Late October 2017 was the 30th anniversary of the 1987 crash and much has been written about it already. There are two key questions relevant for investors today:

- Are we in a bubble like 1987 that is about to burst? and

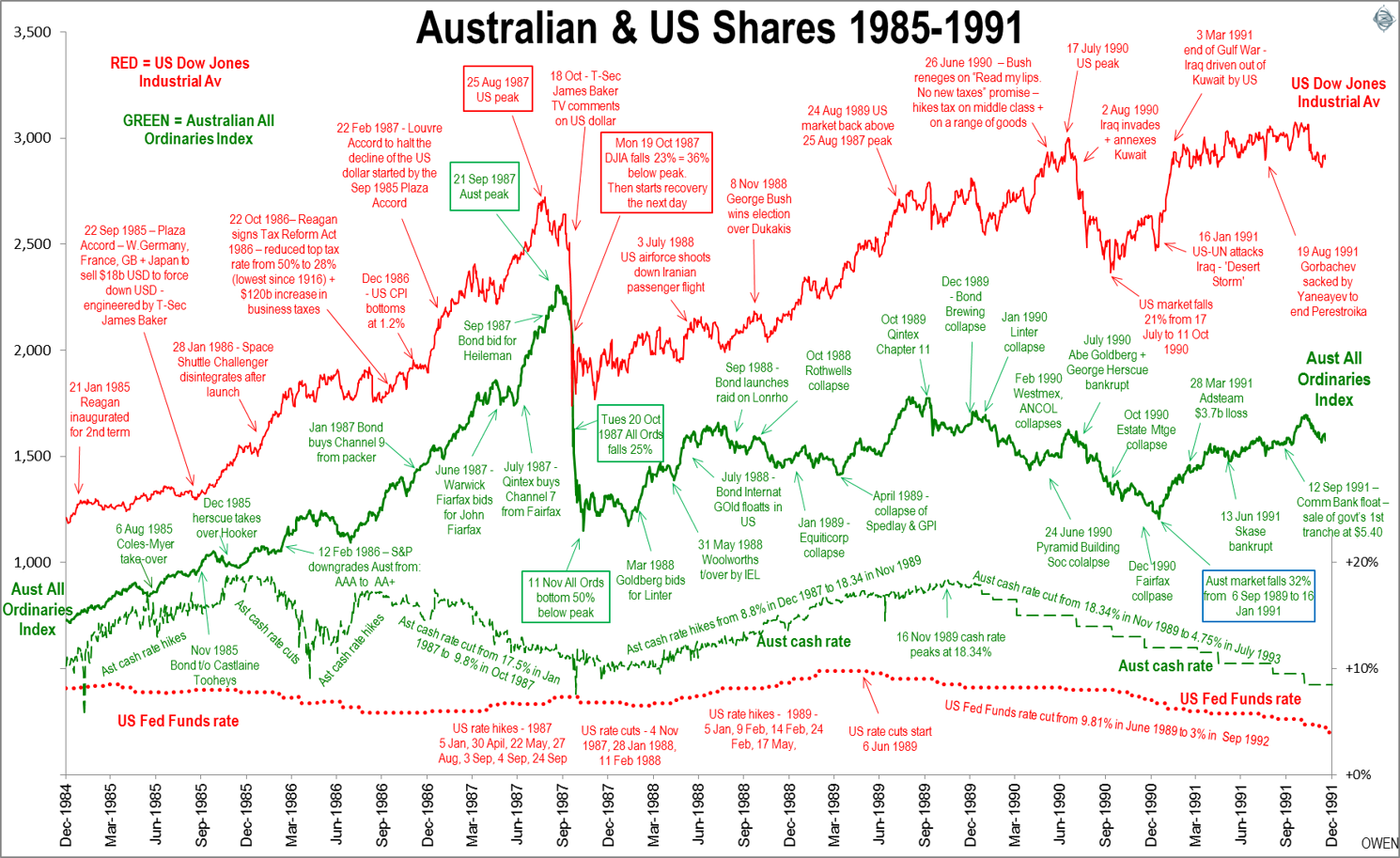

- Why did the Australian market crash further then and take longer to recover (10 years) than in the US (2 years)?

The two questions are related.

The debt-fuelled takeover binge

I have studied every cycle in the Australian and US stock markets since the 1800s and it is clear that the overall Australian market prior to the 1987 crash was the most expensive and vulnerable to crash that it has ever been in its history. There have been bigger bubbles and busts, but the 50% fall in 1987 in only 19 trading days (including a 25% fall on 20 October) was the steepest.

The main causes were loose lending, lax accounting and straight out fraud in many cases. The final trigger was the US/German/Japanese currency war, but the real problem was the extreme level of overpricing. This was worse in Australia than in the US or elsewhere. Most commentators cite the ‘price/earnings’ (PE) ratio of 21 as high. But a ‘price/earnings ratio’ is meaningless because the ‘earnings’ side of the equation was grossly inflated by fraudulent accounting, dodgy valuations and tame, conflicted auditors.

