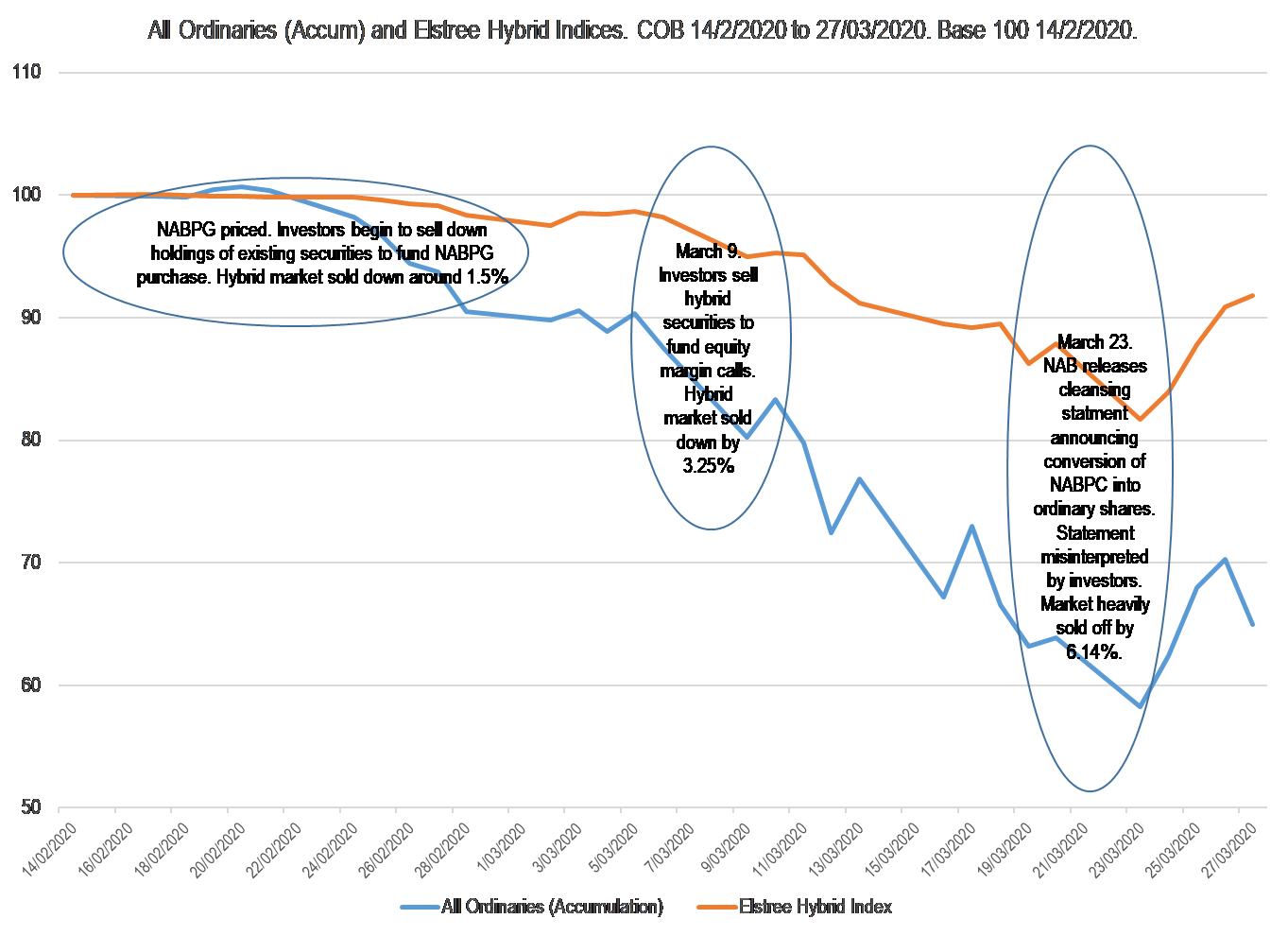

Professionals working in capital markets like to think we are comfortable with the market's ups and downs, but the reality is we never really get used to the severe ‘downs’. From 2 March 2020 to the close of business on 23 March, the Elstree Hybrid Index declined by a massive 15.7%. Six trading days later on 31 March, the index had managed to claw its way back such that it was down, over the month, by a relatively pedestrian 6.2%.

Let's make sense of this behaviour.

We thought the GFC was the template

No matter how much information we have at hand (perfectly informed - is there such a thing?) and how much modelling and back testing we conduct when things go awry, markets do not necessarily react in a way that we predicted or hoped they would.

The coronavirus-induced equity market collapse is a classic case in point. The GFC, while a bad event, provided asset managers with a source of behavioural data we could only dream of. There hadn’t been an ‘event’ like it in decades, some would argue in fact, since the 1930s.

