Countless articles have been written on Brexit, but most focus has been on the immediate panic selling after the vote. This commentary adds more context to the debate.

Britain’s long history of trading with Australia

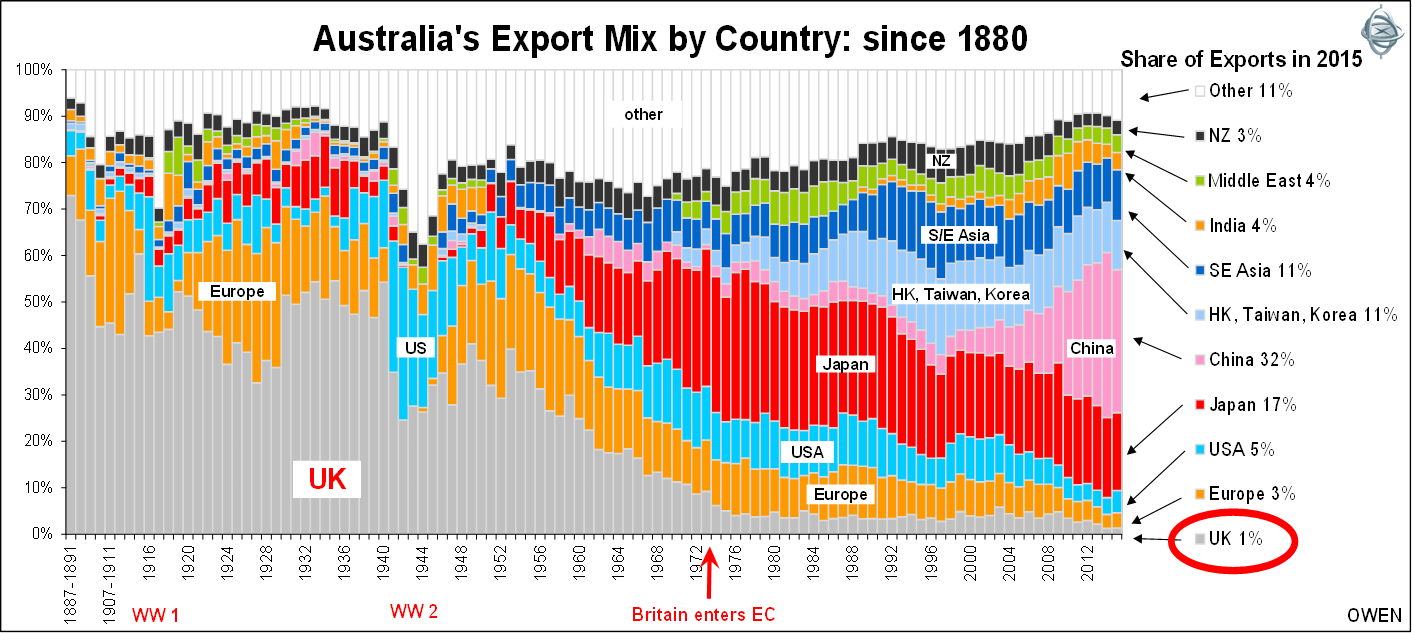

As a British colony, Australia was heavily reliant on Britain for investment capital and export revenue. Prior to Federation in 1901, Britain bought virtually all of our exports (mainly wool and gold), making Australia one of the richest countries in the world per capita.

Britain remained our largest export partner until 1940, when it fell to second behind the United States. After the War our export mix changed dramatically, playing a vital role in the reconstruction and reemergence of Europe and Japan. By 1967, Japan’s hunger for our iron ore and coal made it our largest export partner, remaining in that position until it was superseded by China in 2010.

The chart below shows the declining role of Britain in Australia’s export revenues since the 1800s.

When Britain entered the European Community in 1973, it dismantled its preferential access system for former colonies such as Australia. By that time, however, its impact was relatively minimal given that Britain was buying less than 10% of Australian exports. This was less than the percentage of our exports going to Europe, and less than a third of what Japan was buying. Today, Britain accounts for just 1% of Australia’s export market.

Where to from here?

Britain was a late entrant into the European Community and never adopted the Euro. What was surprising about the Brexit vote, however, was the way in which voters rejected the pleas from both major parties to remain. The final result defied opinion polls taken in the days and even hours before the vote.

This surprise may explain the knee-jerk reaction of financial markets. Globally, ‘risk assets’ like shares, high-yield bonds and commodities (with the exception of gold) were gripped in a wave of panic selling. The money went into ‘safe havens’ such as cash, government bonds and gold.

Markets have since calmed, leaving investors to digest what it all means. The implications for Britain in the long term may well be benign or even positive. An exit would remove a seemingly unnecessary layer of bureaucracy that interferes with every aspect of daily life and costs tax-payers money. In addition Britons will win back some control of immigration, which was the catalyst for the sudden upsurge in dissatisfaction with Europe’s open borders policy. This renewed sense of independence and self-determination may boost spending, investment and employment.

Britain has always been a major source of investment capital for Australia and this may well increase if the Brexit proceeds. The impact of a British exit on trade should be minor in the medium to long term. As Europe accounts for half of British trade, the lower pound will help British exports. The pound fell 10% against the Euro after the vote, and is down 17% since this time last year. But it is still 5% higher than where it was three years ago, so it may need to fall considerably further to provide any real benefit for British exporters.

A more likely impact will be on British companies that operate in Europe under the EU passport system that allows firms to function across the EU without extra licensing in each country. Obtaining new licences should not be a problem for most companies but there will be inevitable disruption in the transition. Some very successful economies operate in Europe outside the EU, like Switzerland and Norway.

Fragmentation may accelerate

While Britain negotiates new treaties, short-term disruption and uncertainty will probably cause an economic slowdown and it may also slow growth rates in Europe, which has been stagnant since the GFC. The Brexit may also accelerate the end of 'Great' Britain. Scottish and Northern Ireland voters overwhelmingly voted to remain in the Union, leading to renewed calls for Scottish independence and the reunification of Ireland.

Another result of the vote is that it may accelerate fragmentation of the EU and Eurozone. It will certainly embolden anti-EU parties across the continent and there are already movements in France (Frexit) and the Netherlands (Nexit). It may also provide more impetus to internal independence movements such as Catalonia in Spain, Flanders in Belgium, Basque in France, and many others. Further political unrest could delay investment spending, leading to slower economic growth and higher unemployment.

More worrying is if the Brexit is seen as a backward step in the globalisation of trade and investment. The European experiment was undoubtedly good for the European recovery after World War 2, but since the GFC we have seen increasing signs of protectionism and currency wars between the big players – the US, China, Japan, and Europe.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at independent advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities.