There are valid reasons why economics is called the dismal science, and even the origin of the expression is distasteful. The words were first used by historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle in a piece in 1849 called ‘Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question’ when he wrote that economics would justify a return of slavery to improve productivity of plantations. The term was later applied to the theory that population growth would outstrip resources and lead to global misery. An honours degree in economics often does not feel honourable.

In the current day, the dismal label should apply to the ability of economics and finance to draw contradictory conclusions from the same information. Good news is only good news until someone says it is bad.

Weaker economy: good or bad for share prices?

The good news is bad news makes it difficult to understand and predict markets. Throw in politics and it’s completely confusing, such as:

- If data shows a slowing economy or rising unemployment, the likelihood of interest rate reductions increases, and the stockmarket reacts favourably. So that’s weaker economy equals good for equities. Go figure.

- At the same time that the Reserve Bank is increasing rates to slow economic activity and reduce inflation, the Government announces ‘cost of living relief’ and encourages increasing wages. The economics demands job losses, the politics offers protection. How does that work?

Bad both ways, apparently

There are many other economic perversions. Some of the following examples are drawn from exchanges between Sam Ro and Michael Antonelli, US-based writers and analysts. They have collected examples of what they call bad both ways narratives which prove the market can say anything to justify a movement one way or the other, such as:

1. Retail sales

Falling consumer spending is bad because it signals a slowing economy and risk of a recession, while rising consumer spending is bad because it places upward momentum on prices and inflation, leading to higher interest rates.

When companies such as Coles and Woolworths report strong sales in private label goods, it’s a bad sign for the economy because it shows more people are cutting down on major brands. But when Coles and Woolworths report sales below expectations, it’s a bad sign because consumers are cutting back.

2. Lending activity

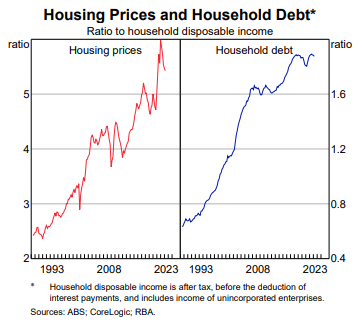

When individuals and businesses borrow more, especially in Australia with a high household debt to income ratios, it’s a bad sign because people are overleveraged and exposed to rising rates and economic downturn. When they borrow less, it’s a bad sign because it shows less confidence and a failure to take advantage of investment opportunities.

3. Market volatility

Heightened variation in stockmarket prices is bad because it shows uncertainty and a lack of confidence in the future, while low volatility is bad because investors have become complacent and unrealistic and will suffer setbacks when the market falls.

4. Interest rates

When long-term interest rates rise, it’s bad because other assets such as property and shares fall as their future cash flows are discounted at a higher rate. But long-term rates falling is bad, especially when there is an inverse yield curve, as it shows the market is pricing in a slowing economy.

5. Oil prices

Falling oil prices demonstrate weak demand which is bad for economic activity, while rising oil prices are bad because it heightens inflation fears and higher interest rates.

6. Home prices

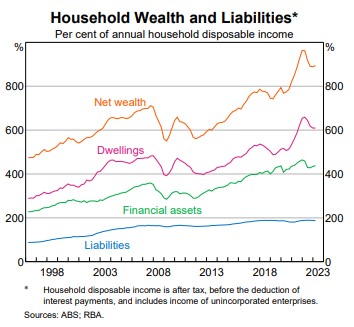

Rising home prices are a bad sign because aspiring homeowners are priced out of the market, while falling home prices are bad because owners feel a drop in their wealth and become less optimistic. Most of the net wealth of households is tied up in dwellings, far ahead of other financial assets.

7. Tech-driven market rally

A rally in the market such as driven by the ‘Magnificent Seven’ (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Tesla and Meta) is bad because traditional industrial companies (in Australia, the likes of Amcor, Orica, Brambles, Aurizon, CSL) who make and do real things cannot attract capital, and the techs mask overall market weakness. But it’s bad if these tech companies fall because they are all great companies with the strongest growth outlooks and they dominate the index.

