Introduction

My economics degree at UNSW spanned four years of the 1970s, a time when monetary policy - the cost and availability of money in the economy - was an influential theory. Leading monetarist Milton Friedman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1976 and The Economist called him "the most influential economist of the second half of the 20th century ... possibly of all of it".

When I started working in investment markets in 1979, the release of money supply data such as M2 was a major economic indicator watched by financial markets. But as the years went by, focus switched to other data points such as unemployment, inflation, GDP growth and trade accounts and most people ignored money supply.

When March 2020 and Covid-19 arrived, and central banks around the world adopted unlimited measures to stimulate economies with low interest rates, liquidity by the trillion and free loans, nobody was watching the elephant in the room. I had been schooled in monetary policy implications and it always nagged me that the theories and policies that guided governments for decades now seemed irrelevant.

Not for Professor Tim Congdon, Chair of the Institute of International Monetary Research. Firstlinks issued his warnings about inflationary consequences of loose money as early as April 2020. This is not looking back with hindsight, here are two of Congdon's articles with a couple of extracts:

Magic money printing and the reality of inflation, Tim Congdon, 15 April 2020

"What is wrong with the supposed ‘magic money tree’? The trouble is this. When new money is fabricated ‘out of thin air’ by money printing or the electronic addition of balance sheet entries, the value of that money is not necessarily given for all time. The laws of economics are just as unforgiving as the laws of physics. If too much money is created, the real value of a unit of money goes down ... The Federal Reserve’s preparedness to finance the coronavirus-related spending may prove suicidal to its long-term reputation as an inflation fighter ... If too much money is manufactured on banks’ balance sheets, a big rise in inflation should be expected."

How long will the bad inflation news last?, Tim Congdon, 9 June 2021

"Further, [Jay Powell's] research staff have evidently failed to explain to him that a monetary explanation of national income and the price level – in which inflation is determined mostly by the excess of money growth over the increase in real output – has a long and distinguished pedigree in macroeconomics."

Central banks, including our own Reserve Bank, thought inflation would be minor and transitory, and Governor Philip Lowe's relaxed statements about no rises in cash rates until 2024 are now part of financial markets folklore.

Congdon has recorded a new video, and below is an edited transcript with my bolded emphasis. Showing how the world again ignores his pleas, this video has been viewed only 1,500 times on youtube. Influencers receive more than that for boiling an egg or fitting a door. In case readers do not make it to the final sentence, here is Congdon's scathing conclusion.

"I want just simply to warn you that this so-called profession of economics is a disgrace. What's happened in the last two or three years is shocking. The increase in inflation is the result of excessive money growth that was due to the things done by governments and central banks in spring and summer of 2020 above all. All these other theories about corporate greed, and profiteering, and the need for immigration are a lot of rubbish."

***

Tim Congdon: It's the start of 2023 and people are interested in forecasts for the year. So, what I want to do is to explain some of the implications of developments in money growth and banking systems for the macroeconomic prospect. I'll also say a few things about the analytical basis of the whole exercise. I'll finish by pointing out four incorrect approaches to inflation, also say one or two things about Paul Krugman's commentary on the world.

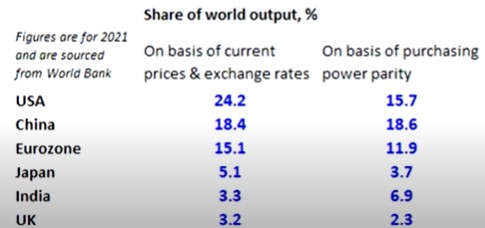

So, we're talking about where the world economy is going in 2023. Let's look at the relative importance of the main economies.

You can see that the United States and China have the world's two largest economies. The relative importance depends on the way in which we assess the size of the economy. And you can see that both of these economies are very important to the world outlook. The Eurozone by itself is quite a bit less important than either China or the USA. Japan comes next, and then I've also included India and the U.K. The U.K. is now relatively unimportant compared with the rest of the world, of course. India has overtaken the U.K. in terms of GDP in current prices and exchange rates and in terms of purchasing power parity is really quite important.

What does the Institute add to the various pieces of commentary that you see around? We add the monetary perspective. We've argued over the years that money is basic to the inflation prospect. The key lines of analyses in all this are, first of all, that over the medium term, the growth rates of money and nominal GDP are similar. By money, I always mean a broadly-defined measure of money which is dominated by bank deposits, so behavior of the banking system is crucial. The increase in nominal GDP in turn is split between the increase in real output and the increase in prices. So, the behavior of money gives us insight into the future behavior of inflation. That's the key analytical framework that I use.

