One of Scott Morrison’s first decisions as Prime Minister was to abolish the plans to increase the eligibility requirements for the age pension (pension) to age 70, announced originally as part of the unpopular 2014 budget. At the time, then Treasurer Joe Hockey (Abbott Government) planned to lift the pension age from 67 to 70. The move back to 67 is good public policy. It reduces the pressure on vulnerable people who, through no fault of their own, do not have the physical capacity to continue to work up to the age of 70.

The working age problem and increases in life expectancy

A quarter of the total population in all advanced economies is expected to be aged over 65 by 2050. Australia is no different, with the number of people aged 65 to 84 expected to double, and the number of people aged 85 and older expected to quadruple, over the same period. At present, the cost of the pension is approximately 2.6% of Australia’s annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP), or $44 billion. It is predicted to remain relatively stable and is comparatively affordable when compared to an average of 3.9% of GDP among advanced economies.

To provide context, the age pension commenced in 1909 when eligibility was set at 65 for males and 60 for females. At the time, life expectancy at birth was 55.2 years for males and 58.8 years for females. Today, life expectancy for males is 80.4 years and for females 84.6 years.

To negate some of these impacts, Australian Governments (the former Labor and current Coalition) have attempted to gradually extend the working age. At present, the former Labor Government’s policy changes include the steady rise in eligibility age from 65 through to 67 by 2023. The Coalition’s scuppered plan was a gradual rise to 70 by 2035.

The question for future policy makers

If a future Government increases the pension age, will retirees look for alternative forms of Government assistance to maintain their expected income at the retirement date they had anticipated?

To extrapolate and make reasonable inferences about the future, it is important to consider the past. There could be a relationship between increasing the age requirements of the pension and people accessing the Disability Support Pension (DSP).

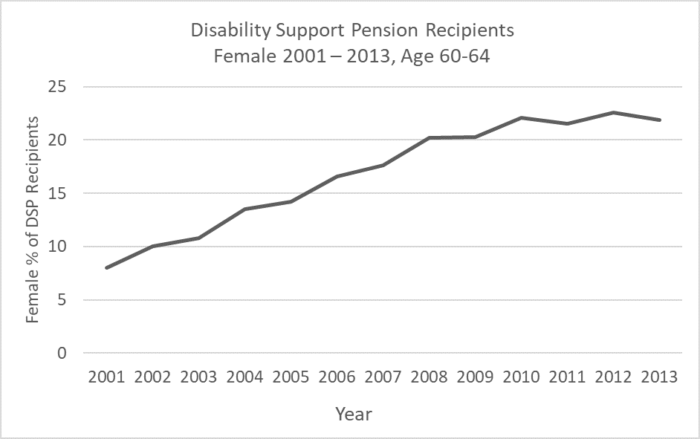

From 1995 until 2013, the pension qualifying age for women gradually increased from 60 to 65 years, while the requirement for men remained fixed at 65 years. Over this 18-year period, the overall percentage increase in women accessing the DSP increased 174%, compared to a 36% increase for men.

The monetary value of the Government assistance for the pension and DSP (including supplements) is identical for both genders, at $908 per fortnight for singles. It could be reasonably inferred that if the pension eligibility requirements are increased, some Australians may seek to apply for the DSP to maintain their expected retirement income and retire at the date they had originally anticipated.

Between 2001 to 2013, the percentage of female DSP recipients aged between 60 and 64 increased from 8% to 21.9%. This is a substantial increase and requires more analysis to accurately determine all the factors underpinning this outcome.

Nevertheless, in 2012, the then Labor Government overhauled the DSP eligibility requirements due to the exponential growth in DSP recipients. This policy change resulted in a comprehensive assessment of all new DSP applications, including a determination as to whether the applicant could undertake any form of work, as opposed to relying on a medical diagnosis. The Coalition Government has since made it even more difficult to qualify, with an individual now required to prove that their permanent disability prevents them from working more than 15 hours per week.

Source: Department of Social Service

Protection of vulnerable people

Australians who rely solely on the pension in retirement are among the most vulnerable members of our society. They are subject to regular variation of asset and income testing requirements from Governments of all persuasions.

Unfortunately, these Australians have not been able to accumulate substantial superannuation savings through the compulsory superannuation system. As the system was made mandatory in 1992, part way through their working lives and through an initial contribution rate of only 3%, many have not become financially independent in retirement. It is unfair to expect these Australians to work for longer periods of time, often in physically-demanding roles that their bodies are no longer strong enough to carry out.

Two-thirds of females who receive the DSP do not own a home, and 72% of females receiving the DSP are single, separated, divorced or widowed. Australia has a responsibility to support its vulnerable. The abandonment of the plan to increase pension age to 70 is not only good politics, but good public policy.

Adam Shultz is Executive Manager of Policy at Mine Super and a Councillor for Lake Macquarie City Council. He holds a Master of Public Policy from the University of Sydney. This article represents the personal views of the author and not those of his employer.

For more articles and papers from Mine Super, please click here.