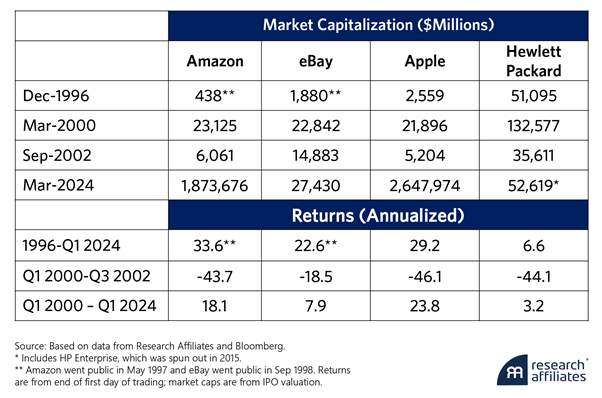

Indeed, Apple has the most impressive and unlikely story. Not only was the company considered an also-ran to the main internet darlings, it nearly went bankrupt in the 1990s. At the bubble peak in 2000, Apple, Amazon, and eBay all had similar market caps. Today, Apple’s market cap is 40% larger than Amazon’s and 96x larger than eBay’s.

Table 1: Relative Market Cap and Total Returns Over Time

Amazon, eBay, Apple, Hewlett Packard

In various ways, the ultimate success of today’s giants depended heavily on investments inspired by the internet boom.

While the tech bust destroyed billions of dollars in capital, the investments made during the boom in communications, chips, software, and hardware allowed companies to build newer and more innovative applications and businesses. Apple’s iPhone, for example, would not have been possible without the investment in mobile communications infrastructure.

These investments and new products have also accrued to the benefit of society. The lower price of broadband makes high-speed internet and mobile communications affordable to a wider audience, enhancing productivity and convenience for all of us.

Lessons learned from the dot-com boom

1. Capital discipline is paramount—fundamentals ultimately matter

The worst failures of the internet boom were the companies that could not finance their own growth and had no tangible plans to earn a return on capital. Not all financially strong companies had an easy time in the bust. But these companies at least survived and delivered some value to their shareholders over time. Capital discipline is necessary not just for corporations but also for investors. Those who invested in profitable, well-capitalized tech companies in 1996 fared well over the long term. Those who piled into speculative companies at the height of the mania while eschewing “old economy” stocks often experienced significant losses.

2. Picking winners (and losers) is hard—better to own a diversified portfolio.

With hindsight, picking winners looks easy. But even once seemingly invincible companies, such as Intel, can falter, and some of the biggest winners of the internet revolution only emerged later. Likewise, picking losers is difficult, as technology and its use evolve in unexpected ways. For example, while some prognosticators predicted the end of using office paper, the spread of personal computing and printing peripherals actually increased paper use for many years. The evolution of GenAI will also be unpredictable, and it is likely that some of the greatest GenAI companies have yet to emerge.

3. Technological progress benefits us ALL—stay invested and diversify

The excesses that culminated in the dot-com bust were extremely painful and capital destructive. Despite the massive misallocation of much capital, some of that capital built useful networks, software, and databases, creating a framework to launch great businesses and increase productivity. While dot-com companies were once seen as niche businesses, every company now has a website. Households enjoy the convenience of online shopping from a myriad of businesses. Zoom would not have been possible without prior broadband investment.

Reflecting these broad qualitative benefits to society, investors that showed discipline also gained.

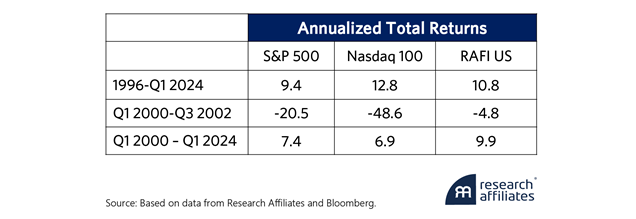

The table below shows the 25-year performance of the S&P 500 index, the more tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 and the RAFI™ US Fundamental Index, which owns almost all the companies in the S&P 500 and Nasdaq 100 but weights stocks by fundamentals rather than mania-induced prices.

Table 2: Performance of US Equity Indexes Over the Past Quarter Century

As the price mania in internet companies unfolded, the S&P 500 became more exposed to tech stocks in early 2000 and the Nasdaq 100’s increase in exposure to internet themes was even greater. Nevertheless, an investor who allocated capital at the end of 1996 (early in the internet boom) would have achieved double-digit returns from both the RAFI strategy and the Nasdaq 100 over the next 27 years.

Had the same investor allocated at the peak of the bubble in March 2000, returns would have been lower but still fairly good. This is particularly true for RAFI US investors because that index did not get as over-allocated to tech in 2000.

The only investor to suffer significant capital loss was the one who piled in at the peak and sold out over the next 18 months. Even then, a RAFI US investor would have suffered a much smaller drawdown. In the long run, the productivity benefits of the internet boom have benefited businesses and investors beyond the tech sector.

A note of caution

As optimistic as we are about the potential of GenAI, we would not be acting responsibly if we failed to point out some challenges the new technology could face. The main challenges are carbon intensity, regulation and de-globalisation.

- Large language models (LLMs) that read and process thousands of documents in seconds consume large amounts of energy. As use of these models spreads, the competition for energy resources could drive prices to a level that would make certain GenAI activities uneconomic. Additionally, as governments and companies increasingly commit to environmental goals, would society continue to allocate energy resources towards GenAI? Could GenAI continue to grow without cheap computing power, which increasingly means cheap energy?

- New technologies always spawn some level of fear and distrust. While the internet emerged during a time of de-regulation, the tech bust and the Great Financial Crisis curtailed that ethos. Today, our society is more amenable to reigning in large tech and new tech. Already, copyright challenges are putting limits on the amount or types of information that GenAI models can use. Regulation could emerge in other areas as well, including privacy, safety, and discrimination. Can the cost of adaptation be overcome?

- The internet emerged during a long period of globalization. The Berlin Wall had fallen, the number of former communist nations was increasing, and movement of goods as well as human capital flowed more freely. This global integration provided resources in capital and human capital to make rapid progress in technology and business ideas. With today’s world possibly on a path of de-globalization, there could be a sustained trend of rising barriers to the movement of people, capital, and ideas. Will the necessary resources be available to make the rapid advancements that a GenAI boom would require?

While we do not believe these challenges to be insurmountable, investors should bear these risks in mind as GenAI evolves.

Concluding remarks

To be sure, not every mania creates something useful and enduring. Tulips and perhaps cryptocurrencies might be seen as less-than-useful manias. However, if GenAI is as revolutionary as we think it will be, a mania is likely to develop.

In the event of a GenAI bubble, capital will be misallocated and fortunes lost. On balance, though, the gains will be greater than the losses. Society and investors will ultimately benefit, and these benefits will be felt very broadly beyond the immediate GenAI companies.

If investors believe that GenAI will be as impactful as the internet, they will need to participate by getting invested, and the best approach will be to stay diversified and be prepared to hold through ups and downs.

Those who have a high threshold for risk may opt for a highly concentrated approach in current behemoths, such as the Nasdaq 100. Those who believe the benefits of AI will be shared broadly and that winners may change over time should opt for a fundamentally based approach with disciplined rebalancing, such as the RAFI Fundamental Index strategy.

Que Nguyen is a Partner, Chief Investment Officer, Equity Strategies lead, and a member of the Management Committee of Research Affiliates. Please read Research Affiliates’ disclosures concurrent with this publication: https://www.researchaffiliates.com/legal/disclosures#investment-adviser-disclosure-and-disclaimers. This is an edited version of the original article, linked here.