(Sections of this article are republished and updated from a piece first published in 2018).

The Financial Services Royal Commission has done an excellent job uncovering poor behaviour, including conduct that is already contrary to the law. It has exposed negligent practices, particularly in financial advice and insurance. Some parts of banking, such as the use of mortgage brokers and loans to small businesses, have been examined in detail.

It was evident during the final weeks of the Commission, as bank CEOs took the stand for the first time, that Kenneth Hayne was struggling with how to define culture. The Australian Financial Review counted 471 mentions of 'culture' in the final 10 days of hearings. It might be the most important question but one that will attract little attention, as there are doubts to what he can do in a practical sense. Hayne has already said the laws are adequate, even if regulators have not enforced them.

So is culture the 'the way we do things', the vision, the unwritten rules or personal accountability? Hayne settles on this recommendation in his Final Report:

"Changing culture and governance

All financial services entities should, as often as reasonably possible, take proper steps to: assess the entity’s culture and its governance; identify any problems with that culture and governance; deal with those problems; and determine whether the changes it has made have been effective."

In his Executive Summary in last year's Interim Report, Commissioner Kenneth Hayne was refreshingly honest that simply passing new laws was unlikely to change much:

“The law already requires entities to ‘do all things necessary to ensure’ that the services they are licensed to provide are provided ‘efficiently, honestly and fairly’. Much more often than not, the conduct now condemned was contrary to law. Passing some new law to say, again, ‘Do not do that’, would add an extra layer of legal complexity to an already complex regulatory regime. What would that gain?”

This issue of ‘culture’ and problems defining it and changing may be the biggest hurdles to achieving long-term, sustainable change. Hayne said in the Interim Report:

“Changing culture in the Australian banks may not be easy and may take time. It cannot be assumed that entities will embrace change willingly or immediately. It cannot be assumed that entities will make desirable changes at all levels of the organisation.”

And there’s the critical issue. This is not about the bank CEOs offering apologies and accepting responsibility. It is about the thousands of day-to-day decisions made across the banks which affect millions of Australians which the CEOs never know about. In particular, the most significant impact on loans, deposits and services is what happens in the bank pricing committees.

We’ve gone down the culture path many times before

The former Chairman of ASIC, Greg Medcraft, did attempt to raise the culture issue and often found critics. For example, at the 2016 ASIC Annual Forum, the overall theme was ‘Culture Shock’, and Medcraft said:

“Inevitably, it is the stories of poor culture and poor conduct in the financial industry which are splashed across the front page of the newspaper, which pop up in our newsfeeds, and which are the subjects of heated discussion on social media sites.”

In response, former CBA Managing Director, Chair of the Financial System Inquiry and current Chair of AMP, David Murray, shot ASIC a cannonball when he told a Fairfax Media event on 5 April 2016 that it was:

“… extraordinarily disappointing that ASIC should go down this culture tangent which will do more damage than good … It’s anticompetitive, it’s inefficient, and to be perfectly candid, there have been people in the world who have tried to enforce culture. Adolf Hitler comes to mind.”

He later apologised for the Hitler reference, but this illustrates attitudes at senior levels of banking, and it was only a few years ago that Murray’s Inquiry was lauded for its work.

The then Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, weighed in with these strong words at a Westpac function on 6 April 2016:

“We expect our banks to have high standards, we expect them always rigorously to put their customers’ interests first, to deal with their depositors and their borrowers, those they advise and those with whom they transact, in precisely the same way they would have them deal with themselves. This is not idealism, this is what we expect … Wise bankers understand that banks need to very publicly demonstrate that their values of trust, integrity, placing the customers first in every way, they must be lived and not just spoken about.”

So we’ve done the culture and behaviour rounds many times before.

… including 300 pages in 2001

I chronicled my experiences in the way banks price their products in a book published by Allen & Unwin in 2001 called Naked Among Cannibals: What Really Happens Inside Australian Banks. As recently as 13 March 2016, Noel Whittaker quoted the book in the Courier-Mail:

“Despite the predictable protests from the banks [about rate-fixing and life insurance], there is nothing new in this. In 2001, ex-bank executive Graham Hand published his bestseller Naked Among Cannibals, which contained more than 300 pages about corporate greed and unethical behaviour by Australian banks.”

Anyone wanting to take a journey into bank culture 18 years ago can read the contents page and first three chapters for free on Amazon books here or purchase the 320 page eBook version here.

Banks have no equivalent of best interests duties

The Corporation Act 2001, Section 601FC(1), under ‘Duties of a responsible entity’ says:

“In exercising its powers and carrying out its duties, the responsible entity of a registered scheme must … (c) act in the best interests of the members and, if there is a conflict between the members’ interests and its own interests, give priority to the members’ interests.”

These duties apply to superannuation trustees, and therefore much of the wealth management industry, but not banks. There is no legal fiduciary duty in banking, and so culture and ethics must play a greater role in determining appropriate actions. Culture is the combination of beliefs, values and attitudes that guide behaviour.

What are examples of bank culture problems?

In 2003, I presented a Perspectives segment on ABC’s Radio National. The text is linked here. It was called ‘A Banker’s Dictionary’. I explained five terms – entanglement, milking, mating calls, lagging and parasites – we used in our Pricing Committee. It’s unlikely in these days of political correctness that all the terms are still used.

