Over the past two years investors have faced a barrage of glowing research from the investment banks trumpeting the blue sky potential of new companies seeking to be floated on the ASX. What is also clear is that the overall quality of these new initial public offerings (IPOs) has been declining and investors should be more critical of the bright forecasts contained in the prospectuses.

Earlier this week we received the IPO offer documents for a company exposed to the buoyant domestic housing sector, valued based on the assumption that the current demand for new homes and apartments remains unchanged. Indeed one of their competitors that listed just over six months ago has already fallen 20%.

When analysing IPOs, few have been more eloquent on this subject than Benjamin Graham, the Father of Value Investing

“Our recommendation is that all investors should be wary of new issues – which usually mean, simply, that these should be subjected to careful examination and unusually severe tests before they are purchased. There are two reasons for this double caveat. The first is that new issues have special salesmanship behind them, which calls therefore for a special degree of sales resistance. The second is that most new issues are sold under ‘favorable market conditions’ – which means favorable for the sellers and consequently less favorable for the buyer.” (The Intelligent Investor 1949 edition, p.80)

The cycle

Typically during an IPO cycle, the higher quality businesses are listed first, generally at attractive multiples to overcome investor skepticism. When these floats perform well (and generate handsome fees for the investment banks), the more marginal businesses get listed. Then finally, towards the end of the cycle, investors will see companies that have been hastily cobbled together to take advantage of investor greed. Generally this window closes either due to a large negative macroeconomic event such as the GFC which reduces investors’ appetite for risk, or a particularly poor large float that burns investors’ fingers such as Myer in 2009.

Why is the vendor selling?

The motivation behind the IPO is one of the first things to look at. Historically investors tend to do well where the IPO is a spin-off from a large company exiting a line of business such as Orica and their paints division Dulux or the vendors are using the proceeds to expand their business. The probability of new investors doing well from an IPO is far lower when the seller is just looking to maximise their exit price and end their involvement with the company, a classic example of this was the Myer IPO. In situations like this the seller can be incentivised to make short term decisions to inflate current earnings such as economising on maintenance capex, if they are not long-term owners of the business.

Is the company profitable?

Any IPO is presented to the market in the most favourable light (albeit with a large number of disclaimers) and at a time of the seller’s choosing. Over the last six months we have seen a number of businesses being listed that have been unprofitable for a number of years, yet are expected to switch into profitability in the years immediately after the IPO. We put little store in the notion that companies are being listed for the altruistic benefit of new investors. Thus we are doubtful of such dramatic improvements after listing, especially when the IPO vendors have significant incentives to show profits before listing.

Can the business be readily understood?

Given the reduced level of historical financial data it is important that an investor can easily understand how the company makes money and its competitive advantage. We are wary of companies with complicated business models, as investors usually only have a few weeks (9 or less) to analyse whether to buy an IPO, whereas the seller has generally owned the company for five years or more. When Medibank Private was listed in November 2014, it was clear how the company made money from collecting insurance premiums from the public to settle hospital bills.

How attractive is the price?

The sole reason behind any new investment is the view that it will generate a higher rate of return than the alternative options in your portfolio. Additionally as the audited financial history may be limited or the financial accounts complicated by bolt-on acquisitions made in the lead up to the IPO, investors should build in an additional margin of safety and price the new issue at a discount to existing listed companies in similar industries. The Mantra Group hotel IPO in June 2014 was priced at an attractive PE of 12.7 times forward earnings, a 30% discount to the original price sought by the vendors in a failed attempt to list the business in March 2014. This allowed new investors an attractive entry point with a margin of safety. Conversely the May 2015 IPO of MYOB was priced at almost 24 times and at this level we saw minimal scope for price appreciation for new shareholders.

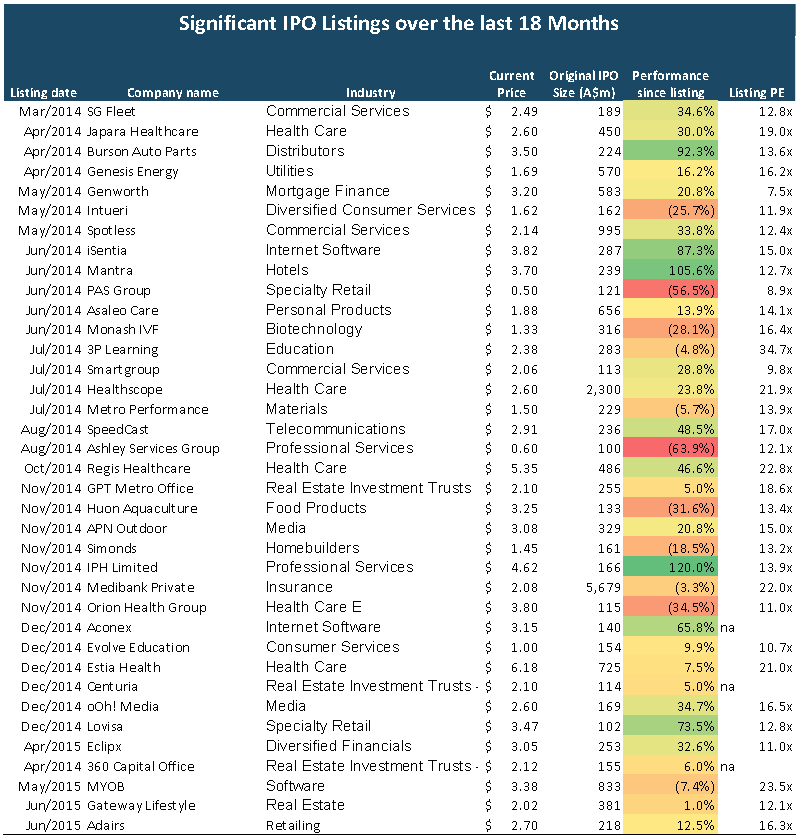

Source: Aurora Funds Management, IRESS & UBS

Recent action and consequences

In aggregate the market has invested $19 billion in new IPOs over the past 18 months and the weighted average return has been +13%, though with a large degree of variability in returns. Looking at the above table the most common industries for IPO listings are healthcare, real estate and IT and a successful float in one industry stimulates the investment bankers to bring similar-looking companies to market. A key factor in the companies that have done poorly has been structural issues with the business model or overly optimistic predictions of future profits as we saw in the recent downgrade of real estate trust Industria’s (floated December 2013) expected distributions.

Like all investment managers, Aurora is currently receiving around two to three 80-100 page pre-IPO research pieces a week, couriered to our desks by the sponsoring investment banks with a range of arguments why we should invest our clients’ capital in these new IPOs. Whilst new issues are presented as fresh, exciting ways for investors to make money, what we are looking for are situations where the vendor is deliberately under-pricing the asset being sold. As you can imagine, this is a very rare occurrence for profit-maximising private equity owners, who often seem to have little interest in the ongoing health of the business after their exit has been achieved.

Hugh Dive is a Senior Portfolio Manager at boutique investment manager Aurora Funds Management Limited, a fully owned subsidiary of ASX listed, Keybridge Capital (ASX Code: KBC). This article is for general education purposes and does not address the specific circumstances of any individual investor.