As market analysts, we learned a lot from the GFC. In the lead up to it, the banks self-regulated and because there hadn’t been any serious default activity among borrowers, particularly households, the banks apportioned significantly less capital to loans they wrote than perhaps they should have. Credit ratings agencies were lulled into a false sense of security with their modelling that displayed almost zero default probability among different cohorts of loans pooled together in so-called ‘structured products’.

We thought we had been blessed because the raft of default activity and the magnitude of the event that followed provided us with a template from which we could make a meaningful assessment of how markets would likely behave when the next ‘event’ occurred.

We understand that no two events are the same. In 2008 we were confronted by a credit event that spread like a virus through the banking system, almost crippling it. It was only the combined actions of the central banks and the governments of the day that saved the banking system from almost certain failure.

In 2020 we are confronted by a virus of a different kind, a virus that is impacting economic growth not through a lack of credit creation but from the top down as communities and countries are isolated and locked down. The impact on economic growth is similar only the way we got here is different.

Are we paid enough for the risk?

As investors in hybrid capital instruments, we spend much of our time determining whether or not the compensation we receive over the risk-free rate compensates us sufficiently for the sum of the risks. Hybrid securities are subject to a plethora of risks including default risk, equity conversion risk, extension risk, liquidity risk and fat tail (black swan) event risk. These risks are captured and present as ‘market risk’.

For some time now, we have been sanguine about default, forced equity conversion and extension risk of the majority issuers of hybrid securities, the banks. Despite the expected economic hit of Covid-19 and the potential impact of non-performing loans on lender balance sheets, our view hasn’t changed. In support of our view that the banks are well positioned from both the capital and funding perspectives, the Reserve Bank moved on 19 March to secure a large percentage of all Australian ADI funding by providing a $90 billion 3-year fixed rate facility. Then APRA announced that the banks could effectively ‘gear’ their balance sheets by relaxing their unquestionably strong capital adequacy ratios.

While we understand that investors must have confidence that the issuer will meet all their scheduled payment obligations, changes in the market price of hybrids do occur from time to time that have nothing to do with the credit worthiness of the issuer. It is a result of the behaviour of panicked investors.

We question that it really was increased default, forced equity conversion and extension risk that caused the most rapid and sharpest decline in hybrid security prices since the GFC especially in the face of the RBA and APRA’s initiatives. We believe the drawdown which ensued, while having some other plausible explanation, was mainly caused by a lack of liquidity.

Liquidity risk is perhaps the biggest risk investors in ASX-listed hybrids face. We have just experienced a month like no other where an event shock led to severe market dislocation, panicking investors into selling large volumes of securities only for the market to recover strongly as the month drew to a close.

