This article extracts sections from the author’s 2022 keynote address to the Jobs and Skills Summit, entitled 'Think big: a new mission statement for Australia'.

The address by Danielle Wood, CEO of the Grattan Institute, was widely praised. For example, speaking on ABC TV's Insiders programme, journalist Karen Middleton said:

"I thought Danielle Wood from the Grattan Institute, the speech she gave at the beginning, was excellent. It's the sort of speech you want to go back and read the text over again because it was a really good encapsulation of the problems we face and some possible solutions. I thought it was really excellent."

For detailed footnotes, to view the slides, or to read the full address, click here. Woods started her address by saying:

"I’m delighted to be invited to give this address and to set the scene for what I hope will be two days of robust conversation and forward policy momentum.

It is right that we open with a focus on full employment and productivity – somewhat abstract economic concepts yes – but ultimately ones that have a real impact on quality of life for each and every Australian."

---

We need to understand the lay of the economic land and how it is changing.

Too often conversations about economic policy happen in the rear-view mirror. They seek to preserve in aspic previous economic, social, and geographic structures.

This is often an expensive exercise in futility. We cannot push economic water uphill, but what we can do is make sure that we move with the flow and strive to provide good opportunities and jobs for Australians regardless of their location, sector, or personal characteristics.

And while I do not claim to have a crystal ball, I want to touch on three themes of change that will be important determinants of the shape of our economy and jobs in the decades to come.

Theme 1: The march of the services sector

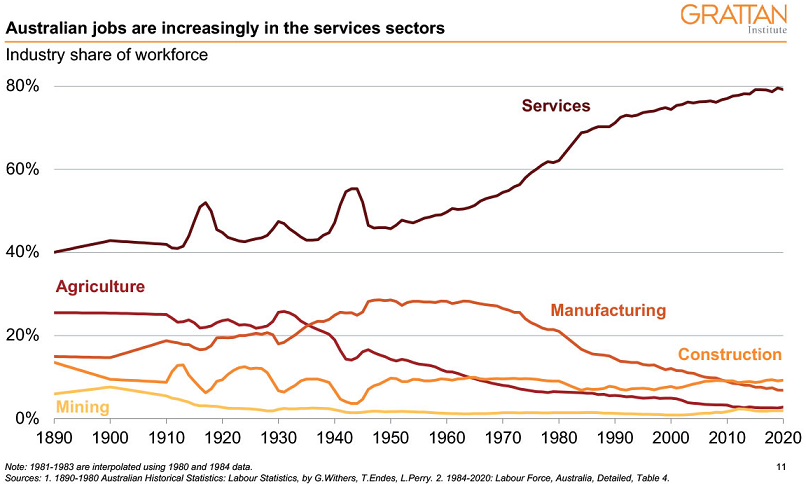

Over the past 100 years the Australian economy has undergone major sectoral transformation: essentially from an economy that made goods – ‘stuff you can drop on your foot’ – to an economy of services.

At the time of Federation, 1 in 4 Australians was employed in agriculture. By 2020 it was just 1 in 36. Manufacturing began its long decline as an employer in the 1970s. But in both sectors, output continued to rise as technological developments meant we could produce more but with less.

The flip side is the extraordinary growth in jobs in Australia’s services sectors. Services now account for around 70 per cent of national economic output. And 8 out of 10 workers in Australia are employed in services jobs.

Services jobs are real jobs. They include our vital health and care workers, our teachers and university lecturers educating young Australians, our scientists and tech workers unleashing the next waves of innovation, and the cleaners, drivers, and administrators who provide the economic plumbing that keeps everything running smoothly.

Despite being an overwhelming majority, these jobs are too often overlooked in public discourse and policy making.

Government responses to economic crises – even services-lead downturns such as the COVID recession – still overwhelmingly emphasise support for the construction and manufacturing sectors. Similarly, government bail-outs, subsidies, and tax breaks for private businesses also weigh heavily toward these sectors.

The rise of services jobs is not something to fight against or bemoan as a country; it is a standard evolution of all countries as they get richer. And indeed, it is expected to continue.

