As investing rules of thumb go, 'don’t put all your eggs in one basket' is widely accepted and uncontroversial. Sure, a lot of academic work has been done on the optimal number of baskets investors should have, what each basket should be made of, even the number of eggs to include in each, but the general principle is considered a sound way of spreading risk. And more baskets are better than fewer.

The problem with rules of thumb is that they can often oversimplify things. In average circumstances, simplification is usually enough, but right now, markets are anything but average.

There's more to diversification than 'more'

In the case of diversification, the difference between the rule of thumb and a more nuanced version lies in the gap between the expression more = better and more + different = better.

For a portfolio to be diversified it can’t just have lots of things in it, it needs to be filled with assets that are going to react in different ways to the same thing.

And, by that logic, we believe, the broad market is far less diversified right now than it looks on paper, especially if you are a passive investor.

Take the FTSE World Index, for example. Using the more = better version of diversification, an investment into an index that provides exposure to thousands of stocks across the globe should provide a good degree of diversification.

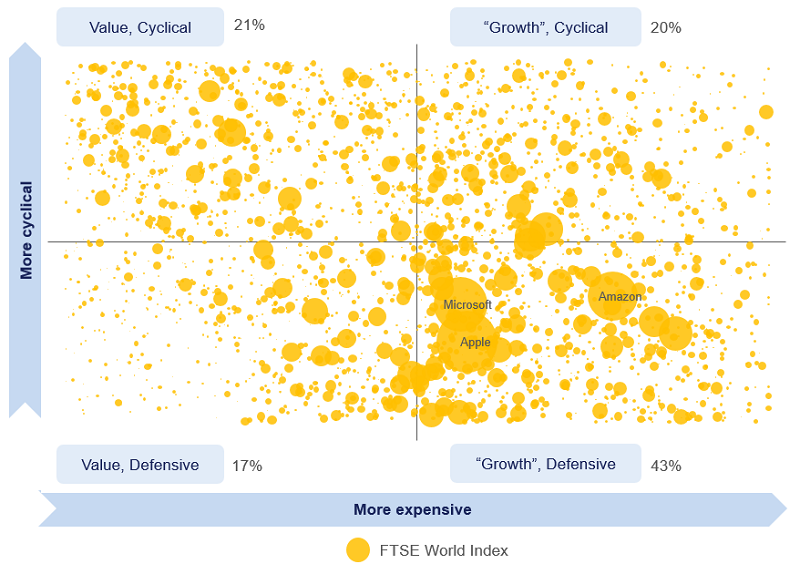

But, as is evident from the chart below, which plots the stocks in the FTSE World Index, with bigger positions shown as bigger yellow circles, the index is currently heavily weighted to defensive growth stocks (see the bottom right hand quadrant).

These include companies like Amazon and Netflix, with business models almost perfectly designed to benefit from the economic climate created by a global pandemic in 2020. Those conditions have propelled these 'lockdown beneficiaries' to rich valuations and to a colossal weight in the index. So much so, that defensive growth companies now account for over 40% of the index.

Under the microscope: FTSE World Index

As at 31 Dec 2020. Source: Various industry sources, Company information, Orbis. Statistics are compiled from an internal research database and are subject to subsequent revision due to changes in methodology or data cleaning. Stocks in the FTSE World Index are ranked based on their valuations (dividend yield, earnings yield, free cash flow yield and book to price; all based on trailing 12 month fundamentals) and their beta to a basket of global yields (as a proxy for cyclicality). Figures represent the aggregate weighting of shares within each quadrant for the FTSE World Index. Figures may not sum due to rounding. Bubbles representing the top three stocks in the FTSE World Index have been labelled.

Success creates sector bets

While there is no denying that many of the companies within the bottom right hand quadrant are of high quality, many are in similar sectors and are exposed to similar economic forces, which means they won’t necessarily do a good job of diversifying risk should economic circumstances or investor sentiment change.