It was the age of the debt-fuelled corporate raiders with bankers throwing money at them. Alan Bond (Bond Corp, Media, Brewing), Robert Holmes à Court (Bell Group, Resources), Ron Brierley (IEL, Brierley Investments), John Spalvins (Adsteam), John Elliott (Elders IXL), Larry Adler (FAI), Russell Goward (Westmex), Chris Skase (Qintex), George Herscue (Hooker), Bruce Judge (Ariadne), Kevin Parry (Parry Corp), and many others. Most collapsed into bankruptcy in the 1990-91 recession, and some went to jail. Many of the big listed companies were caught up in the debt-fuelled takeover fever - even BHP, two of the big banks, the big retailers (Coles, Myer, Woolworths), the TV stations (Nine, Seven, Ten), Fairfax, the brewers, and several raiders themselves. It was all fuelled by ultra-loose lending from the big banks (with the notable exception of NAB) and from the state banks as well (the 1980s lending binge destroyed the State bank of every State except Qld which no longer had one).

At the top of the market the raiders were still cheap with low ‘price/earnings’ ratios: Elders was on 13, Bell Group on 15, IEL on 19, Bell Resources on 12, Adsteam on 11, Hooker on 15, Bond Corp and Ariane on just 9, and FAI on 7! Bargains! PE ratios were meaningless. The problem was in the quality of the reported ‘earnings’.

Are we in a 1987-style market bubble now? No.

Lessons from 1987 have stayed with me

The experience of 1987 affected me personally and it is at the core of my investment philosophy. 1987 serves as a reminder to ignore finance theory and focus on what happens in the real world. Finance theory likes nice neat lines, it assumes markets are always stable and static, that buyers and sellers are perfectly rational, and that returns are ‘random’ and ‘normally distributed’. It dismisses major events like the 1987 crash as random anomalies, simply ignoring them as irrelevant outliers and placing little importance on them.

I believe in the exact opposite - that the extreme outliers are actually the cornerstones of our experiences, they define our lives, and can create or destroy wealth - much more so than so-called ‘normal’ markets.

I was lucky enough to be on right side of both the 1987 boom and the crash. I had started out in the early 1980s as a lender with Citibank and Midland Bank (now HSBC). I learned about booms and busts first-hand by cleaning up the aftermath of bad lending in the late 1970s building boom which collapsed in the early 1980s recession. (Yes, you can lose money in housing - big time - just wait for a recession! Remember them?).

By 1986 I was running a bank financial control operation. Markets were booming again and I was young and single with no debt so I left the safety net of a salary, moved to Sydney, teamed up with three other characters and we set up a boutique investment bank. We were a motley bunch and I was the youngest, a bank financial controller with a couple of law degrees and a speciality in spreadsheets (remember Lotus 1-2-3, the forerunner of Excel?). This picture of me is from a 1987 prospectus.

My four fundamental rules

Rule 1: Recognise when you are in a bubble or a bust. Easy enough from a distance but it’s harder when you are actually in it at the time.

Rule 2: Never buy in a bubble - sell instead. Likewise: never panic sell in a bust - buy instead.

Rule 3: If you’re in a bubble and have nothing to sell, build something and sell it, assuming you have the skills and background to do it quickly. In 1986-87, we built and listed four companies - two gold refineries, a finance company, and a ‘cash box’ (a cash box is the ultimate bubble stock - there's nothing in it except cash but in a bubble people bid up the price anyway).

Rule 4: Never use debt (very unfashionable in the debt-fuelled 1980s. Debt was like big shoulder pads and skinny ties - everyone had them!)

In 1986-87, there were signs of a bubble everywhere - ‘hot stock’ shows on TV, talk back radio, magazines, newspapers (there were no blogs or social media or internet back then and not even mobile phones). There was even a tax-driven reason to lure investors into the market as franking credits were introduced in July 1987. Stock brokers ran seminars in the suburbs convincing people to gear up and buy shares to get access to the hot new toy called franking credits! The same thing happened in the 2007 boom when hundreds of seminars in the suburbs encouraged people to gear up into superannuation to take advantage of the ‘$1 million contribution window’. Thousands of people borrowed money at the top of both of the booms, threw it into the market, and promptly lost most it in the crashes that followed immediately after.

Don’t lose control of your own destiny

The other half of Rule 2 is that in a bust, buy when everybody else is panic selling. If you have no debt (Rule 4) you can survive even the worst crash and retain control. It is sad to see people sold up by margin lenders in busts. When you borrow money, you give control to the lender, and they will sell you up at the worst time.

The All Ordinaries index collapsed by 50% from 2,306 on 21 September 1987 to 1,151 on 11 November 1987 but that masks the fact that hundreds of stocks were left completely without buyers. The true market had probably collapsed 70% or more if there were any buyers to set market prices. We picked over the ashes and bought one of the Elders group companies for $1 (not $1 per share, $1 for the lot, with no debt). It had 35 subsidiaries and we spent the next couple of years sorting through the ruins

1987 was a great learning experience for me. I do have regrets. There were a few things we developed that went nowhere, but if you have no debt the downside is limited. Also, I was probably too careful and should have taken more risk at the time. You can always make more money if you borrow - but I’m too cautious and not that greedy.

The lessons and the same four rules have applied in every cycle since. And because all markets are driven by human fear and greed, hard-wired into human nature, the same four rules will probably apply to all cycles in future as well.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.