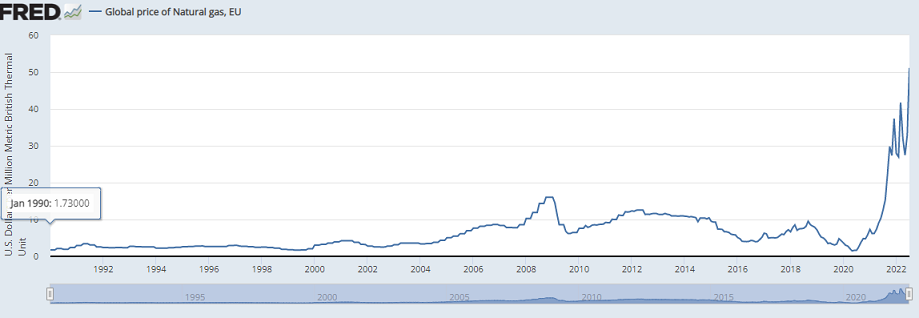

Europe is restarting mothballed coal-based power plants because the benchmark electricity price has exceeded 1,000% above its average of the past decade (where prices are set by the marginal cost of the last unit – essentially, the most expensive unit – of energy purchased to balance demand). Electricity prices are spiralling because the cost of natural gas, the marginal fuel in most European electricity markets, has soared 1,300% above its decade average. The shock would be like oil nearing US$550 a barrel.

Global price of natural gas, EU

Sources: IMF and Federal Reserve of St Louis. Found at: fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PNGASEUUSDM

Widespread controls

The EU, in response, is imposing wartime-like price controls, rationing and a windfall tax on energy companies. In the UK, the prospect of household energy bills jumping by 9% of GDP has prompted London to announce emergency measures worth double the cost of the pandemic furlough scheme, and to reallow shale-gas fracking.

Norway, where hydropower generates 90% of local needs, may curb the export of electricity, raising concerns cross-border flows could collapse across Europe. French nuclear power output is diving due to maintenance and repairs, with Électricité de France only operating 26 of the country’s 57 reactors. President Emmanuel Macron warns of the “end of abundance”. Germany is worried that rage over energy prices driving inflation to near-50-year highs could turn violent. Kosovo is facing two-hour blackouts every six hours, the first European country to display this feature of a failed state.

In China, daily hydro generation from the Three Gorges dam on the Yangtze River has dived 51%. Factories have suspended operations and cities are dimming lights. Japan is overcoming its Fukushima fears and returning to nuclear power. Southeast Asia is using coal to replace the liquified natural gas diverted to Europe. South Asia is suffering blackouts because energy is unaffordable. US natural gas prices in August breached US$10 per million BTU, a 400% increase on the recent years, due to demand from Europe.

The world faces its biggest energy crisis since the 1970s when soaring oil prices helped create the stagflation for which the decade is renowned. Today’s energy blow could be crueller because the energy industry, having overcome the pandemic disruptions that boosted prices for hydrocarbons, is beset by three challenges that are set to persist, if not worsen.

Three major challenges

The first challenge is the unfavourable state of global politics. Europe’s torment is due to the significant cuts to the supply of Russian oil and natural gas that accounted for 40% of its energy needs. Oil and gas prices are likely to stay elevated in the near term because the world’s energy system cannot quickly replace Russia’s lost hydrocarbons, which equate to about 10% of global energy production.

The Middle East is another concern. The return of Iranian oil to replace Russia’s missing barrels depends on restoring the agreement on Iran’s nuclear capabilities between Iran and the EU, Germany and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, one of which is Iran’s ally, Russia. Moscow could easily delay any new agreement or ensure that any restored pact is short-lived.

The second energy challenge relates to climate change. Droughts and heatwaves in China, Europe and North America are hampering hydropower electricity generation while boosting demand beyond capacity. France’s nuclear industry has cut production because receding rivers make it harder to cool reactors. The other angle to climate change is that renewable energy generation has not reached a level where it can compensate for lost fossil fuels.

The third challenge for energy markets is overcoming policymaker mistakes:

- The biggest error is that Europe, notably Germany, became dependent on Russian energy, especially natural gas that is not as easy as coal or oil to replace.

- A second mistake is France has failed to keep operational the country’s nuclear reactors.

- A third error, many would argue, is the world’s turn away from nuclear energy after the Fukushima disaster in 2011.

- A fourth blunder was not investing enough in renewables. Much blame will flow if the rising prices that are creating huge paper losses for utilities on Europe’s energy derivatives markets spark financial instability.

Reduction on living standards

Today’s energy crisis is still unfolding. In time, the promise of profit will calm the crisis with clean solutions that snap Western dependence on despots. In the meantime, however, the energy crisis is likely to cut global living standards, boost inflation, trigger a recession or worse in Europe, hound those in power, widen inequality within and between countries, trigger social unrest, spark industrial conflict and impede the fight against climate change. The damage inflicted just in Europe will likely make the 2020s energy crisis worse than that of the 1970s.

To be sure, favourable developments in relation to the Ukraine war could calm things and droughts will break and heatwaves pass. Maybe a sunny, warm and windy winter in Europe and energy substitution and conservation will ease power costs. Countries with gas and other energy reserves stand to gain. The recent fall in oil prices relieves inflationary pressures. But spot oil prices have declined on China’s pandemic lockdowns and concerns about a European recession.

The energy crisis largely created by Russia’s missing fossil fuels might best be viewed as shorthand for a series of crises around climate change, government finances, inequality, inflation, politics and social cohesion. Policymakers have much to solve before they can close for good those coal plants being refired to overcome today’s energy emergency.

Michael Collins is an Investment Specialist at Magellan Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is for general information purposes only, not investment advice.

For more articles and papers from Magellan, please click here.