Selling pressure forced rapid increase in turnover

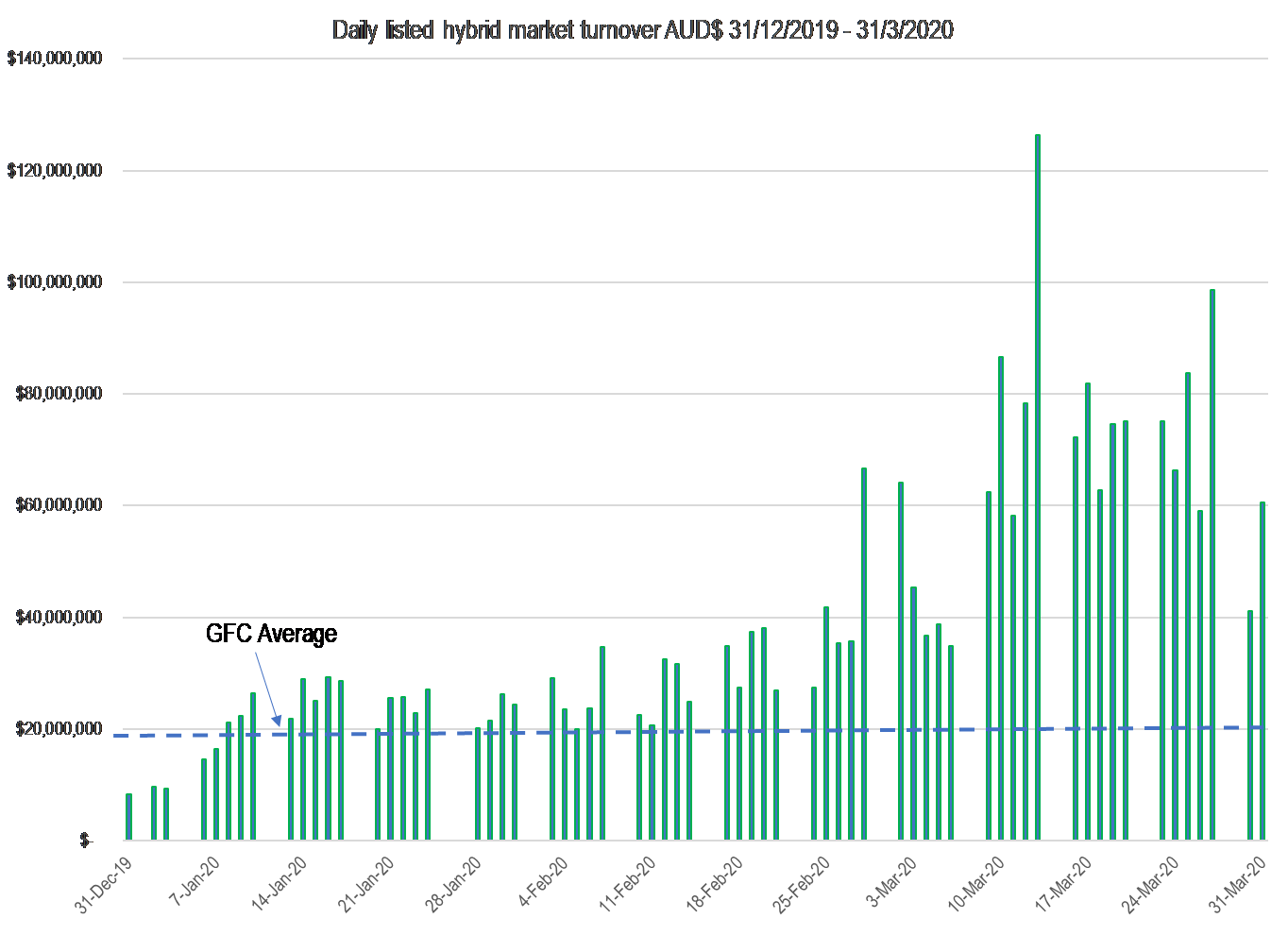

The listed hybrid market transacts on average during normal periods around $30 million a day or $150 million a week. Turnover of this magnitude is sufficient to ensure price stability where the supply of securities is met by demand. Where transacted volume exceeds $150 million a week price pressures begin to emerge. Transacted volume typically increases during periods of stress (such as now) or when a new issue is announced and priced.

In the fortnight prior to 25 March transacted volume exceeded $300 a week, or twice the long-term weekly average. On one day (13 March) it exceeded $126 million, or four times the average daily turnover. The chart below details the transacted volume on a daily basis since 31 December 2019 to the close of business on 31 March. The GFC average is highlighted (blue dotted line).

It’s a given that some downwards hybrid security price pressure should be expected as a consequence of Covid-19. However, it was the addition of a number of ‘other’ one-off factors that triggered the dramatic transacted volume surge as supply swamped demand forcing prices materially lower. These factors included:

- The selling down of securities to fund the purchase of the ‘upsized’ NABPG when investors became aware of their entitlements on or around 25 February 25 (NAB sensibly withdrew the issue on 12 March however investors were well advanced in the selling of their existing securities).

- There was margin lending-based ‘forced’ selling of hybrid securities (to fund margin calls on equities) coinciding with the equity market falls which gathered momentum around the week beginning 9 March. Hybrids and equities both fell in price.

- On 23 March, NAB confirmed the conversion of capital notes (NABPC) into ordinary equity. A number of investors erroneously interpreted the NAB’s communication (which included a general comment about how Covid- 19 might impact NAB’s business) to mean that the NAB would convert their redemption proceeds (being $100 plus the last coupon payment) into ordinary shares at price of $21.34 representing a 30% premium to NAB’s last traded share price. This spooked investors into selling everything ‘NAB’ and the market at large (including the equity market). The price behaviour that ensued was the direct result of investors not understanding the documentation or perhaps not even reading the relevant documentation. The issue of shares is commonplace where maturing hybrid securities are purchased and converted into equity by a 3rd party provider appointed by the issuer (usually an investment bank, in this case UBS). It has nothing whatsoever to do with investors receiving less than 100 cents. On 23 March, the hybrid market declined 6.1%. On the same day the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index declined by 6.0%

Expectation of performing better than during the GFC

With the GFC providing much of the data and the subsequent improved structure of hybrids, our modelling suggested that the market would perform significantly better should there be an event shock of similar magnitude. We expected any drawdown would be less, especially since the market is now represented by 95% investment grade issuers compared with 65% during the GFC period.

Typically, the hybrid market displays an equity market delta of around 0.1 (that is, if the equity market falls by 10% the hybrid market decline in value by 1%). Should the equity market fall by 20% or more than 20% the delta increases to around 0.2 – 0.3. However, the delta in the middle of March 2020 approached 0.4% which we thought was too high (of course, on 24 March the equity delta exceeded 1).

The listed Australian hybrid market is majority populated by unsophisticated and (sometimes) poorly-informed investors. The recent surge in transacted volume was panicked in nature. In two trading days two weeks apart, the listed hybrid market declined by a staggering 10%. This serves to highlight the inefficiencies and nuances that are inherent in listed hybrid market and investors are better served leaving the management of their hybrid securities exposure to a professional fund manager.

Norman Derham is Executive Director of Elstree Investment Management, a boutique fixed income fund manager. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual investor.