It’s fair to say geopolitics is the most fraught it’s been in the last two decades.

The battle over energy between Russia and Europe has been dominating headlines, while more recently, Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan has set the US and China on a pathway of competitive escalation.

Semiconductors and tech independence play a critical role in US-China relations, and this cannot be resolved quickly given both countries are dependent on Taiwan – or specifically Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – for the manufacture of leading-edge chips.

For some time now the US has prevented a small number of Chinese firms from accessing US-designed semiconductors and the equipment to make these chips where it was assumed this technology was being used for military purposes. As tensions between the two global superpowers soured further, we noted the tail risk was how far the US would push to more broadly limit China’s ability to innovate.

The US has indeed now taken a further step – introducing sweeping new controls that can limit exports to China of critical technology used to manufacture semiconductors.

Here’s what the US Department of Commerce said in an announcement regarding the move:

“The Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) is implementing a series of targeted updates to its export controls as part of BIS’s ongoing efforts to protect U.S. national security and foreign policy interests. These updates will restrict the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s) ability to both purchase and manufacture certain high-end chips.”

The details of the new controls show the US is targeting GPU, CPU and DRAM (memory) chips designed in the last five years and the equipment to make these chips, as well as NAND (memory) chips designed over the last three years. There are also specific rules limiting China’s ability to import certain AI chips widely used in datacentres and critical to many modern consumer applications.

While this policy stops short of a blanket ban, the goal is to restrict China’s access to chips and other technology related to advanced AI and super-computing as these have military applications.

What are the consequences of this move?

Most leading-edge semiconductor chips essential for high performance computing are designed by US or European companies such as Nvidia, AMD, Broadcom, Marvell, Intel. But the chips are not necessarily manufactured by these companies.

In fact, at the leading-edge these semiconductor chips are almost entirely manufactured by TSMC.

TSMC has actively retained its leading-edge chip capacity at home in Taiwan, a strategy referred to as the ‘silicon shield’. But what’s interesting here is that more than half of the equipment used to manufacture globally critical chips comes from the US, with the rest from Europe and Japan.

If Europe and Japan choose to follow the US’ lead, it places China in an extremely challenging position. Inability to access chips and furthermore the equipment used to manufacture these chips will meaningfully hamstring not only China’s ability to keep up with tech developments in the West, but also hinder China’s capacity to develop tech independence.

At first blush, the development of Chinese hyperscalers such as Tencent, Alibaba and Baidu could be impacted as the bulk of datacentre spend is AI-centric even for current consumer use around content creation, search and natural language programming.

Chinese EVs may also see progress curbed relative to Western peers as ADAS chips (advanced driver assistance systems) could be affected. At this stage restrictions on handset chips appears unlikely given the limited crossover with military applications. The language framing these restrictions, which are some of the most comprehensive we’ve seen to date, suggests these restrictions could be part of a rolling series.

Much remains up in the air

How rigorously will the US enforce these license approvals? Will Europe and Japan follow suit? How might the US expand export restrictions or worse initiate bans? Will China retaliate, and on a longer-term basis can China develop this technology internally?

China could choose to respond in a targeted fashion directed at high profile US brands with large profit pools in China such as Apple, Tesla, Nike and Estee Lauder amongst others. China could limit US access to strategic markets that it dominates such as rare earths in the EV battery supply chain.

If the US were to escalate further via an embargo on all investment in China, it would be an extremely negative outcome, not just for China but for the global economy and asset markets.

At this stage we still consider a Taiwan ‘hot war’ scenario relatively remote given the US and China’s co-dependence on Taiwan, or should we say TSMC. For now, China and the US are critically aligned in maintaining a stable Taiwan for the sake of their respective economic stability.

Uncovering winners in an evolving geopolitical landscape and new market regime

With regards to the escalating tensions between the US and China, we think it is critical investors monitor developments closely and consider global vulnerabilities should China choose to retaliate.

When it comes to the broader global macroeconomic environment, stagflation (high inflation combined with lower economic growth) remains our base case, and with a mild recession, as China has the potential to loosen monetary policy even as the West is tightening.

The US economy, however, bears close watching as the risk of a ‘hard landing’ is rising. If the Fed over-tightens to control inflation it risks dragging the US into a deeper recession.

The year so far has been challenging for global equities. Economic data is rapidly weakening, consensus estimates on our analysis are broadly still too high and equity inflows have been slow to reverse. Despite this, opportunities exist. The likely winners in today’s world look very different to the winners of yesteryear.

The QE-led growth/long duration regime that dominated the post-2008 investing period is transitioning to a regime that will see policy makers lean on fiscal stimulus to prop up economic activity. In the near term this stimulus will focus on the cost-of-living crisis (as already seen in the UK and Europe), but over the longer term it will focus on investment around decarbonisation, infrastructure and security (defence and supply chains).

