For retirees with a defined benefit income stream, understanding how they will be impacted under the incoming superannuation reforms is a potential minefield. This article explains some of these complexities.

What are defined benefit pensions?

Defined benefit pensions promise members a defined series of payments, typically for life. Former public servants are the most common recipients, although some companies also offered these types of schemes to their employees. SMSFs were also able to offer their members defined benefit pensions up until 2005, although there was no guarantee that these funds could meet the pension payments. The amount received by the pensioner may index each year benchmarked to a factor such as CPI and the pension may be reversionary to a spouse upon death of the primary pensioner.

The Commonwealth Superannuation Scheme (CSS) and the Public Sector Superannuation Scheme (PSS) are Australia’s two largest defined benefit pension schemes although they have been closed to new members for a number of years. At 30 June 2016, there were around 110,000 pension accounts being paid from CSS.

The benefits paid to pensioners from a public sector scheme are generally not tax free after age 60 like those paid from an account-based pension (ABP). This is because some or all of the benefit is paid from an untaxed source meaning it is paid directly by the Government and not from the member’s accumulated superannuation contributions and earnings. The untaxed component of a benefit is treated like a salary subject to tax at the pensioner’s marginal tax rate, however once a pensioner reaches age 60 they will receive a tax offset and be subject to tax at marginal tax rates less a 10% offset.

How are these lifetime pensions valued under the transfer balance cap?

From 1 July 2017 there will be a cap of $1.6 million on amounts that can be transferred into the tax free retirement phase. Defined benefit pensions must be included in the value of total retirement phase balances that count towards this cap.

For the purpose of valuing defined benefit income streams, the transfer balance cap legislation identifies specific types of annuities and pensions as ‘capped defined benefit income streams’.

Members may need to talk to their fund in order to determine whether their defined benefit pension meets this definition. Typically the definition will be met where it is a pension that is non-commutable, has no residual capital value, is paid for life, and the size of the benefit payment each year is fixed or indexed according to defined terms.

A capped defined benefit income stream that is payable for life will be assigned a ‘special value’ under the transfer balance cap equal to 16x annual entitlement. The annual entitlement is worked out by annualising the first income stream benefit payable in an income year.

For example, consider a pensioner who has a lifetime capped defined benefit income stream at 1 July 2017 which is paid monthly. Their first payment for the income year will be paid on 31 July for $10,000.

The annual entitlement for the purpose of the transfer balance cap is 12 x $10,000 = $120,000.

The special value of the income stream for the purposes of the transfer balance cap is 16 x $120,000 = $1,920,000.

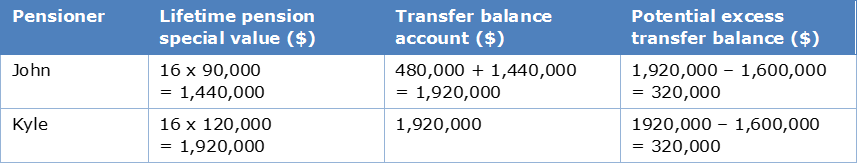

To see how this special value is used, consider two pensioners John and Kyle who are both over age 60 and receiving lifetime defined benefit pensions at 1 July 2017:

- John has a lifetime pension paying $90,000 per annum and also an ABP in a retail fund valued at $480,000 at 1 July 2017

- Kyle has a lifetime pension paying $120,000 per annum at 1 July 2017 and no other superannuation balances

At 1 July 2017, the following amounts will count towards John’s and Kyle’s transfer balance cap, potentially leading to an excess transfer balance:

Both pensioners have a potential excess of $320,000 above the $1.6 million transfer balance cap at 1 July 2017.

Dealing with excess transfer balances and lifetime pensions

John has an ABP valued at $480,000 at 1 July 2017 that is able to be commuted. The $320,000 excess must be commuted from the ABP balance to an accumulation phase superannuation account (or withdrawn from superannuation) to comply with the transfer balance cap.

John establishes an accumulation account with his retail super fund and commutes $320,000 from his ABP. At 1 July 2017 he now has:

- lifetime pension paying $90,000 per annum

- accumulation account valued at $320,000

John’s transfer balance account is equal to the special value of his lifetime pension plus the value of his ABP = 1,440,000 + 160,000 = 1,600,000. No transfer balance cap excess remains.

Kyle also has an excess of $320,000 however his lifetime pension is non-commutable. Special rules come into play which excuse the potential excess transfer balance. Rather than reducing the pension to comply with the cap, Kyle’s pension will be subject to different tax treatment.

Changes to tax treatment of defined benefit income

Where a pensioner has a capped defined benefit income stream they will be subject to the defined benefit income cap. This is set to the general transfer balance cap divided by 16. At 1 July 2017 this will be $100,000.

There are some complex rules to determine a retiree’s personal defined benefit income cap that depend on the tax treatment of income payments. Generally where a pensioner receives income solely from an untaxed source, or solely from a taxed source and the pensioner has attained age 60, at 1 July 2017 their defined benefit income cap for the 2017-18 year will be $100,000.

Income in excess of an individual’s defined benefit income cap will be treated differently depending on whether it was from a taxed or untaxed source. In essence, 50% of an excess amount from a concessionally taxed source will become assessable income for the individual and not eligible for any tax offset. An excess amount from an untaxed source will not be eligible for the 10% offset in the pensioner’s tax return, i.e. the tax offset will be capped at $10,000.

Pensions paid from public sector schemes often include an untaxed source amount and may or may not also contain a taxed source amount. Defined benefit income streams paid from an SMSF will not contain an untaxed source.

In 2017-18, Kyle expects to be paid $120,000 from his lifetime pension. His pension is paid from a public sector scheme and is solely from an untaxed source meaning his defined benefit income cap is $100,000. His excess untaxed amount is therefore $120,000 - $100,000 = $20,000

As Kyle is over age 60 he would normally apply a 10% tax offset to his entire $120,000 income in his tax return. In 2017-18 Kyle will only be eligible to apply the 10% tax offset to $100,000 of his assessable defined benefit income. The remaining $20,000 will be subject to his full marginal tax rates.

Conclusion

Pensioners should speak with their income stream provider to understand the type of defined benefit pension they hold and the tax treatment of income payments. This information can then be used to determine how the pension will be treated under the superannuation reforms.

Further detail on the treatment of defined benefit income streams including detail on how to treat scenarios not fully explored here can be found in Accurium’s decision charts for defined benefit income streams here.

Melanie Dunn is the SMSF Technical Services Manager at Accurium, a leading provider of actuarial certificates for SMSFs and a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This is general information only and is not intended to be financial product advice. It is based on Accurium’s understanding of the current superannuation and taxation laws and Accurium is not liable for any loss arising from reliance on or use of the information.