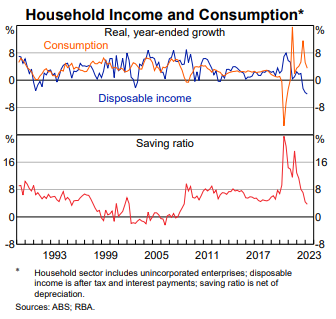

8. Individuals saving

A high savings ratio is bad because consumers are cautious and not spending, and during the pandemic, too much money was handed out leading to future deficits. But a declining savings ratio is bad because households no longer have the buffers to withstand higher interest rates or a slower economy.

The good and the bad of generative AI and indexing

Two more good is bad (or this time, is it bad is good?) themes in investing currently are the dramatic impact of generative AI (such as ChatGPT) and the rise and rise of index funds at the expense of active management.

Generative AI is more recent while the growth of index has been ongoing for years, but there is a similarity between the two. In both cases, the winners need the losers to continue to function.

Consider how the winners, generative AI and indexing, operate:

1. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) uses algorithms to create new content by searching existing content in its many forms, such text, images, audio and video. AI requires content providers, such as journalists, editors, film makers, sound engineers and photographers to produce work from which AI can ‘regenerate’ another version.

For example, if ChatGPT is asked ‘Write 100 words on active versus index investing’, it searches for existing content on the subject and produces an AI version as follows:

"Active and index investing represent two distinct approaches in the realm of investment strategies. Active investing involves portfolio managers or individual investors making deliberate decisions to buy and sell securities in an attempt to outperform the market. This method relies on extensive research, market analysis, and timing to achieve higher returns.

On the other hand, index investing follows a passive approach, aiming to replicate the performance of a specific market index. This strategy involves investing in a diversified portfolio that mirrors the index’s composition. It generally offers lower fees and reduced risk but might not generate the same potential for significant gains as active investing."

It’s a fair summary. The good news for journalists is that AI needs people to write the original content. Without journalists adding continuously to a body of knowledge, AI will itself become out of date. But the bad news is that AI will remove some of the jobs of the people it relies on. Why pay a journalist to write an article on active versus index when ChatGPT will produce it for free in a few seconds?

2. Index investing (as AI conveniently explains) holds stocks in the same weighting as the index it seeks to replicate. It does not attempt analysis of a company’s prospects. In contrast, active managers undertake fundamental research on the value of a company, and buy when their analysis suggest the market price is below the intrinsic value. Therefore, active managers are allocating capital based on estimated value, they undertake price discovery and therefore set the market price. In The Index Revolution, Charles Ellis says indexing relies on:

“trusting that active professionals have set securities prices as correctly as possible”

Ellis claims 95% of market trading is done by active investors. The 5% by indexers is more ‘set and forget’ with scheduled rebalancing around the index weights. There is an alternative view that so much money now flows into index funds that they set the valuations by pumping more money into popular stocks.

The bad news for active managers is that indexing needs fundamental analysis to set prices, but the bad news is that fewer active managers are needed as money flows into index.

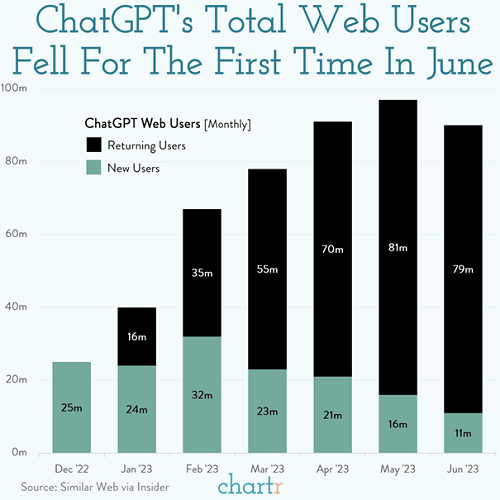

Some good news for content creators is that there are early signs that the initial fascination with ChatGPT and similar is waning, as returning and new users numbers have started to fall.

The dismal science explains everything … and nothing

Analysts, journalists and commentators are capable of drawing any conclusion following the release of economic statistics, and generative AI will use the content to produce an ‘on the one hand, on the other hand’ explanation. The market may react either way.

Next time a fund manager or analyst presents their earnest and thoroughly-researched conclusions, know there is an equally-qualified person making the totally opposite argument.

Graham Hand is Editor-At-Large for Firstlinks, and this article is general not personal information.