The newly-minted ‘OK Boomer’ movement is increasing attention on generational inequity. The New York Times of 29 October 2019 carried this heading:

‘OK Boomer’ is used by Gen X, Gen Y (Millennials) and now Gen Z (the newest generation) when a Baby Boomer says something dismissive, especially referencing the good old days. The younger person cannot be bothered explaining the ignorance of the older generation, and simply responds with ‘OK Boomer’. It’s pejorative, a put down. It has already been used in the New Zealand Parliament by a 25-year-old politician to stop heckling during a climate change debate.

Financial equality between generations is an emotive issue with legitimate arguments on both sides. Older Australians want to hang on to the outcome of their hard work, as they have legitimately planned for retirement based on a set of prevailing rules. Younger people see the Boomers enjoying property market, superannuation and investment conditions unlikely to be repeated. Already, the 27% of Australians who are over 50 hold half the wealth, and ASIC estimates 65% of the almost $3 trillion in super is held by fund members over 50.

Confining this article to financial matters, we will focus on:

- Superannuation contributions

- Residential property prices and the family home

- Equity and bond markets

- Cost of education

- Death duties

- Demographic change

It avoids the big social issues such as climate change, global political unrest, #metoo, over population or trade wars. Rather, let’s see how Boomers’ conditions have allowed them to build financial independence in retirement.

Now it’s ‘When I’m 84’

In 2014, Alex Denham, then a financial adviser, wrote an excellent article called ‘Hey, what have you got against late 60s babies?’ Born in 1969, she feels her generation missed out on many of the advantages that set up older (and in some cases, younger) generations:

“I’m getting a niggling feeling that someone out there has it in for us late 60s babies. We just seem to keep getting hit by changing government policy, and not in a good way. Too old for this, too young for that.”

At the time of publication, I recognised that many of the benefits had gone to Boomers. Born between 1946 and 1964, Boomers are now aged 55 to 73. I was born in 1957, the same year two lads named Paul McCartney and John Lennon first met, down the road from my birthplace. ‘When I’m 64’ is suddenly only two years away for me. I recently attended an amazing McCartney concert where he performed without a break for three hours in a spectacular collection of classics. He was born in 1942 and is now 77 years-of-age. Next time … ‘When I’m 84’.

1. Superannuation contributions

Super schemes existed for many employees before the introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) in 1992. By 1974, an estimated 58% of the public sector and 24% of the private sector had some form of super. However, SG was a massive step forward for widespread inclusiveness when it started at 3% in 1992 under the Keating Labor Government. The compulsory contributions gradually reached 9% by 2002/2003, and the current level of 9.5% was set in 2014/2015.

A Boomer born in 1964 may not have received compulsory super until the age of 28, and would have been 38 by the time the 9% level was reached. It could be argued they have not received the full impact of the super system.

This disguises the limits and the generous ability to put more into super which operated for much of their working life. The limits have been reduced significantly for the following generations. The current maximum annual concessional contribution, the most tax-advantaged way to put money into super, is only $25,000. At various times in the past, this has been as high as $100,000 a year, and was $35,000 for people 49+ as recently as 2017.

The biggest opportunity to put large amounts into super comes from non-concessional limits, the amount from after-tax savings. The current non-concessional cap is $100,000 a year, but for three years until FY2017, it was $180,000 a year, and $150,000 a year for many years before that.

One reason many wealthy people have so much in super is Treasurer Peter Costello allowed $1 million in non-concessional contributions for a period of 14 months until 30 June 2007. Although there was no limit on after-tax contributions before 2007, pensions were taxed so the environment was not as attractive.

What made money in super so appealing was that in December 2006, Costello introduced a Bill to allow people aged over 60 to access their super tax-free. Not only are the earnings on assets in pension phase free of tax, but withdrawals (following a ‘Condition of Release’ until the age of 65) are also tax free, whether as a lump sum or pension.

This explains why the then Treasurer, Scott Morrison, in the 2016 Federal Budget capped the amount that can be transferred to the pension phase to $1.6 million. Anyone with a total superannuation balance greater than or equal to the transfer balance cap now has a non-concessional limit of zero. Super above $1.6 million must be held in accumulation with a tax rate of 15% on income earned (or 10% for capital gains), still highly advantaged versus the personal tax system.

The tighter caps make it far more difficult to establish large superannuation balances, especially via the concessional limits. The $100,000 years were massively advantageous for high-income earners. In 2016, when the Commissioner of Taxation, Chris Jordan, explained why 2,184 people had over $10 million in super (and six with over $100 million), he said the balances had been accumulated over 30 years or more. That’s what high limits, good investing and compounding can achieve.

The rules around a ‘Condition of Release’ are surprisingly flexible. A person over the age of 60 does not even need to retire, they simply need to resign from a company. They can start work again the next day while also setting up a pension. Although the limits were tightened, a couple can still move $3.2 million into the tax-free phase.

