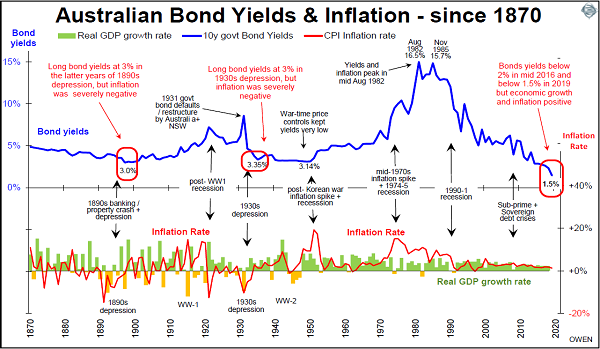

Yields on Australian government bonds have continued falling this year. At the end of May 2019, the 10-year bond dipped below 1.5%, the lowest in history. Yields on 10-year government bonds peaked at an incredible 16.5% in mid-August 1982 and have been declining (along with inflation rates) ever since.

The chart shows bond yields, inflation and economic growth rates in Australia since 1870.

What do low bond yields tell us?

As bond yields represent the market’s collective view on the outlook for economic growth and inflation, the current ultra-low yields are extremely pessimistic. Yields are now lower than in the depths of the 1890s depression and the 1930s depression, when economic growth and inflation rates were deeply negative.

But since economic growth and inflation are positive now, why are yields so low?

Click to enlarge

At first sight, it appears that the current all-time low yields are a sign that ‘the market’ is expecting worse outlooks for growth and inflation than in the 1890s depression and the 1930s depression. However this is misleading. Prior to the 1990s Australia was regarded as a high risk ‘emerging market’ and so yields on bonds were higher to reflect a higher risk of default. Indeed the Commonwealth government defaulted on its entire stock of domestic bonds in 1931 (having taken over responsibility for the State debts, and in particular the defaulting NSW). Australia only regained respectability in international credit markets after the long post-WW2 boom which allowed the debt to be repaid, and after the reforms in the 1980s including dismantling tariff barriers, privatisation, deregulation, and floating the dollar.

Australia’s good standing in credit markets now partially explains the lower overall level of yields in the past few years compared to the prior 100 years.

But yields are too low

Even allowing for this change in status of Australia as a credit-worthy borrower, the current yields are still far too low. Australia may be heading for a local slowdown and possibly recession in the coming year or so, but the current yields are suggesting we should expect virtually zero growth and inflation for the next decade. This is far too pessimistic for a country with the fastest growing population, the most favourable demographics, the lowest government debt levels in the developed world, strong public institutions and a stable government.

The main reason for the low yields is that most Australian government bonds are owned by foreigners scouring the world for yield, and Australia is one of the very few countries left with a ‘AAA’ credit rating. Australian yields may be low relative to our history, but they are still higher than many other countries.

Japanese and German yields are still negative thanks to years of massive central bank ‘quantitative easing’ bond-buying programmes. UK yields are not far above zero, and French and Spanish bonds are below 1%. Australian yields are now even lower than in Canada. Canadian yields are being kept relatively high by the close links to the US, where the economic recovery boosted by the Trump tax cuts has kept US yields above 2% since their post-Brexit lows in 2016.

What does this mean for investors? Although we believe Australian yields will rise in the medium term, we have significant allocations to Australian bonds in portfolios as we had been expecting yields to fall in the short term. The declining yields generated above-average returns of around 6% for 2019 to date (and they beat shares by 8% in 2018). Not bad for boring old bonds in a so-called ‘low return world’.

For borrowers, it will probably mean we heading into a period when fixed rates on loans are the lowest we will see for many decades.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.