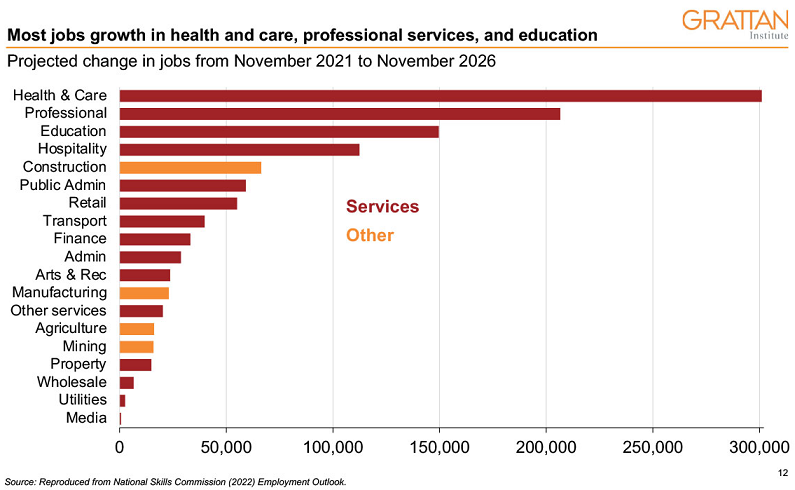

Jobs growth estimates from the National Skills Commission suggest health care, social assistance, professional services, and education will be the biggest growth areas over the next 5 years.

And I think it would be a very fair reading of history and demographics to expect that these trends will continue.

Theme 2: An industrial revolution with a deadline

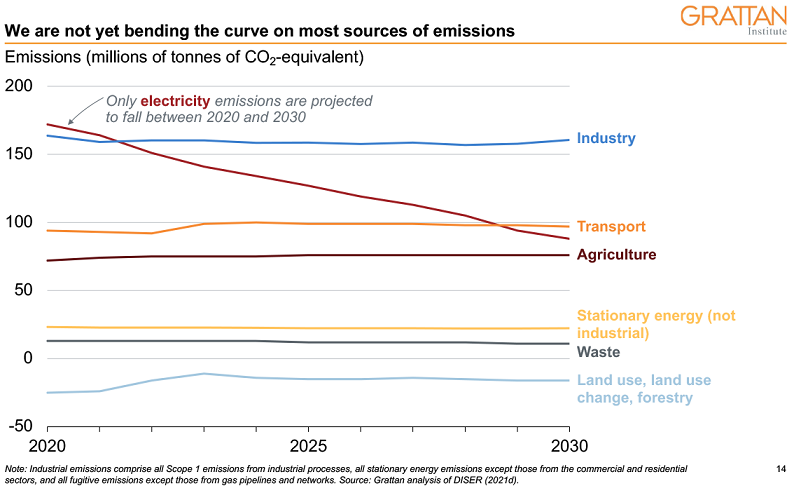

Australia’s economy faces transformative change to meet global and domestic emissions-reduction targets.

Any credible path to net zero means picking up the pace of decarbonisation in the energy sector and starting to bend the curve on emissions in industry, transport, and agriculture over this decade.

We are not yet on that path. Indeed, the latest forecasts suggest that we are yet to shift the dial beyond electricity emissions.

The scale and pace of change required have led my Grattan Institute colleagues to dub it an industrial revolution – on a deadline. But if the challenge is large, so is the opportunity.

Perhaps the clearest way to think about it is a revolution with three fronts.

First, and most difficult, is supporting people affected by the decline of activities such as coal mining that are incompatible with a net-zero economy. The challenge is marrying the phase-out in a way that provides genuine opportunities for workers in the regions such as the Hunter Valley, Mackay, and Collie.

Second, there are existing activities such as steel-making and aluminium production that should be able to transform through low-emission technologies and practices. The transformation of the electricity grid to support significant growth in renewables generation is a crucial part of this shift.

