To make sense of today’s market conundrum, remember that things could have been worse than they are, and that investors are more defensive than they appear.

There was a question implied at the start of our last Asset Allocation Committee Outlook: How could we have called the overall challenging economic outlook, but then watched markets move in unexpected directions?

We are still asking that question deep into the second quarter, with another big bank failure under our belts and rising interest rates, yet equity markets are bouncing around seven-month highs.

What are we missing, in the economy or the structure of the market, that might explain these apparent disconnects?

Squeeze

Each time we run through all the reasons to be bearish on equities, we are struck by just how long the list is.

Monetary and credit conditions are tightening simultaneously, as both central banks and commercial banks rein themselves in. Yield curves remain steeply inverted, with high volatility at the front end.

Inflation is proving sticky everywhere, especially in Europe and the U.K., where the Bank of England faces a growing dilemma, and increasingly in Japan. Monetary policymakers who were tentative a few weeks ago, as the banking sector wobbled, have grown hawkish again. The market-implied probability of more rate hikes is rising again. Bank rescues and the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) decision to maintain its yield-curve control provided unexpected liquidity flows earlier in the year, but the effects are beginning to fade and reverse.

At the corporate level, realized and forecast earnings are declining and inflation is beginning to squeeze margins.

Add it all up, and closely watched aggregate indicators put the probability of a U.S. recession at around 70 – 80%. And that’s without an equally long list of exogenous tail risks: trouble within commercial real estate and regional banks, disruptive global flows when the BoJ begins its expected policy normalization, and an escalation of U.S.-Russia and/or U.S.-China tensions.

Nonetheless, equity markets keep nudging higher.

Starting over

One way to make some sense of this is to remember the starting point, as well as the direction things appear to be headed.

Yes, central banks and commercial banks are withdrawing liquidity, but there was a vast amount of liquidity to begin with, and there is still plenty out there. While the consumer may be softening slightly in the face of inflation, employment is high, wages continue to rise and there is still cash in pockets—and, among the more affluent, in savings accounts. Companies are generally not over-leveraged or facing imminent refinancing pressures. And the fiscal impulse remains positive, even as the monetary impulse has turned negative.

Another thing to remember is that, while some things seem bad, they could have been even worse.

Yes, inflation is proving sticky. But imagine, for a moment, that you’d been offered all the good news associated with the reopening of China and the resilience of jobs markets at the start of the year. Might you have turned that good news down over worries that it would stoke commodity prices and inflation more than it has?

Looking at it this way reminds us that interest rates could have been far higher today than they are, and companies and consumers could have been much more sensitive to them than they have been. Where there is sensitivity—bank balance sheets, for example—central banks have shown themselves ready and willing to intervene and take out the tail risk. Perhaps investors are recognizing that the cycle may be less volatile than they feared nine months ago.

Signals

Another way to square things up is to question the signals we are taking from the markets.

It may appear that investors are strangely calm in the face of flashing red recession alarms and swirling tail risks, but appearances can be deceiving.

A month ago, I noted the contrast between low volatility in equity markets and exceptionally high volatility in fixed income. Two weeks later, Joe Amato wrote a “Tale of Two Indices,” noting how a handful of mega-cap tech stocks were making the S&P 500’s performance and valuation look much better and higher than the underlying reality. Nvidia, having more than doubled in price already this year, was up almost 25% in a single day last week, after smashing analysts’ earnings expectations.

It is an observable fact that underlying factor and sector volatility is actually very high but masked by the dominance of that handful of mega-cap tech stocks. There is a good deal more market uncertainty about the path of the economy than the index return suggests.

Why has this small group of mega-cap tech stocks broken free of the underlying uncertainty? Given the sudden flurry of excitement around advances in artificial intelligence, investors may be seeking out potential beneficiaries of this kind of transformative technological change.

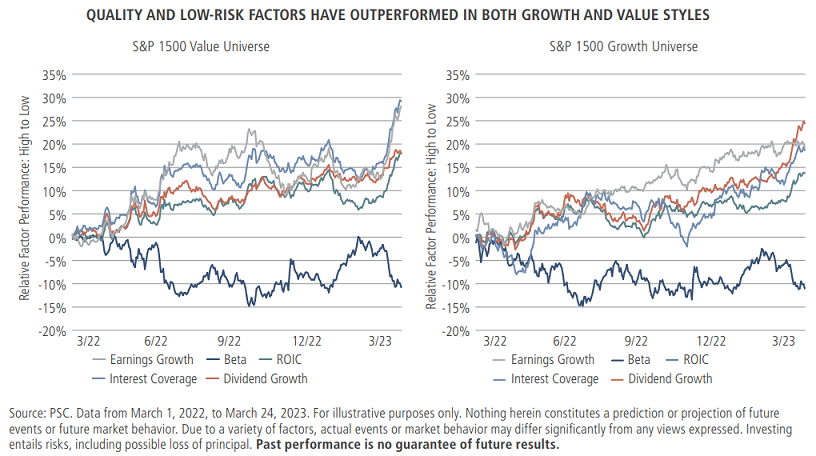

But it is also possible that they have started to trade like safe-haven assets at a time when traditional havens such as U.S. Treasuries and the dollar are beset by doubt. As noted by my colleague, Raheel Siddiqui, it is not the growth or value style factors that have outperformed so far this year, but quality, low-beta and low-risk factors across every style.

Perhaps market participants are more concerned than they look, after all.

A mix of dynamics

To resolve the puzzle, recognize that the reality is likely a mix of these dynamics. The global economy could easily have been in a much worse state than it is, given the conditions it faced toward the end of last year. And investor positioning is more defensive than it appears.

With that in mind, while we may need to look again at how we think about quality and safe havens, the main pillars of our outlook remain intact. Now is not an opportune time to seek out broad equity market risk, in our view—and the market seems to agree. We don’t think long-duration assets are the place to be over the coming cycles: The more resilient the economy is to higher rates, the more likely they are to stay high. And with short-dated rates as high as they are, the opportunity cost of waiting out the uncertainty is low—even if the frustration of waiting is occasionally high.

Erik L. Knutzen, CFA, CAIA and Managing Director, is Co-Head of the Neuberger Berman Quantitative and Multi-Asset investment team and Multi-Asset Chief Investment Officer. Neuberger Berman is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This information discusses general market activity, industry, or sector trends, or other broad-based economic, market or political conditions and should not be construed as research or investment advice. It is not intended to be an offer or the solicitation of an offer.

For more articles and papers from Neuberger Berman, click here.