What goes up must come down was the mantra of small-cap investors for decades. Yet, over the last 10 to 20 years the largest companies have become larger and larger, outperforming small caps in the process. Some new research indicates that at least in part, this might not have been the result of mega caps being operationally superior to small caps but may be due to a butterfly effect triggered by index fund flows.

Index funds have long been prime suspects in the search for reasons why large companies have grown larger over time and why the US stock market, for example, is entirely dominated by a few mega-cap tech companies. I have always been suspicious of this argument because if you buy an index tracker, you buy each stock in the index in proportion to their market cap, so investors moving from active to passive funds should not influence the relative market cap of the stocks in an index.

Yes, index investors don’t correct mispricing of stocks because they don’t care about valuations, but the stock market remains dominated by active investors, and the market share of index trackers is in my view way too small to explain why megacap stocks trade at much higher valuations than most of the rest of the S&P 500, for example.

But when I read a paper by Hao Jiang, Dimitri Vayanos, and Lu Zheng I was surprised to see how flows into index funds create a butterfly effect among large-cap stocks.

For the uninitiated, the butterfly effect describes the observation that in a complex nonlinear system, even the tiniest changes in starting conditions can lead to large changes in the result. This was commonly described as a butterfly flapping its wings creating a tornado somewhere else.

The butterfly effect was discovered by meteorologist Edward Lorenz who tried to run computer forecasts of the weather. Below is a visualisation of the simple computer model he ran in 1972. The blue and yellow cones are virtually in the same spot at the start of the simulation. They differ only by 0.0001 units horizontally. For the first 23 seconds, the blue and yellow trajectories are the same, but then they start to diverge wildly. The centre cone in the chart below shows the position after 30 seconds.

The butterfly effect in the Lorenz attractor

Source: XaoBits, Wikimedia Commons

In their research, Jiang et al. demonstrated something like a butterfly effect in US stock markets. Whenever index funds put money to work in the market, idiosyncratic volatility for larger stocks increased more than for small stocks, and excess returns over cash increased as well.

But index flows into the US stock market are tiny. Over the last 25 years, they average 0.05% of US stock market cap per quarter with a standard deviation of 0.09% per quarter. Annualised, we are talking about 0.2% of market cap shifting from active to passive management per year.

They show that while the impact on the relative market cap of the largest stocks in the US is a tiny 0.3% per quarter, this accumulates over time. After 25 years these tiny shifts in market cap between larger and smaller stocks amount to large-cap stocks being 30.25% larger than they would have been without the rise of index investments!

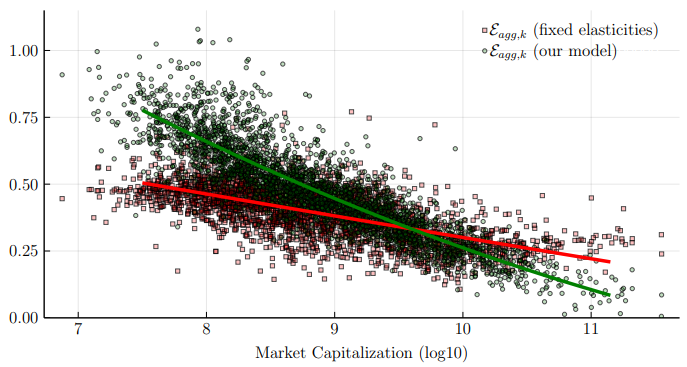

But why would the market cap of large stocks in an index react more than the market cap of smaller stocks? This is where Valentin Haddad, Paul Hübner, and Erik Loualiche provide a fascinating answer. They measure the price elasticity of stocks to changes in flows for each stock in the US. They find that the larger a company, the more inelastic demand becomes. But when demand is inelastic it means that a small increase in demand leads to a larger increase in price (and hence market cap).

The reason why demand becomes more inelastic for larger stocks is simply because almost every investor – whether active or passive – needs to own the largest companies in a market. If you own smaller companies, you can easily sell them when they become too expensive and in your view overvalued.

If you are an active fund manager, nobody will blame you for underperformance just because you didn’t own Etsy shares. But try not owning NVIDIA or Apple shares and then underperform the market and see how your investors will react… Hence, even active investors are forced to hold at least some NVIDIA and Apple shares no matter how expensive they are. And that tiny difference in demand creates a huge benefit for the largest stocks over 25 years.

Elasticity of demand declines for larger stocks

Source: Haddad et al. (2024)

Joachim Klement is an investment strategist based in London. This article contains the opinion of the author. As such, it should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of the author’s employer. Republished with permission from Klement on Investing.