Thursday 7 November 2013 was a good example of the often perverse relationship between economic growth, company earnings and share prices, and also an example of how markets react to unexpected news in unexpected ways.

In theory, improving prospects for economic growth and company earnings should be good for share prices, while deteriorating prospects should be bad. Nice theory, but not in the real world, whether we are talking about daily, monthly, quarterly or even yearly time periods.

Expected versus unexpected

In the case of the relationship between news and share prices, expected news - like expected profits, dividends, economic numbers or interest rate changes, etc - is generally already factored into prices every day so it is unexpected news that causes prices to jump up or down sharply.

For example, if the market consensus is expecting a particular company to announce a 20% profit rise next Tuesday and it does in fact announce the 20% profit rise, then the share price will not jump up on Tuesday. But if for some reason the company announces flat profits on Tuesday the share price will most likely fall significantly (all else being equal) even though profits have not fallen.

Thursday 7 November 2013 was a good example of these factors at work in real life. There were two significant pieces of unexpected news that affected global markets.

European Central Bank rate cuts

The European Central Bank unexpectedly cut the refinance rate by 0.25% to 0.25%, and the emergency bank borrowing rate was cut by 0.25% to 0.75%. European Central Bank President Mario Draghi also said that the ECB still maintained an easing bias, meaning more rate cuts were possible.

This was a big deal as it represented a change in policy stance and a change in the dynamics of the tussle between the hard line pro-austerity ‘north’ led by the Germans and the pro-growth, anti-austerity ‘PIIGS’ led by France and the International Monetary Fund.

Following the convincing win by Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats in the German Bundestag elections in September, the feeling in markets had been that the Germans would be highly likely to continue with their bias toward a moderately hard-line stance on austerity and fiscal rectitude, which is deflationary and stifles growth at least in the short term.

Inflation and growth numbers out of Europe over the past several weeks have being pointing to a slowing in the anemic European recovery. There was even talk about a rising risk of deflation, which is almost universally agreed to be even more devastating to economies and company earnings than than inflation.

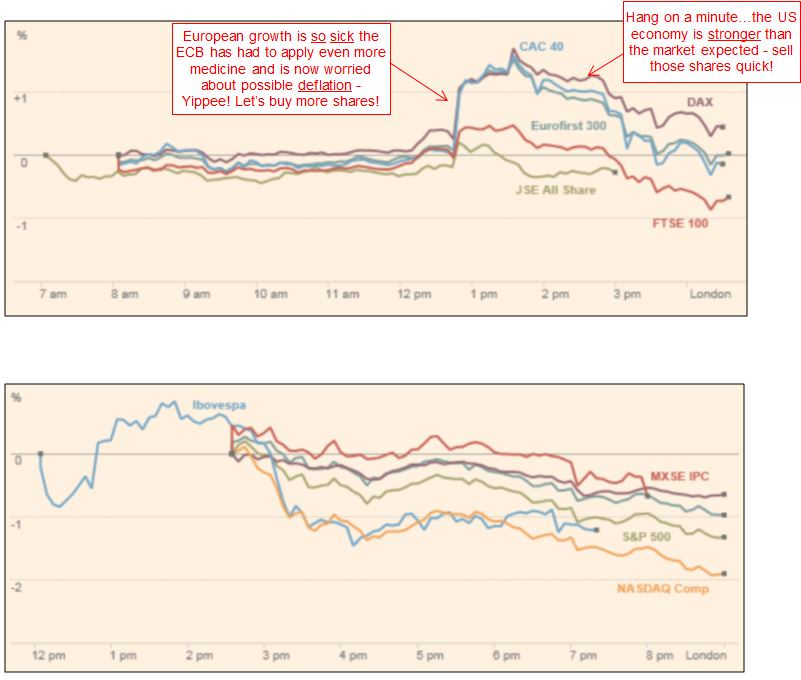

European markets were trading flat in the morning until the announcement of the ECB rate cut. The moment the ECB announced that European growth was so sick the ECB has had to apply even more medicine to the ailing patent on life support, and that possible deflation was on the cards, investors all across Europe rejoiced and raced in to buy more shares at higher prices!

US economic growth

Then the second big piece of unexpected news hit the airwaves. The third quarter US economic growth number was better than expected and so perhaps the US would emerge from intensive care sooner than the market had previously expected.

Better than expected recovery for the US economy is good news for the prospects for company earnings and dividends and so should be good news for share prices - in theory.

But in practice such news was seen as bad news and investors across Europe, and in the US when markets opened there, dumped shares on the bad news that the economy and company earnings prospects were now improving.

The first chart from The Financial Times shows European markets during 7 November 2013. The second chart shows American markets opening after the ECB announcement, selling off across the board on the 'good news' of a stronger US recovery. Not even the successful Twitter listing was enough to lift markets.

Addiction to cheap money

The missing link is cheap money. Share prices are moved by the weight of investors’ money and most investors have become addicted to rivers of cheap money for the past five years. They are motivated more by the prospect of more cheap debt flooding the world than by the reason for the need for the cheap debt in the first place.

The US and European economies have been on life support in intensive care since the start of QE1 following the Lehman bankruptcy in September 2008. The weak economic recoveries and the stock market recoveries that began in early March 2009, and property markets more recently, were made possible, and supported, by an unprecedented flood of cheap money artificially created on a global scale by the major central banks of the world.

Markets work in mysterious ways, and not much of it has to do with text book theory.

That’s just one day - what about longer periods?

The above story relates to how markets worked on a particular day. Similar perverse relationships operate on much longer timescales, including monthly, quarterly and even yearly. For a fuller explanation, see this article on economic growth and market cycles.

For example, in 2012 global economic growth was below average, and earnings and dividends were flat or falling, but global stock market returns were above average. This followed 2011 when global economic growth was above average and earnings and dividends rose, but stock market returns were poor and well below average.

Going back further, in 2009 world economic growth contracted in the deepest global recession since the 1930s depression, but shares had a great year in 2009 and the world stock market index was up by 29%!

It pays to focus on what drives markets in the real world and not follow simplistic text book theories.

Ashley Owen is Joint Chief Executive Officer of Philo Capital Advisers and a director and adviser to Third Link Growth Fund.