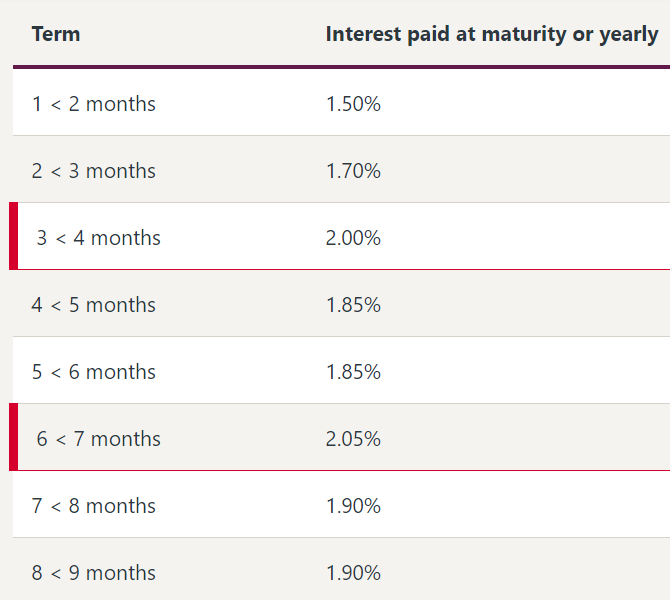

Do the activities these words describe still exist? Consider the current Westpac term deposit interest rate schedule, as shown below for 28 September 2018.

The rates highlighted in red are the ‘special’ offers. Why is the 3<4 month rate 2.00% when the 2<3 month rate is only 1.70%? It does not reflect the shape of the yield curve. Westpac has no particular need for 3<4 month money. It is the rate designed to attract new clients, and if you happen to be an existing client with a rollover for four months, you miss out on the higher rate.

It’s an excellent way to extract more profit margin from customers over time. Banks can vary where they offer the highest rates based on where the existing rollovers occur. For example, if a previous special offer means a large volume of maturities occur at a particular time, a lower rate will be set for this maturity. Like all banks, Westpac relies on what we called ‘retail inertia’. The majority of investors don’t ring the bank for a higher rate, they simply allow the deposit to rollover for the same term.

Is it fair that the 85-year-old who is living on term deposit savings does not realise better rates are readily available from her own bank? Few people want 1.85% for 4 months when 2.0% is available for 3 months. Why should a loyal, existing customer earn less than a new client or one that makes a call or shops around? It’s even been called a ‘disloyalty premium’. The same thing happens with loans at special rates only for new borrowers. The Commissioner should give Rowena Orr the chance to ask a bank CEO why customers must ring up to receive a market rate. It’s highly profitable in interest cost savings with billions of dollars of term deposits rolled over each year.

For the record, if CBA does not hold rollover instructions for a client, it places maturing term deposits into a Term Deposit Holding Facility (earning a rate of 1% for amounts between $10,000 and $99,999) until instructions are received from the client. You can judge whether this is a fair policy.

Banks also know that the more a customer is ‘entangled’ in an account, the less likely they are to leave. The best examples are at-call (cash) transaction accounts which link to direct debits to pay electricity bills, loan repayments, credit card balances etc., and direct credits receiving interest, salaries, dividends, etc. These accounts are so entangled that most clients cannot face the paperwork of changing to another bank or product. So why would the bank bother paying a decent interest rate on the balance? Most money in at-call or cheque accounts receives negligible interest despite all banks or their subsidiaries having more attractive deposit products. Shall we tell the client to switch to the online account that pays 3%? Are you mad?

There are many examples like these: slowly lagging cash rate reductions into lending rates but passing on increases quickly, or charging interest rates on credit cards of over 20% (which have so many embedded direct credits and debits that it’s hard for people to leave). And the mysterious calculations of early repayment fees on fixed rate loans, as previously described here.

Will the Royal Commission be a cultural turning point for banks?

Every major bank CEO has responded to the Royal Commission along the lines of this from Westpac’s Brian Hartzer:

“The Royal Commission has identified many examples of misconduct across the industry. I apologise to any customers who have been impacted by mistakes that we have made.”

Again, there is nothing new in these statements. At the 2015 AGM of the Commonwealth Bank, Chairman David Turner said on the bank’s ethics:

“We see it down the road as being an ultimate competitive advantage. We think we will be the ethical bank, the bank others look up to for honesty, transparency, decency, good management, openness. That is exactly where we are trying to go.”

And two-and-a-half years ago, the Chairman of National Australia Bank, Ken Henry, said in a speech on the future of banking on 5 April 2016:

“In a successful business the customer drives product design and the suite of products offered. No customer is encouraged to buy something they don’t need or charged more than they need to be charged to cover the cost of providing the product. No customer of a successful business buys something that they don’t understand well enough to have a high degree of confidence that the product will deliver what they want, when they want it.”

That’s a high bar to jump. How does it fit with NAB transaction accounts paying interest of 0.01% and NAB credit cards with interest rates of 21.74%? I went to university with Ken, and he’s a good bloke. But I do wonder if he has closely studied his bank’s pricing policies.

Where will changes in ethical culture come from?

The Royal Commission offers no silver bullets on how to change culture, and the CEOs and Chairs of the banks need to find a way to embed a better balance between all stakeholders, not only the 'profit before people' that Kenneth Hayne describes.

Change seems to come only when forced on the banks, as Carl Rhodes, Professor of Organizational Studies at UTS, summarised:

“This is not an ethical responsibility the banks have taken on voluntarily through their ‘ethical cultures’. Responsibility was thrust upon them as a result of the actions of citizens, employees, regulators, and journalists. If it wasn’t for them, the scandals would remain covered up.”

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Cuffelinks and he sat on the pricing committees of three banks from 1979 to 2001. Sections of this report are republished and updated from an article first published in 2018.