“Anyone who thinks there’s a formula for investing that guarantees success (and that they can possess it) clearly doesn’t understand the complex, dynamic, and competitive nature of the investing process. The prize for superior investing can amount to a lot of money. In the highly competitive investment arena, it simply can’t be easy to be the one who pockets the extra dollars.”

- Howard Marks, Founder, Oaktree Capital

“Markets and economic movements are driven by much simpler and more common sense linkages than most people articulate.”

- Ray Dalio, Founder, Bridgewater Associates

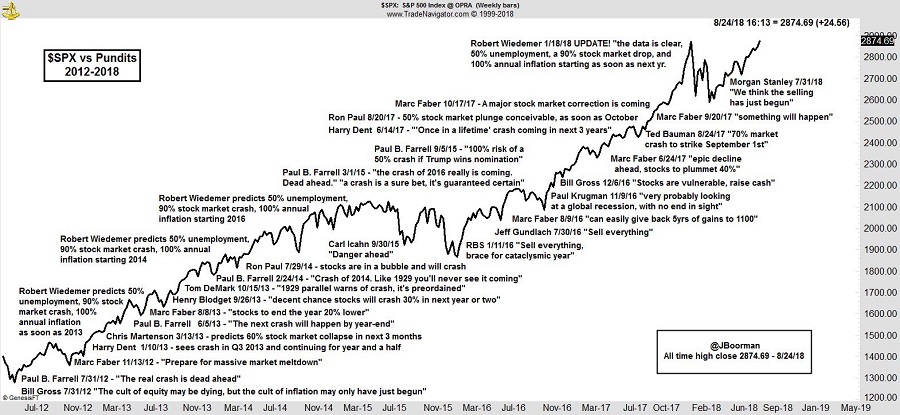

Stock and bond markets have a habit of making experts look foolish. At any point in time, for every expert who calls a market bottom, another says wait a year. One of my favourite charts, which was regularly updated by US analyst, Jon Boorman, before his death in 2020, is shown below. He highlighted the profound announcements of prominent 'pundits' and their "crash is coming" advice. I remember well starting 2016 with RBS's "Sell everything, brace for a cataclysmic year" before one of the best market run ups in history.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Who should investors believe when there are so many opinions, or is forecasting a fool's errand? Is good investing simply common sense or does success need deep and complex analysis?

Unfortunately, the only investors who are confident enough to ignore the short-term noise of expert predictions are the genuine long termers who set up their portfolios for decades and shut out the swings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Most people cannot avoid some form of active asset allocation, even if it is only deciding what to do with cash flows or how to rebalance as markets move.

Checking in on Dalio and Marks

While it's possible to make a billion dollars or so based on luck and personality rather than skill, it's more likely that some market experts who have spent decades accumulating significant wealth in the market probably have good reasons for their success.

At this transition point in markets, where a long cycle of falling rates and a decade of easy money are replaced by a tightening, let's check the latest from two billionaires who deserve more attention than most. Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio and Oaktree’s Howard Marks seem genuinely eager to share their expertise regularly in thought-provoking newsletters.

Something more fundamental than their latest market views struck me in their recent briefings. Dalio thinks investing is simple, common sense stuff. Marks calls it complex, competitive and convoluted. Who's right, or are they both?

Ray Dalio on common sense

Ray Dalio writes a regular newsletter on LinkedIn called ‘Principled Perspectives’ which gives his: “ongoing flow of research and perspectives about the economy, markets, life and work.” Sounds like an expert to me, but here he is on 22 June 2022:

“For me, hearing supposed ‘experts’ talk about what’s now happening in the markets and economy is like listening to nails scratch against a chalkboard because they are typically saying incorrect things in an erudite rather than common sense way. Markets and economic movements are driven by much simpler and more common sense linkages than most people articulate.”

There is some irony that Dalio criticises 'experts’ when he seems to aspire to be president of the club. Regardless, Dalio’s 'common sense’ thinking about inflation clears the air (and the bolding below is Dalio’s own).

“More specifically, I now hear it commonly said that inflation is the big problem so the Fed needs to tighten to fight inflation, which will make things good again once it gets inflation under control. I believe this is both naïve and inconsistent with how the economic machine works.”

The Fed has plenty of critics at the moment, but Dalio argues ‘naïve and inconsistent’ comes from not understanding the simplicity of supply and demand. He continues:

“That’s because that view only focuses on inflation as the problem and it sees Fed tightening as a low-cost action that will make things better when inflation goes away, but it’s not like that. The facts are that: 1) prices rise when the amount of spending increases by more than the quantities of goods and services sold increase and 2) the way central banks fight inflation is by taking money and credit away from people and companies to reduce their spending.”

Dalio thinks central banks should:

"1. Use their powers to drive the markets and economy like a good driver drives a car - with gentle applications of the gas and brakes to produce steadiness rather than by hitting the gas hard and then hitting the brakes hard, leading to lurches forward and backward.

2. Keep debt assets and liabilities relatively stable and, most importantly, not allow them to get too large to manage well.