Money growth in major countries

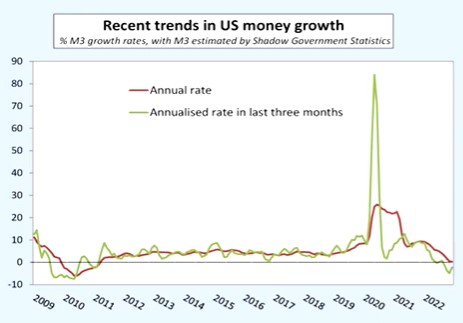

We'll start off with the United States.

You can see here the extraordinary rapid growth of money in 2020. The Institute warned straight away in spring 2020 that this would lead to inflation. We have been correct about that. The analytical framework in that sense has been vindicated. Now, what's happening at the moment is quite the opposite of that. In fact, towards the end of last year, the quantity of money actually fell in the USA, and with inflation at much higher rates than the rate of money growth, real money balances, money balances adjusted for inflation actually went down very sharply, which is a classic leading indicator of recession.

Now we have had weak asset prices in the USA, but we haven't really had any real sign of beneath trend growth of demand and output as yet except, say, in the housing market. All the same, I would insist that the prospect in the USA in the middle and towards the end of 2023 is for beneath trend growth.

China is not like the other countries in this discussion. The rate of growth of money was rising through 2022, maybe just coming off the boil in the latest month, but that's just a wobble as yet. The rate of money growth in China was rising through 2022. I've just shown that China has got the world's largest economy, roughly speaking, with the USA. It's a very big importer, larger exporter than the USA. And this therefore has got quite important implications to world economy.

There have also been astonishing announcements about future policy from China in the last few weeks, which almost amount to a complete reversal of what was going on for most of Xi Jinping's period as the leader of China. We're just speculating about what they really mean, but they seem to indicate a move back towards opening up the economy towards more friendship with the West. But I think a fair verdict is that China will actually have above-trend growth in 2023. Trend growth may have fallen sharply down to, say, 3% or 4% a year, not like the old 10% plus we had in the hyper-growth period for China. But Chinese developments will be positive for world economy in 2023, unlike what's going on in the main Western economies, which are struggling with inflation.

The story for the Eurozone and the U.K. is that they too had these bursts of rapid money growth in 2020, policy response to COVID. And then, there's been this fall away, but it's less marked in the Eurozone and the U.K. than in the United States. I think the message is that the Eurozone and the U.K. will both have recessions in 2023, and probably they will make less progress on inflation in 2024.

(in the video, Congdon also discusses Japan and India at about the 9 minute mark but for this audience, we will remove the text).

So, let's just try and bring that together. I think we're talking about falling output, of weak demand in most of the big Western economies – USA, Eurozone and Japan, and the U.K. By contrast, in the big Asian economies, and indeed much of the rest of Asia, the continent that really matters to the world economy, the prospect is actually for resilient and possibly even above-trend growth in demand and output.

So, for the world as a whole, I would expect output to carry on growing in 2023 despite the weaknesses in the western economies, inflation coming down generally. And in 2024, it's quite conceivable, given the severity of the current monetary contraction in the USA, that there will be inflation back towards the 2% figure. I think the message is a little bit more cautious on that front in the Eurozone and the UK.

Well, this is all inside a framework in which money drives nominal GDP. And because real output in the end is driven by other things such as technology, demographics and so on, the excess of money growth over output determines inflation. It's all within the context of the monetary theory of inflation. In my view, the evidence for that theory is overwhelming, both in the recent past and over many decades of experience when we have the good data to establish these facts.

Other theories on the cause of inflation

However, in commentary on the last two or three years of this rather shocking inflation episode, there have been a number of other theories going around.

The first one is that inflation is caused by social conflict. It's the idea that trade unions demand higher wages that pushes up costs and that pushes up inflation. And so, social conflict is the source of the trouble. Some statement on these lines has been made in the last few weeks by Olivier Blanchard who used to be chief economist at International Monetary Fund.

"Inflation is fundamentally that the outcome of the distributional conflict between firms, workers and taxpayers. It stops only when the various players are forced to accept the outcome."

No reference to money there. And in fact, you might think that inflation is really a matter for sociologists, not economists. But there we are.

