Who is the greatest ever investor? Most of you will inevitably answer: Warren Buffett. Yet, what if I told you that there’s another contender, one who has an even better track record over an extended period?

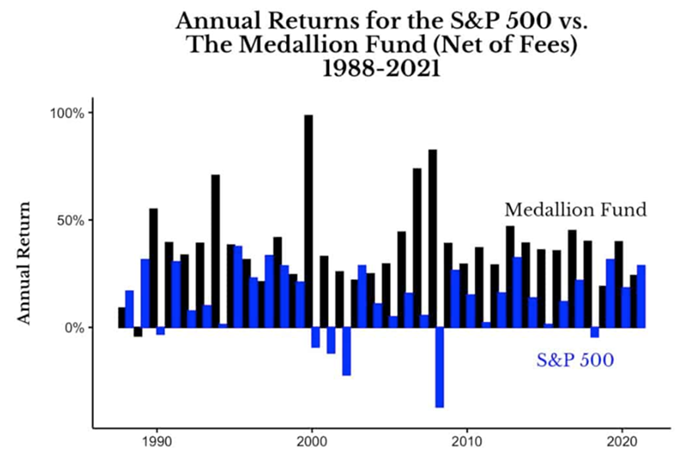

Hedge fund investor Jim Simons’ flagship Medallion Fund has returned an astonishing 62% per annum over 33 years. $1,000 invested in his fund in 1988 would have grown to more than $8 billion by 2021.

Image by Gleuschk - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Net of substantial fees (he’s charged a 5% annual fee plus 44% performance fee, compared to the standard 2% and 20% respectively for the normal hedge fund), Simons has still generated 37% annualized returns over 33 years.

To put that in context, $1000 invested in the fund would have grown to almost $42 million, net of fees, from 1988-2021, while $1000 invested in the S&P 500 would have turned into $40,000 over the same period, and the same amount invested with Warren Buffett would have grown to $152,000.

Source: DFA, Gregory Zuckerman

Simons has only lost money in one year out of those 33 years. He’s also made money when almost everybody else is losing it. For instance, in 2008, the Medallion Fund made 82% net of fees compared to a loss of 37% for the S&P 500.

So, how has Simons done it?

The maths prodigy

Let’s first explore the man behind the track record. Simons is a maths prodigy who completed his PhD in mathematics at Berkeley at the slender age of 23. He went on to become a prize-winning academic who contributed to the development of string theory, which merged quantum mechanics with Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity.

During his time as an academic, he also worked with the National Security Agency (NSA) to help break codes during the Cold War.

From 1968-1978, he led the maths department at Stony Brook University in New York, which he turned into a world-class academic powerhouse through the recruitment of some of the world’s leading mathematicians.

By 1978, Simons thought his pattern recognition skills could be applied to the world of investing.

Renaissance Technologies

He partnered with a former colleague Leonard Baum to form an initial fund, but it didn’t go accordingly to plan. They made a lot of money until the market crash of 1984 where their investments lost 40% of their value. The partnership dissolved soon after, and Simons is quoted as saying that Leonard had mastered the "buy low" technique but hadn't perfected the "sell high" part.

Simons set about refining his techniques. He sifted through huge amounts of data from primary documentary sources, as well as electronic data. He then hired world-class mathematicians and data scientists. He got his employees to study correlations and patterns that could be traded in large volumes and numerous securities.

Yet, the initial years weren’t easy. In its first year, the Medallion Fund returned 9% net of fees versus the S&P 500 which was up 16%. It’s second year was much worse, as the fund returned -4% net of fees compared to the S&P 500’s gain of 30%.

One of the initial partners then left the firm and Simons brought in a game theorist named Elwyn Berlekamp, who revamped Renaissance’s trading systems. The changes worked and the following year, the fund returned 55%, and in subsequent years, it obliterated the indices.

The fund’s secret sauce

Simons was a pioneer in quantitative investing. That is, finding patterns and asymmetries in data to make small profits, and magnify those profits through leverage.