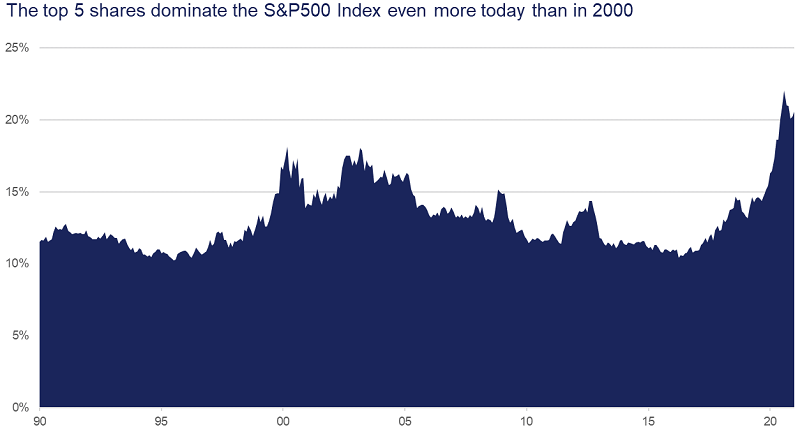

To put an even finer point on it, in the US market (S&P500 Index), the top five stocks now account for almost a quarter of the total. That is a level of concentration never seen before. At the height of the technology bubble in 2000 the top five accounted for less than 20% of the total.

As at 31 Jan 2021. Source: Refinitiv, Orbis.

Again, that is not to say that those five companies are bad, far from it. But rather, it points out that for every dollar invested into the broad S&P500 Index, roughly 25 cents is going into five technology stocks, all of which are in direct competition with each other in one way or another.

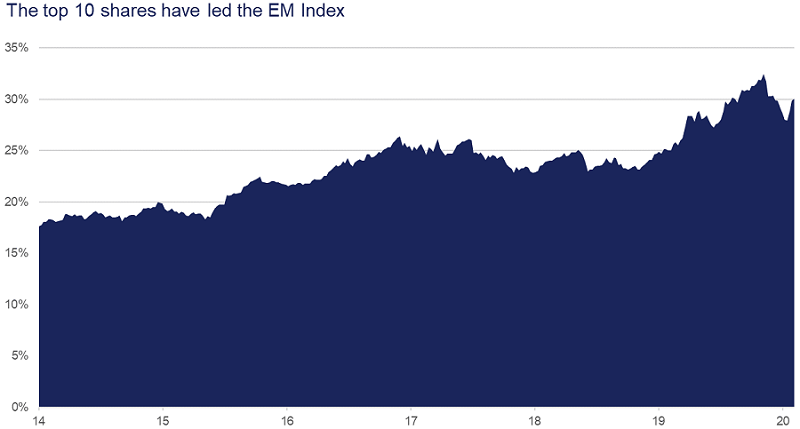

And, while the weight of the FANGAM stocks get the headlines, the extreme concentration seen within indices currently is not limited to developed markets. In fact emerging markets are arguably even more concentrated.

Within the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, the top 10 stocks currently account for over 30% of the total, approximately double their weighting five years ago.

As at 31 Jan 2021. Source: Refinitiv, Orbis.

As long-term, active, fundamental investors, we are no strangers to concentrated portfolios, in fact we are a firm believer in their ability to deliver outsized returns over the long run.

But, we build them intentionally from the bottom up. As we look across global markets today, that intent seems to be lacking, replaced by a fear of missing out that is leaving a lot of eggs in one very small basket. A basket predicated on the notion that the future is going to look very similar to the recent past. And, what we have learned over the past 30 years, is that the only thing we can say for certain about the future is that it seldom looks like the past.

Shane Woldendorp, Investment Specialist, Orbis Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This report contains general information only and not personal financial or investment advice. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or individual needs of any particular person.

For more articles and papers from Orbis, please click here.