In 2008, Shiek Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, estimated worth one trillion dollars and brother of the ruler of Abu Dhabi, bought the football club Manchester City, and threw his wealth into attracting some of the best players in the world. Manchester United had dominated English football for almost two decades, and their manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, responded by calling City a ‘small club’ and ‘noisy neighbours’. But in the quiet of his office, Sir Alex knew that City was now a significant threat.

In many ways, the managed funds industry currently feels the same way about SMSFs as Sir Alex did about City. Like a bulging trophy cabinet, there is now one trillion dollars invested in managed funds in Australia (super and non-super), double the $500 billion held in SMSFs, despite all the headlines that the noisy neighbour attracts. Those other attention-seekers, noisy minnows ETFs, hold only $8 billion, while CBA/Colonial First State alone manages $116 billion in funds.

So the large retail and industry superannuation funds are safe in the knowledge that they are the existing powerhouses of investment and super in Australia, and SMSFs are still the smaller, noisy neighbours. There is as much in the large retail platforms alone as the total in SMSFs. You can be assured that the bonuses being paid throughout the managed fund industry following the strong rise in the sharemarket in 2012/2013 are far from reflecting an industry under siege. From this position of strength, they are trying to respond to the heavily-publicised popularity of SMSFs.

In the 12 months to 30 June 2013 in superannuation assets, industry funds grew by 21% and retail funds by 13.7%, while SMSFs increased by 15.4%. Industry funds continue to attract a massive following, despite the greater product innovation in the retail market. According to Deloittes, retail funds will even overtake SMSFs as the largest segment in super:

“Our projections indicate that the total retail fund sector (that is a combination of retail employer-sponsored and retail personal) will take over from SMSFs as the largest market segment in 2019 and reach almost $2.5 trillion in assets in 2030.”

Useful insights into how the managed fund industry continues to thrive and how investors are thinking can be found in the Morningstar Australian Asset Flows report for June 2013, released last week. Some of the highlights are:

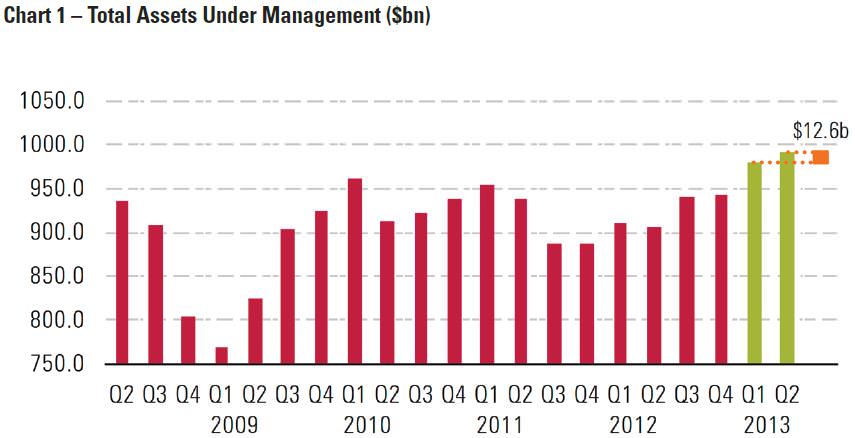

- Total managed funds in the June 2013 quarter rose $12.6 billion to a record high of almost one trillion, a 32% recovery from the $760 billion of early 2009. Global equities did especially well, although most of this was due to market movements rather than new flows.

- In the June 2013 quarter, the expectation of rising interest rates led to outflows from global bond funds, but the total number of -$218 million disguised a major leakage from passively-managed bond funds (-$839 million), suggesting investors have realised that they do not offer protection when rates rise. Actively-managed bond funds did well. There was a rotation out of hedged global funds into unhedged, as investors looked to gain from a declining Aussie dollar.

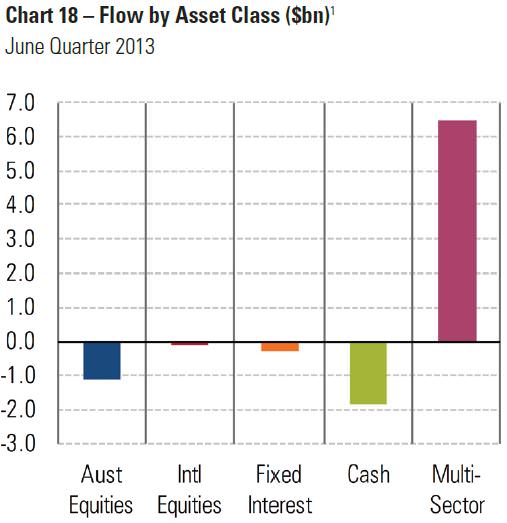

- While there are winners and losers among fund managers and asset classes, there is one segment of the market which shows why managed funds remain a powerhouse: multisector funds. These are the default funds into which millions of dollars of compulsory superannuation flows every day, offered by industry funds and the majority of tied advisers sitting in bank branches throughout the country. Multisector funds dominated flows, raising $6.4 billion in the quarter, with AustralianSuper a massive $1.1 billion alone. AMP took $700 million, although some of this was non-super.