The US’ Inflation Reduction Act is a great example of this trend. It supports $370 billion worth of investment in energy security and climate change with almost one-quarter of the programme dedicated to re-shoring solar, wind and battery production in the US.

In global markets, there are great opportunities for investors to position for these trends.

While the range of outcomes around inflation and global economic activity remain high, our view is that defensive exposures and beneficiaries of longer-term investment trends can outperform.

Examples of these exposures in Antipodes’ portfolios include:

- Merck (NYSE:MRK): lower drug pricing risk and manageable patent risk relative to peers, and a diversified earnings stream from long duration businesses including vaccines and animal health.

- Gilead (NASDAQ:GILD): HIV patent cliff pushed out while new treatments are developed to extend dominance, and an under-appreciated pipeline.

- SAP (NYSE:SAP) and Oracle (NYSE:ORCL): dominate the ERP/enterprise resource planning market (general ledger and accounting software) where transitioning this mission-critical software to the cloud has become a priority in our post-COVID hybrid work environment, and this transition is continuing in even a tougher economic environment.

- Diageo (LON:DGE): leading spirits business with 5% share of total alcohol consumption globally that is taking market share in categories that are growing and is facing lower inflationary pressures than other defensive parts of the market such as consumer staples.

Thinking outside the unipolar lens

Finally, when looking at geographic diversification, global investors may be well served by considering the world through a multipolar lens.

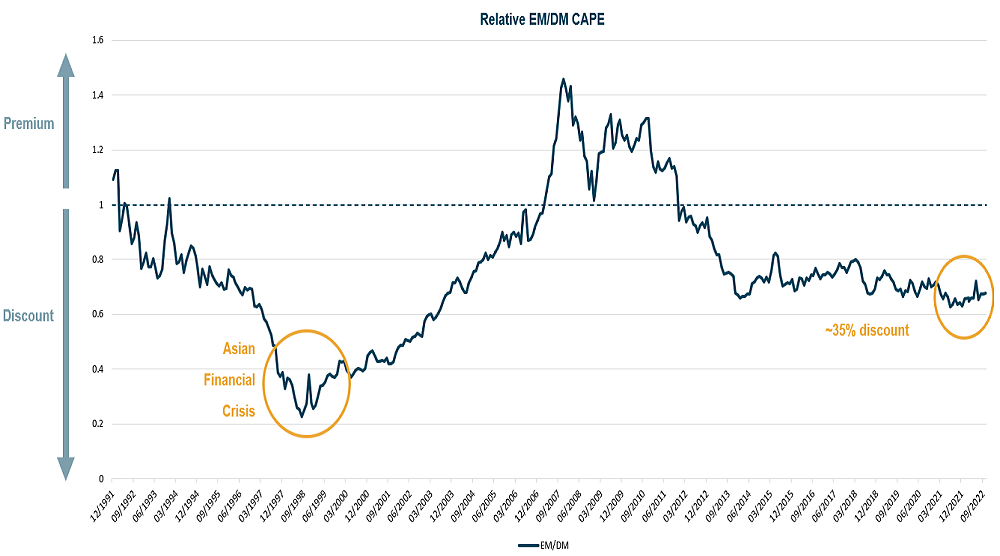

Emerging markets are valued at around a 35% discount to developed markets – one of the largest discounts in the last 20 years. But while EM hasn’t been a popular asset class in recent times, we have been increasing increase exposure to emerging countries such as Indonesia, Mexico and Brazil which are beneficiaries of the evolving multipolar geopolitical landscape, and where valuations and growth rates are attractive.

Source: Antipodes, Factset

Indonesia, for example, is benefiting from structural reform following almost a decade of political stability. It has a large and young population, and hurdles around labour laws and infrastructure are being removed. It is a beneficiary of higher commodity prices and can also benefit from diversifying manufacturing bases that are heavily centred in China.

Likewise, Mexico can be a beneficiary of on-shoring and near-shoring manufacturing, which has become a major initiative for US corporations.

In Brazil, the recent passing of the election reduces political risk and balancing the cabinet with more centrist candidates could see President Lula achieve an attractive balance between spending and reform.

Further, currency and bond markets in these countries are showing a high degree of resilience due to much tighter long-term fiscal and monetary policy settings versus many Western equivalents.

So, while we are witnessing one of the most complex environments investors have had to navigate in decades, it’s an environment that has also presented pragmatic global investors with great opportunities.

Alison Savas is a Client Portfolio Manager at Antipodes Partners. Antipodes is affiliated with Pinnacle Investment Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

For more articles and papers from Pinnacle and its affiliates, click here.