While there is a requirement to take out the legislated minimum of 4%, anyone with other resources will leave the rest untouched because saving in super is subject to such low tax rates.

Let’s face it, if a couple with a large super balance pays no tax on $3.2 million of assets and only 10% to 15% tax on the rest, then Australia is not collecting taxes from many people who can afford them (acknowledging that tax was paid before the money went into super). Even if they earn only 5% on $3.2 million, that’s $160,000 of tax-free income which might otherwise incur personal tax at 45% plus a Medicare Levy of 2%. That's over $75,000 a year which can finance a decent Mercedes or a couple of amazing trips to Europe a year. Seven hundred Australians retire every day.

2. Property prices and the family home

The first property I bought in Sydney in 1980 cost $56,000, for a three-bedroom terrace. It’s now near a train station and would be worth maybe $1.5 million. Adjusting $56,000 in 1980 to current day dollars (using the RBA’s inflation calculator) gives $241,000. The real cost is up by 330% over 38 years, but that’s only 3.9% a year for inflation.

The second house, this time free-standing on the Lower North Shore, cost $104,000 in 1983. Let’s guess it is now worth $2.5 million. Current day dollars for the $104,000 is $333,000, a change of 220% at an average inflation of 3.4%.

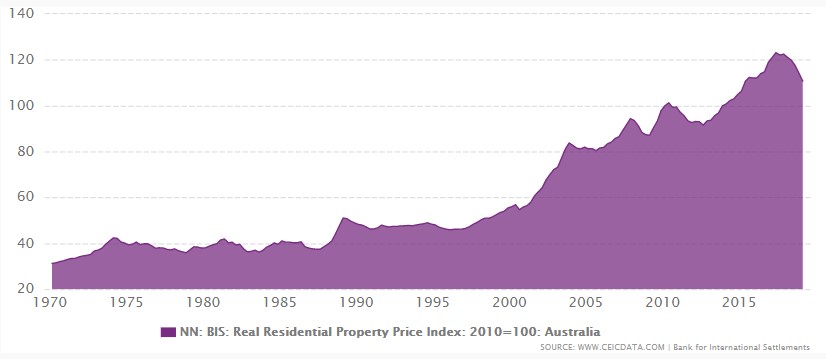

These examples are typical, give or take, of millions of people who entered the property market 20 to 30 years ago. The following chart shows real property prices for Australia since 1970, adjusted for inflation. The index is set at 100 in 2010, and this is not the most expensive markets of Sydney and Melbourne.

It shows how far ahead of inflation, and similarly wages, house prices have risen, although it’s not a straight line. The index rose from 1970 until 1975 and then held its real levels for the next dozen years, with a strong kick up before the ‘recession we had to have’ in 1991. Many houses purchased in 1990 were worth less five years later. And yes, interest rates in the late 1980s were much higher, with the variable rate at around 13.5% for most borrowers. But anyone owning a house for the last 25 years has materially benefitted.

Australian Real Residential Property Price Index from March 1970 to March 2019

With this increase in wealth, consider what owning a family home gives under our current system:

- Tax-free capital gains. I asked a fund manager many years ago where he invested his own money. He said that while he held his liquid assets mainly in his own fund, the best investment for tax-free capital growth was Sydney houses on large blocks of land in great suburbs. And in his case, it needed to come with its own tennis court.

- Exemption from social security assets tests. Even for most people who have not accumulated much wealth outside the family home, but spent their life paying off their mortgage, they are now sitting on a substantial asset in retirement. A couple can receive a full age pension with other benefits such as cheap medical prescriptions if their assets outside the home are less than $394,500, and part pension up to a healthy $863,500. They can top up their cash flow through the Pension Loans Scheme up to 150% of a qualifying pension (the maximum age pension for a couple is $36,582 a year, plus pension and energy supplements). There are many reverse mortgage schemes which also give access to lump sums if needed.

For all the attention we rightly pay to superannuation, it is the ownership of a home, exempt from assets tests but giving access to cash flow through a reverse mortgage, which offers the greatest financial security and independence in retirement. Due to property inflation, newer generations are finding it far more difficult to reach this milestone, increasing the uncertainty of their futures.

3. Equity and bond markets

To avoid doubling the length of this article, let’s consider a few data points which show how favourable investment conditions have been over the last 30 years, even including the GFC.

The 2019 Vanguard Index Chart gives financial year returns for major asset classes, with the averages since 1990 of:

- Australian shares, 10.0%

- US shares (unhedged), 11.8%

- Australian bonds, 8.3%

- Australian listed property, 10.6%

Investors should be delighted if these returns are repeated in the next 30 years. Even a balanced portfolio with conservative allocations to bonds and cash has delivered close to 10%. With bond rates now at 1% and markets fully-priced, if anyone offered you these returns, bank them before they blink.