Second, there's a similar point of view, just a little bit different, which argues that corporate greed is the cause of inflation. In other words, companies push up prices to widen their profit margins, and this then leads to wider process of inflation. This sort of view has been stated in the last year or two in the United States of America by, for example, a chap called Robert Reich who used to be the US Labor Secretary, and he said that the inflation is caused by this profiteering, price gouging, and indeed, that it should be really countered by prices and incomes policies. There's even been a bit of a debate between President Biden and Jeff Bezos. So, there's those theories that need to be looked at – social conflict, corporate greed.

There's then a third point of view that rising wages are the trouble. It reflects what's happening in the labor market, there's shortages of workers. So, the answer is more immigration. And this proposal has been made in a recent article in the Foreign Affairs Journal by two authors called Gordon Hanson and Matthew Slaughter.

And then, the last theory I want to review is this idea that the reason that the world had low inflation in the 1990s and then again in the 2010s was because of so-called China effect, that globalisation meant that cheap imports were coming in from China, in particular, other countries as well, and this is holding down the price level and leading to low inflation. More generally, that globalisation was the key to the explanation of low inflation and deglobalisation will cause rising inflation.

So, those are the theories that I want to review in future videos. I regard all of them as wrong, all of them as dangerous. The correct theory is the monetary theory.

Clear warnings were ignored

Let me finish by saying that it's really been quite a battle with these ideas for the last two or three years, I'd say, for a longer period, and I really must protest about the kind of thing that's being said about monetary analysis.

At the start of this process of the current inflation episode back in March-April 2020, I gave very clear warnings that rapid money growth would lead to inflation. There were many other economists at the time who said nothing of the sort, and one of them was Olivier Blanchard, the former Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund. And let me just quote to you what he said in in April 2020 (sourced in the video).

"This column argues that it's hard to see strong demand leading to inflation. The challenge for monetary and fiscal policy is thus likely to be to sustain demand and to avoid deflation rather than the reverse."

He was utterly wrong. Now, to give Blanchard and people like Larry Summers and so on their due, they were then indeed a year or 18 months later saying that there was going to be an inflation problem, but not because of rapid monetary growth, by the way.

But they were battling with a chap called Paul Krugman, the world's most influential economist, a writer on the New York Times, who led something called Team Transitory, that inflation is going to be transitory. This kind of thing that was also spouted by most of the main central banks. In one sense, although they were 18 months late, Blanchard and Summers were right, but let's just be clear that they had been totally wrong at the start of 2020.

We then get Krugman in a column just a few weeks ago saying that Blanchard had basically been right. He hadn't been. Here's Krugman on Blanchard, this is a column of The Football Game Theory of Inflation, January 3rd (The New York Times):

"Several prominent economists carried on a thoughtful, earnest online debate about inflation over the past weekend. The discussion was kicked off by Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (a towering figure in the profession, who happens to be one of the economists who has gotten recent inflation more or less right)."

I've just shown you, he was completely wrong. In May 2021, people were rethinking this matter, not really because of money growth and money trends and the kind of thing I was saying, but just simply because of what was happening to commodity prices, wages and the economy.

And this is how Paul Krugman characterised me and other people. He said we were cockroaches (NYT 13 May 2021). He said:

"And lately I’ve been noticing an infestation of monetary cockroaches. In particular, I’m hearing a lot of buzz around how the Fed’s wanton abuse of its power to create money will soon lead to runaway inflation."

Look, even by then, it was clear money growth was slowing down a bit, there wouldn't be runaway inflation, but there would be a serious inflation episode and I said so.

Anyway, I'll finish there. I want to warn you that this so-called profession of economist is a disgrace. What's happened in the last two or three years is shocking. The increase in inflation is the result of excessive money growth that was due to the things done by governments and central banks in spring and summer of 2020 above all. All these other theories about corporate greed, and profiteering, and the need for immigration are a lot of rubbish.

This is an edited transcript of the video: IIMR January 2023 video: 'Money trends and the global macro outlook at the start of 2023'. T Congdon.

Professor Tim Congdon, CBE, is Chairman of the Institute of International Monetary Research at the University of Buckingham, England. Professor Congdon is often regarded as the UK’s leading exponent of the quantity theory of money (or ‘monetarism’). He served as an adviser to the Conservative Government between 1992 and 1997 as a member of the Treasury Panel of Independent Forecasters. He has also authored many books and academic articles on monetarism.

This article is general infomration and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.