To do this they should not allow interest rates and availabilities of money to be either too good or too bad for the debtors or the creditors. By these measures central banks policies have not been good … there isn’t anything that the Fed can do to fight inflation without creating economic weakness."

A month later, 13 July 2022, Dalio gave a further warning:

"I believe that we are in a paradigm in which the buying power of financial assets will go down because of a combination of 1) actual price declines when money is tight and 2) inflation when it’s loose. One of my investment principles that is very relevant now is "don’t always bet on up." Always betting on up, which is what almost everybody does, is both a mistake for investors and damaging to the economic system ...

What should an investor do in light of all this? Rather than always betting on up, every investor should look at how to diversify one’s portfolio to have some investments that go up when others go down which, if done well, reduces risks more than it reduces returns. While there are sometimes when even a well-diversified portfolio of assets will go down, it won’t go down as much as an undiversified portfolio, and it won’t stay down because a severe and extended period of bad performance is intolerable.

To Dalio, it’s common sense. The Fed should make only gentle changes to policy to guide the economy and investors should maintain a diversified portfolio. Of course, Dalio did not build the largest hedge fund in the world based only on ‘common sense’, and indeed, he is now passing on the principles behind his success. But his most-quoted life principle is relatively simple:

“Logic, reason, and common sense are your best tools for synthesizing reality and understanding what to do about it.”

Howard Marks on uncommon sense

Howard Marks believes a successful investor must think differently. Far from talking about ‘common sense’, his subtitle for his most famous book, ‘The Most Important Thing’, is ‘Uncommon Sense and the Thoughtful Investor”.

To Marks, investing is difficult and far from ‘first-level’, superficial thinking. He writes in his latest memo to clients:

"If you hope to distinguish yourself in terms of performance, you have to depart from the pack. But, having departed, the difference will only be positive if your choice of strategies and tactics is correct and/or you’re able to execute better.”

He then describes the need for ‘second-level thinking’. Beating the market is difficult and winners must be a step ahead. He says:

“Your thinking has to be better than that of others – both more powerful and at a higher level. Since other investors may be smart, well informed and highly computerized, you must find an edge they don’t have.”

Complex and convoluted

The way investors think is crucial to Marks, and it’s a long way from common sense:

“First-level thinking is simplistic and superficial, and just about everyone can do it (a bad sign for anything involving an attempt at superiority). All the first-level thinker needs is an opinion about the future, as in 'The outlook for the company is favorable, meaning the stock will go up.'”

Second-level thinking is deep, complex, and convoluted. The second-level thinker takes a great many things into account:

- What is the range of likely future outcomes?

- What outcome do I think will occur?

- What’s the probability I’m right?

- What does the consensus think?

- How does my expectation differ from the consensus?

- Is the psychology that’s incorporated in the price too bullish or bearish?

- What will happen to the asset’s price if the consensus is right or I’m right?

Not much simple, common sense in there.

“First-level thinkers look for simple formulas and easy answers. Second-level thinkers know that success in investing is the antithesis of simple.”

Marks says we can’t know much about the short-term future beyond the consensus view. Investors do not improve their performance by jumping in and out of the markets to avoid short-term problems and investors should aim for the benefits of long-term compounding. Here’s a big point:

“Even if we think we know what’s in store in terms of things like inflation, recessions, and interest rates, there’s absolutely no way to know how market prices comport with those expectations. This is more significant than most people realize. If you’ve developed opinions regarding the issues of the day, or have access to those of pundits you respect, take a look at any asset and ask yourself whether it’s priced rich, cheap, or fair in light of those views. That’s what matters when you’re pursuing investments that are reasonably priced.”

Short-term focus is a harmful distraction, and even if an investor is correct about an event, how much is already factored into prices?

Common sense versus uncommon sense

Warren Buffett says, "Investing is simple, but it's not easy". He reminds first-time investors that investing looks easy but it's actually difficult. He also said:

“None of the top 20 highest valued companies from 1989 are in the same list 30 years later. It is a reminder of what extraordinary things can happen.”

At one level, Dalio and Marks could be saying the same thing. Common sense - ignoring noise, investing for the long term, ignoring bubbles and hype - is not necessarily common. It's difficult to stick to a plan, and so perhaps, common sense is uncommon.

But the differences between Dalio and Marks run deeper and are more profound. Dalio has developed a set of principles which he describes as simple and common sense, as in anyone can learn them.

Marks' guidelines for success can be mastered by relatively few. He says:

"The difference in workload between first-level and second-level thinking is clearly massive, and the number of people capable of the latter is tiny compared to the number capable of the former. First-level thinkers look for simple formulas and easy answers. Second-level thinkers know that success in investing is the antithesis of simple."

I'm in the Marks camp. There are relatively few fund managers and expert investors who give unique insights and consistently deliver outperformance over their benchmarks through time. While it's easy to invest, it's difficult to be better than a lot of other smart people out there.

Graham Hand is Editor-At-Large for Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.