4. Free education

In 1974, Gough Whitlam abolished fees for university and tertiary education became free until the introduction of HECS in 1989. I went to university for four years from 1976 to 1979, with every year free. Now it is common for students to acquire $100,000 or more of HECS debt. I also benefitted from a Commonwealth Bank bursary that paid full salary while studying, but the Bank no longer offers such funding.

5. Death duties and super for estate planning

It is claimed that no other developed nation has policies that both exempt the family home from any form of taxation or social security test, plus imposes no death duties. It’s also argued this places the tax burden on income which is unfair to younger generations, encourages a brain drain to lower-taxed countries and reduces the turnover of property.

Australia does have a form of death duty. Non-dependant children who inherit a superannuation lump sum will pay 15% tax plus 2% Medicare Levy on the taxable component of the balance. The best way to avoid this tax is to transfer money out of superannuation the day before death. Get the paperwork ready.

This raises another point on the purpose of superannuation. While it is widely accepted that super is intended to finance retirement, the reality for many wealthy Australians is that super is an estate planning tool. Keep the money in a favourable tax environment for as long as possible before handing it over to the children, and whip it out of super before buying the coffin.

Somewhere along the way, the bank of Mum and Dad might help in the property market.

At the last Federal Election, the Coalition successfully targeted ‘death taxes’ as a Labor strategy, even thought it was not on the policy agenda. Such tactics ensure unpopular policies are removed from debate, when a death duty potentially lowers inequality and reduces reliance on other taxes. Dead people do not vote, but they enjoyed passing their wealth to their children.

6. The Intergenerational Report

Somewhere in this divide is the harsh reality of future budget constraints. The 2015 Intergenerational Report assesses the long-term sustainability of government policies looking ahead 40 years, and it includes:

- In today’s dollars, health spending per person is projected to more than double from around $2,800 to around $6,500 a year. State government costs will also be significantly higher.

- Aged care expenditure is projected to increase from 0.9% of GDP in 2014-15 to 1.7% in 2054-55, and from $620 to $2,000 in real, per person terms.

- Despite policy changes and greater super balances, payments made through age and service pensions per person are projected to increase from almost $2,000 in 2014-15 to around $3,200 in 2054-55 per person in today’s dollars.

- Most significant of all, “There will be fewer people of traditional working age compared with the very young and the elderly. This trend is already visible, with the number of people aged between 15 and 64 for every person aged 65 and over having fallen from 7.3 people in 1974-75 to an estimated 4.5 people today. By 2054-55, this is projected to nearly halve again to 2.7 people.” That’s a lot less workers paying taxes to support the elderly.

They are coming to get us

Boomers are a large voting group. High post-war birth rates and longer life expectancies mean it’s a cohort few politicians want to offend. We Boomers fight to retain our rights, as former Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen discovered when he was completely out-muscled over franking credits.

There’s little doubt the Labor Party will abandon the policy. New leader Anthony Albanese recently told the National Press Club following the review of Labor’s election defeat:

“When you’ve got to explain dividend imputation and franking credits from opposition, tough ask. While the call on the budget of franking credit arrangements is large, many small investors felt blindsided and it opened up a scare campaign.”

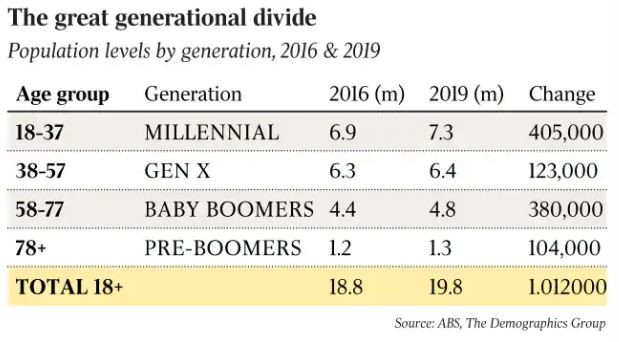

Data from demographer Bernard Salt shows Millennials already significantly outnumber Boomers, and they will increasingly hold the power at the ballot box. By 2040, the first Boomers born in 1946 will be well into their nineties and life expectancy increases will not save all of us.

Time to fess up

Of course, not every Baby Boomer has enjoyed the good times, and this article makes sweeping generalisations about opportunities. It focusses on the prevailing circumstances millions have faced, not whether they were fortunate enough to grab them. Female Boomers also did not have equality in employment and salaries.

Missing out on the war years and the immediate austerity that followed, Boomers have benefitted from a favourable superannuation system with high limits and then little or no tax in retirement, surging property prices, excellent bond and equity markets, free education and avoidable death duties … we could go on about cheap global air travel, rapid medical advances, low unemployment and a healthy environment.

The next generations worry about the climate change problems we will leave behind, how future education and health and social services will be funded, and how they will ever enter the property market.

Let’s cut a little slack and campaign less against every change that might adversely affect us. We’ve had the politicians in our pockets, next to our bulging wallets, but it will not always be that way. The younger generations include our children and grandchildren.

Truth is, it’s been good for us. OK, Boomer?

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.