Affordable housing plays an important role in the welfare of lower income households. Yet spiralling house prices in recent years and the limited supply of quality affordable housing is placing significant pressure on these households.

The affordable housing problem needs urgent attention. In 2013-14, approximately 31% (2.7 million) of Australian households were in the rental market. Around 47% (1.3 million) of these were classified as lower income households (ABS). According to the Productivity Commission, in June 2015 there were about 190,000 households on the waiting list for social housing, of which about 66,000 were deemed to be of ‘greatest need’. Social housing costs state and federal budgets more than $10 billion per year.

A major step forward in addressing affordable housing supply recently occurred when the federal and state treasurers agreed to the recommendations of the Affordable Housing Working Group (AHWG) at the Council on Federal Financial Relations (CFFR).

Alternative financing models

The AHWG was charged with investigating innovative financing models aimed at improving the supply of affordable housing, with a particular focus on models that attract private and institutional investment at scale into affordable housing. The AHWG canvassed four possible innovative finance models:

- a housing bond aggregator (see below)

- a housing trust

- housing co-operatives

- social impact investing bonds.

The AHWG took 78 submissions from interested parties including community housing providers, banks and welfare agencies, the majority of which advocated a housing bond aggregator as a priority.

It’s not surprising then that their key recommendation was the establishment of a financial intermediary to aggregate the borrowing requirements of affordable housing providers and issue bonds on their behalf (the bond aggregator model). The AHWG argues that the bond aggregator model “offers the best chance of facilitating institutional investment into affordable housing at scale, subject to the provision of additional government funding.”

By providing cheaper and longer-term finance for community and affordable housing providers, the AHWG believes this model has several benefits:

- it enables affordable housing providers to refinance their existing borrowings and finance new developments at lower cost and longer tenor

- it creates a market for private affordable housing investment that both normalises and expands capital flows to the industry

- it best addresses the barriers of return and liquidity by providing an instrument that is understood by sophisticated investors as a fixed income investment

- due to its financial profile, it can be easily traded in a secondary market and would be seen as an attractive low-risk financial product.

The UK offers a template

The bond aggregator model has been successfully implemented in the United Kingdom. The Housing Finance Corporation (THFC) has, for more than 30 years, been on-lending predominately long-term debt, obtained from bond issues (public issuance and private placements) and bank loans including funding from the European Investment Bank to over 150 individual housing associations throughout the UK.

THFC has an ‘A’ credit rating from Standard and Poor’s and a total loan book of more than £4.2 billion.

How would a housing bond aggregator operate?

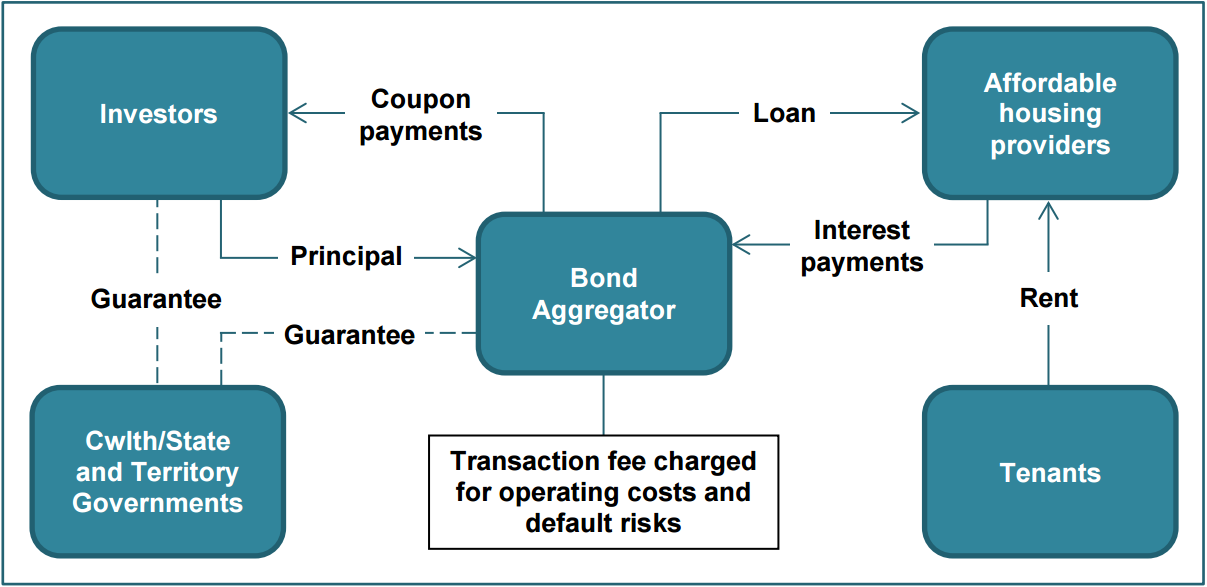

A housing bond aggregator model requires the establishment of a specialist financing intermediary, whose function would be to liaise with affordable housing providers to determine the amount of debt they are seeking to raise. The intermediary, or entity acting on its behalf, would then source these funds in aggregate from wholesale markets by issuing bonds to investors. The funds generated would then be loaned to the relevant housing providers in return for ongoing interest payments (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A Housing Bond Aggregator Model

Source: Affordable Housing Working Group

The design of any bond issued to finance affordable housing will be critical. The AHWG identifies four key items that would need to be decided upon:

- the type of bond and its coupon payment (fixed or indexed to inflation)

- the term of the bond (between 25 and 40 years would best match the lifespan of housing investments, however Australia has traditionally had a much shorter tenor bond market)

- the loan to valuation or interest coverage ratios used for lending purposes

- whether any government guarantee is provided, as well as which level of government issues the guarantee, the size of the guarantee and whether it is transitional or ongoing.

Can house bonds have an impact?

The simple answer is yes. How much depends on the demand for credit by affordable housing providers and the appetite of institutional investors. The AHWG estimates that if the bond aggregator simply allows the refinancing of the existing debt of community housing providers (estimated at over $1 billion) at cheaper rates it could result in an increase in their borrowing capacity by over 65% or an additional $765 million. If this amount was to be reinvested into new affordable housing it could fund the construction of up to 2,200 new dwellings, assuming an average dwelling cost of $350,000 and no increased equity requirements.

The AHWG also acknowledges that the bond aggregator can’t solve the affordability problem entirely. It notes the importance of a variety of complementary reforms, including nationally consistent regulation of community housing providers, planning and zoning regulations, and taxation and concessions.

While there is some way to go, the signs are encouraging. The treasurers at CCFR agreed to the establishment of a taskforce to design the exact mechanism and report back to the heads of treasuries by mid-2017.

Adrian Harrington is Head of Funds Management at Folkestone and one of the Federal Government’s representatives on the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).