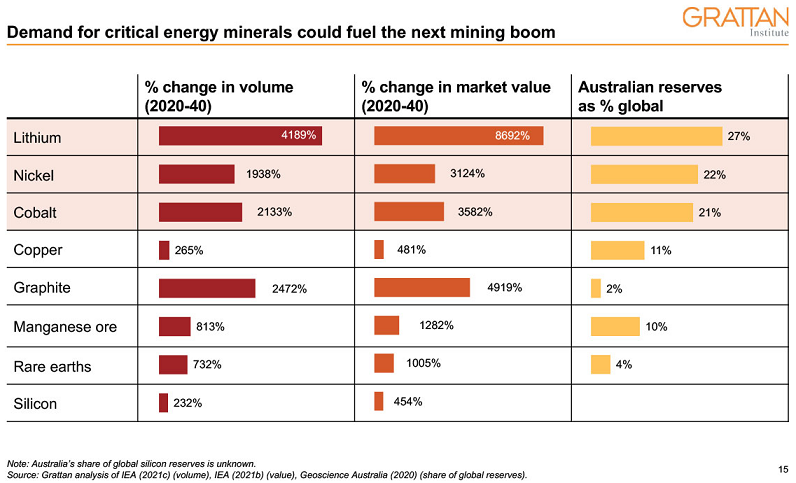

Third, there are the straight-up opportunities. New activities such as low-emissions extraction and processing of critical minerals are small today, but the potential demand is large, and Australia has significant comparative advantages, not to mention large shares of global reserves for important minerals such as lithium, nickel, and cobalt.

Crucially, if we deliver on the opportunities on the second and third fronts, these offer well-paid regional jobs in industries with a sustainable future.

Once again, Australia is the lucky country – we are extraordinarily blessed with abundant supplies of renewable energies and critical minerals. I hope we can today commit to being first-rate leaders who will make the most of this luck to build future prosperity.

Theme 3: The future is digital

The third and final structural trend I want to touch on is the rise of the digital economy.

To date, digital transformation has perhaps loomed larger in our everyday lives than in economic performance, triggering macroeconomist Robert Solow’s quip that ‘we can see the computer age everywhere except in the productivity statistics’.

But there have always been lags between innovation and the economic dividends it can unleash. This is the so-called S curve effect – business simply takes a while to harness the productive capacity of new technologies.

Technologies like AI, data analytics, quantum computing, and robotics continue to develop in leaps and bounds. And bit by bit we are learning how to use them to deliver better and cheaper goods and services. This is why I find myself increasingly aligning with the techno-optimists about the transformative potential of these technologies.

One reason this is so significant is that these technologies have the potential to deliver significant improvements in productivity in services sectors, where it has historically been harder to shift the dial.

From touchscreen ordering in dumplings bars to AI algorithms to prioritise scarce emergency room resources, the use case for these technologies will continue to evolve.

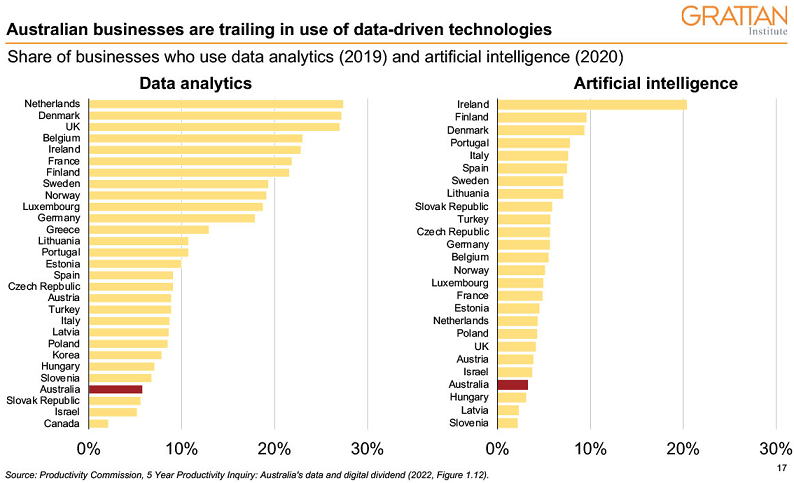

Australia does well in terms of some of the foundations – we compare positively internationally on things like cloud connectivity. But we have much lower adoption of the tools such as data analytics and artificial intelligence that will be critical in driving process improvements.

The most common barriers to technology and data adoption identified by Australian businesses are inadequate internet, lack of skills, limited awareness, and uncertainty about benefits and costs of new technologies, particularly of changing over legacy systems.

Some of these require government investments such as broadband services, cybersecurity, and tech skills – but they also require Australian managers to have the know-how to recognise and respond to the opportunities ahead.

Danielle Wood is the CEO of Grattan Institute, where she heads a team of leading policy thinkers, researching and advocating policy to improve the lives of Australians.

For detailed footnotes, to view the slides, or to read the full address, click here.