- Multisector funds will always be a bulwark against SMSFs. Regardless of the intentions of the FOFA legislation and Best Interests Duty, the financial adviser employed by CBA in its Parramatta branch, sitting in front of a 50-year-old electrician with $100,000 in super and designing a retirement plan, will reach for the familiar safety of Colonial First State’s platform and its multisector fund. No SMSFs, ETFs, SMAs or external products on the table here.

- The other distinguishing feature of multisector funds is that they do not involve discretionary decisions. They are the funds of the relatively disengaged, who choose a fund or have it chosen for them, and leave it. An estimated 85% of multisector money is superannuation.

- There are 16,000 active managed funds in Australia, and the popularity of individual fund managers ebbs and flows. Putting aside the multisector offers of the major platform providers and their own products, the fund manager winners at the moment are Magellan in active global equities; State Street in global index equities; Alphinity, Bennelong, Investors Mutual and Pengana in Aussie equities; and Kapstream and Perennial in Aussie bonds. Colonial First State was a winner in cash, but the majority was from the Future Fund, managed for a fee of a few basis points.

- The heavy losers in Australian equities are Orion and Solaris. A few years ago both were investor favourites. In global equities, Orbis, Schroder and Walter Scott experienced outflows. The sale of the BT-owned Hastings’ Australian Infrastructure Fund’s assets depressed numbers for the BT Group.

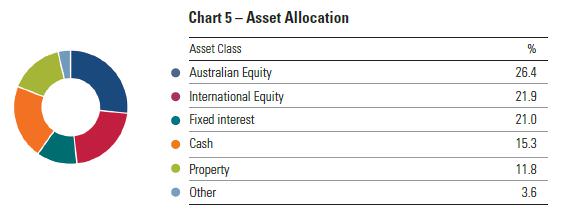

- On asset allocation, with global equities far outperforming Australian equities during the year, and outflows from Australian bond funds, there is greater diversification and less domination by Australian assets than a year earlier.

- Comparisons with SMSF allocations need caution because the latest asset class data is from two years ago. The major asset allocation differences are that SMSFs hold far less in global equities and more in Australian equities (love those franking credits and high yields!), cash and term deposits. Only 14% is held in traditional managed funds.

So what are some of the lessons from the Morningstar statistics?

- Many investors understand that bond index funds – where investments are allocated simply on the basis of where most existing debt is issued and by whom – have no tactical decisions relating to prevailing market conditions, leaving greater vulnerability when rates rise.

- It remains difficult to identify consistent long term manager outperformance, and the fortunes of particular fund managers come and go. While there are certainly fund managers who are more talented than the average, this year’s star is often next year’s chump. This can have adverse implications for loyal investors as managers facing heavy redemptions are forced to create taxable capital gains as they sell down their holdings.

- Comparisons of investment returns by SMSFs versus multisector funds depend far more on asset class allocation than manager selection or stock picking by the self investor. In years when global equities do well (perhaps because the $A falls) and interest rates fall, institutional funds will outperform SMSFs.

- Many managed fund investors are active allocators, not simply passive holders, as the rotation out of hedged global equity funds and exit from passive bond funds shows.

- The managed fund industry is alive and kicking, and regardless of the success of SMSFs, it will be sustained by at least two things: investment returns on the existing trillion dollars, and advisers who support the large platforms putting clients into the multisector funds. And no amount of FOFA, MySuper and Best Interests Duty will change that. Where the large funds are likely to fail is in attracting discretionary money, and retaining retirees once they reach the stage where they want to control their own super and pay less management fees. SMSFs are the likely winners here.

Stretching the Sir Alex Ferguson analogy one more time, he is now retired, leaving United as the reigning champion. The new manager will have a strong team which will always do well, but the opposition is far more competitive, and the noisy neighbours will increasingly attract new fans.

Graphs are copyright of Morningstar and used with permission.