Hybrid securities issued by banks have become mainstays of many portfolios, especially those of retirees looking for income. The four major Australian banks plus Macquarie have issues worth almost $40 billion currently listed on the ASX. Hybrid structures have evolved over time but they are complex and idiosyncratic including characteristics of both equities and bonds. They have an ability to absorb losses like equities but pay a defined income like bonds. With income at a tempting 'yield' of 7%, it's important to understand what the number means.

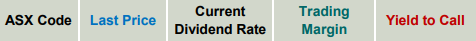

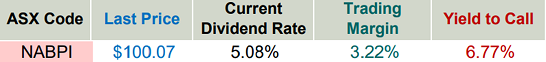

This article is not a primer on hybrids but focusses on why hybrid yields seem strangely high in the current market conditions. Here is an example of recent hybrid pricing on five prominent issues (updated from NAB on 24 August 2022).

The table shows 7% or more 'yield to call' from every major bank plus Macquarie Bank (ASX:MQGPF) at a healthy 7.47%.

The double-your-money magic

There is something magical about compounding, as demonstrated by the famous ‘Rule of 72’. Albert Einstein is quoted as describing compound interest as ‘the greatest mathematical discovery of all time’, although this is probably apocryphal. One of the richest bankers in history, Baron Rothschild, described it as the Eighth Wonder of the World. The founder of Vanguard, Jack Bogle, said, ‘Compound interest is a miracle.’

The Rule of 72 is a simplified mathematical construct which provides an approximation of how long it takes to double an investment. Dividing 72 by the rate of interest gives the number of years it takes to double the capital. It's sometimes called the ‘doubling time'. A return of 7% - and heroically assuming interest payments are also reinvested at 7% - doubles an investor’s money in about 10 years in nominal terms (no adjustment for inflation) and ignoring tax.

Why are hybrid yields reported so high?

At first glance, the reported 7%+ returns on hybrids look incorrect. Let’s consider a specific example of one of the more liquid hybrids, NAB Capital Notes 6 (ASX:NABPI), issued with a margin of 3.15% over the 90-day bank bill rate.

How can a hybrid security with a margin of 3.15% over the bank bill rate of 1.93% (at the time of writing) give a reported yield of around 7%? Shouldn’t it be 3.15%+1.93% equals 5.08%? Moreover, hybrids pay distributions adjusted for the corporate tax rate (requiring the investor to claim the value of the franking credit to gross up the return), so the actual distribution rate is only 3.56%.

Here is a typical calculation in a hybrid distribution report.

BBR: 1.93%

Margin: 3.15%

Total: 5.08%

Multiplied by (1 - tax rate): 0.7

Distribution rate: 3.56%

How do we reconcile the investor receiving 3.56% with the reported yield of around 7%, as in the hybrid pricing reports in our Education Centre?

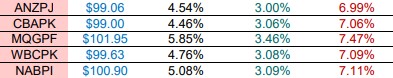

Let’s look more closely at NABPI. Although many retail investors might feel they missed out on a NABPI allocation due to the Design and Distribution Obligations (DDO) preventing access during the offer period, NABPI opened trading at around $98 (for a $100 note) giving easy entry to anybody. It has steadily traded up and is now around 101 giving a neat gain to anyone who bought early on-market.

Price of NAB Capital Notes 6 from issue to 22 August 2022

Source: CommSec

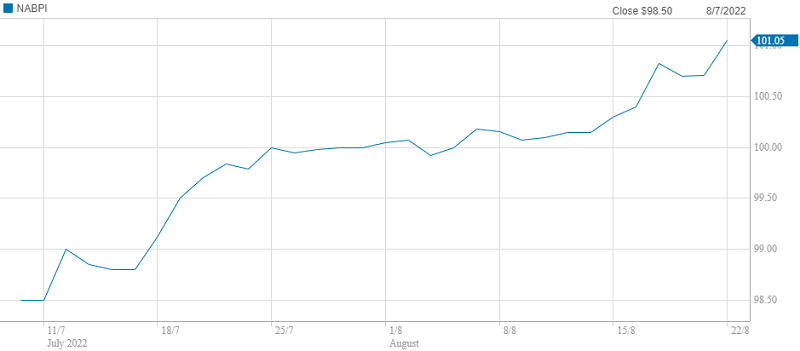

The following screenshot shows how NABPI is summarised in NAB's daily hybrid report. Most columns are self-explanatory, on issue size, issue date, first call date for the issuer, years remaining to call and issue margin.