As Gregory Zuckerman notes in his biography of Simons:

“Early on, Simons made a decision to dig through mountains of data, employ advanced mathematics, and develop cutting-edge computer models. While others were still relying on intuition, instinct, and old fashioned research for their predictions. Simons inspired a revolution that has since swept the investing world.”

Simons tries to keep human emotions and judgments out of his investing.

“Simons and his colleagues hadn’t spent too much time wondering why their growing collection of algorithms predicted prices so presciently. They were scientists and mathematicians, not analysts or economists. If certain signals produced results that were statistically significant, that was enough to include them in the trading model”.

And he sides with his computer models even if they don’t make complete sense:

“More than half of the trading signals Simons’ team was discovering were non-intuitive, or those they couldn’t fully understand. Most quant firms ignore signals if they can’t develop a reasonable hypothesis to explain them, but Simons and his colleagues never liked spending too much time searching for the causes of market phenomena. If their signals met various measures of statistical strength, they were comfortable wagering on them.”

However, Simons isn’t a robot and there have been instances where he’s overridden his models. On at last one occasion, he’s traded counter to his models with panicked selling of investments. In 2018, he also temporarily lost faith in his trading systems.

His detractors

You don’t become rich and famous without having detractors, and Simons is no different. Notably, Charlie Munger in one of his final interviews said he was uncomfortable with investors who principally used algorithms like Renaissance Technologies. He said these funds essentially front run investors. And Munger believed that they were making smaller profits with more volume, and the only way that they were still making good returns was through using greater and greater leverage, “which I would not run myself”.

Meanwhile, notable investment author, William Bernstein, questions the purpose of hedge funds like Renaissance:

“Clearly, the quant hedge fund business has little to do with the primary societal purpose of capital markets – the efficient allocation of capital to productive enterprises. Rather, it is a zero-sum game that transfers wealth from those endowed with skill and luck to those less well endowed with them…

… Were quantitative hedge fund managers to suddenly disappear, would they be missed? Or might the world be a better place without them?”

Lessons from Simons

Quantitative trading may be foreign to most investors, yet there are still lessons to learn from the likes of Simons, including:

1. You’re not Jim Simons. The greatest investors including Simons, Buffett, and Soros are maths geniuses. You can’t hope to emulate them. Accept that, and instead formulate an investment strategy that best suits you.

2. Don’t compete with the best and brightest. Quant trading is for experts. If you’re trying to make day trades based on technical analysis and other techniques, you need to be aware that you’re most likely competing with computers and the world’s brightest maths minds.

3. Find your edge. You need to find your edge in markets. It could mean being a long-term investor, a deep value one, focusing on a certain sector that you are familiar with, or other approaches. Whatever it is, it needs to fit with your strengths and goals.

4. Wherever possible, remove emotions from investing. Investing is a hyper-rational endeavour, yet every investor is prone to emotions and biases. Even Jim Simons is. The trick is to find ways to minimize the instances of emotions override rational thinking.

Some fund managers go to radical lengths to achieve this. For example, Guy Spier in his book ‘Education of a Value Investor’ says he deliberately removed having Bloomberg screens in his office so he couldn’t constantly check stock prices. He even ended up moving away from the ‘noise’ of Wall Street to a quiet village outside Zurich to ply his trade:

“Following my move to Zurich, I focused energy on this task of creating the ideal environment in which to invest – one in which I’d be able to act slightly more rationally. The goal isn’t to be smarter. It’s to construct an environment in which my brain is not subjected to quite such an extreme barrage of distraction and disturbing forces that can exacerbate my irrationality.”

5. Find a smart partner. Perhaps Simons greatest achievement has been creating a world-class team. He recognized early that he needed to hire the best minds to make his fund work.

You probably don’t have the luxury of hiring others, though it doesn’t stop you from finding other like-minded and smart investors to bounce ideas off. Investing doesn’t have to be a solo sport and collaboration can make for better returns.

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au