At the date of the screenshot, the bank bill rate was 1.93% and with the margin of 3.15%, the ‘Current Dividend Rate’ was reported as 5.08% (1.93%+3.15%). The reason the price is above par but the Trading Margin is higher than the yield (which again seems intuitively wrong) is because the Last Price includes accrued interest. So far, so good.

But the question remains. How do we get to 6.77% yield as the headline return?

Reported hybrid yields are based on the future

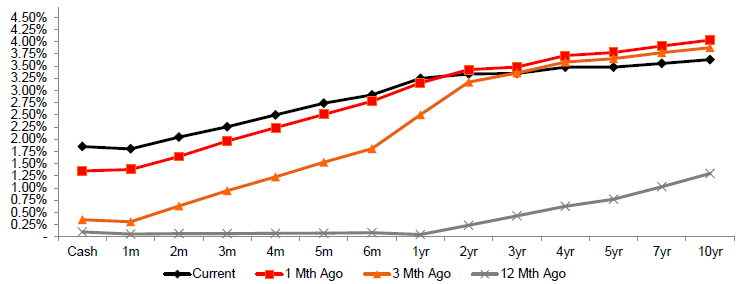

The 90-day BBSW rate is crucial for the distribution received by hybrid investors, and a rising BBSW leads to higher distributions. The reported margin in the table above allows for the market’s future projection of the 90-day BBSW rate over the life of the note, in the case of NABPI, over 7.4 years.

The 6.77% ‘Yield to Call’ (YTC) is based on the future distributions until the optional redemption date, not the current distribution. Although the option to repay in December 2029 is NAB’s choice, Australian banks are expected to pay on first call as an act of good faith to the market. Banks often rollover to a new issue at the time of first call, giving the market confidence about the term.

NAB (and the entire market) uses an interpolated swap rate, as shown in the chart below. Based on 7.4 years, the swap rate was 3.55%. The YTC figure is the Trading Margin (to call date) plus the swap rate (6.77%=3.22%+3.55%).

Bank Bill Swap Rates

Source: NAB as at 9 August 2022.

(At the date of final edit of this article on 24 August 2022, the YTC on NABPI was 7.11%, significantly higher than the 6.77% used in this example).

Is it worth investing in major bank hybrids at 7%?

For income-starved retirees, an investment in a major bank note paying 7% has plenty of appeal. It is not far off the long-term return expected on major bank shares, with considerably less price risk. If inflation is persistent and high, and the Reserve Bank goes harder on cash rates, the bank bill rate may rise higher than anticipated by the current swap curve, at least in the early years. But while the structure gives some protection against this rising inflation, there is always a risk that higher rates will lead to a recession and a need to lower rates, forcing returns below the 7% level.

This floating return is not like buying a fixed rate bond paying 7%. The distribution will rise and fall with short-term rates, and the 7% is only indicated until the 2029 call, not the full 10 years required for a doubling.

There’s no free lunch in investing, and hybrids come with greater risk than bank deposits. This article is not a full review of hybrid terms, but there is an enormous range of different features, most notably the ability to suspend payments in certain circumstances. Hybrids can also be converted to bank shares during periods of severe difficulty, placing capital at greater risk.

But it's worth understanding how the pricing is calculated and whether investors are paid adequately for the extra risk. The 7% rate depends on the shape of the current yield curve, but these hybrids may deliver a doubling of capital in a decade for the first time on a major Australian bank note for many years.

Graham Hand in Editor-At-Large for Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Disclosure, Graham's SMSF holds an investment in NABPI although this is not a recommendation, it is used for illustration purposes only.