Negative gearing is a phrase used in Australian tax policy debates regarding rental property investments. It is claimed to be a tax concession that an investor receives a tax deduction for interest expenses that contribute to a current loss on a rental property investment and can combine that with wage income for tax purposes. The deductibility of interest for tax purposes, though, is part of the general provisions of the tax act, ie that expenses incurred in earning of assessable income are deductable for tax purposes.[1] So what is the basis of the claim that this is a tax concession?

What is negative gearing?

There are two words in the phrase ‘negative gearing’. The second word ‘gearing’ simply means that borrowing is used in the financing of the investment. The first word ‘negative’ means the current expenses of the investment are greater than its current income. That is, the investment is making a loss in the current financial year (with a presumed accruing capital gain). So, a negatively geared investment is one that uses debt in its financing and the current expenses are greater than the current income.

While the tax policy issues around negative gearing are relevant to any taxable investment, the negative gearing phrase is typically used for rental properties investments. The expenses consist of interest on a loan and other costs such as property maintenance, depreciation and other taxes – all deductable in the current financial year. The returns can be categorised in two parts: current income in the form of rent, which is taxable in the current financial year; and an accruing capital gain, which is taxable only upon sale of the property and generally with a 50% discount.

While a rational investor will expect to make a positive return over the life of an investment, that can be consistent with making a loss in the current financial year (current income minus current expenses), with the accruing capital gain expected to turn that into a positive overall return.

The second aspect of the negative gearing tax policy debate is that current losses on investment income are generally able to be combined with an individual taxpayer’s other taxable income, eg wages. This is consistent with the general schema of the Australian tax system whereby in a progressive income tax system an assessment of a taxpayer’s overall ability to pay is required.

A taxpayer’s net income for the year is taken as a proxy for assessing their ability to pay tax. In the Haig-Simons[2] tradition, a comprehensive measure of net income is required to establish a good basis for assessing a taxpayer’s ability to pay tax – all income, regardless of source, form or use, should be included. Combining an individual’s capital income and labour income is what is required to assess their comprehensive income and ability to pay tax.

Rental property investments

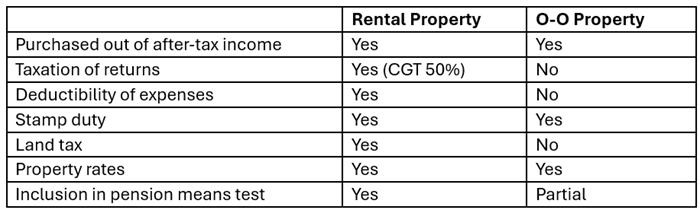

Within the property market, it is important to understand the differences between the tax (and transfer system) treatment of investments in rental properties and in owner-occupied properties. For a given overall supply and demand in the private housing market, it is the split between these two that is fundamentally at stake.

Owner-occupied properties are generally treated more concessionally in the Australian tax/transfer system than rental properties. With owner-occupied properties, neither the imputed rent[3] from living in the house nor the capital gain upon sale are taxable. With rental properties, there is full taxation of rents and partial taxation of capital gains. Consequently, no tax deductions are allowed for owner-occupied property expenses while full deductions are allowed for rental properties.

Further, while purchases of both rental and owner-occupied properties are subject to stamp duty and both pay property rates, land tax applies to rental properties but not owner-occupied properties. In addition, owner-occupied properties are largely exempt from transfer system means tests.

Taxation of Rental v Owner-Occupied Properties

Overall, the existing tax/transfer system in Australia is heavily tilted in favour of owner-occupied housing.

Is negative gearing a tax concession?

Whether something is a tax concession needs to be assessed against some benchmark of an ideal treatment. Departures from that ideal benchmark might be considered concessions (or penalties). The general benchmark for income tax in Australia is net nominal income. The Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement adopts a comprehensive measure of income (labour and capital) and provides for deductions for expenses incurred in earning that income.

Consistent with this, the Income Tax Act states “your assessable income includes the ordinary income you derived directly or indirectly from all sources”[4] and that you can deduct from that, expenses “incurred in gaining or producing your assessable income”.[5] That is, the benchmark for the general schema of the Australian income tax law is net nominal income.

To assess the tax treatment of negatively geared investments in rental properties against this benchmark, we can first examine the expense and income sides of the transaction separately, then consider any asymmetry between them.

On the expense side, there is nothing unusual about the tax treatment of investments in rental properties. Expenses incurred in earning assessable income are deductable under the general provisions of the income tax act and this is the treatment applied to expenses for investments in rental properties.

On the income side, though, there are two components: rent and capital gains. Rent is treated like other current income; it is included in the taxpayer’s assessable income for that financial year. Capital gains, however, are treated differently. While an ability-to-pay approach in the Haig-Simons tradition would call for the accruing capital gain to be included in each year’s assessable income, akin to how depreciation on assets is allowed as a tax deduction annually, the general practice is to only apply capital gains tax upon sale of the asset. Further, only half the nominal capital gain is included in assessable income for that year.

It can be seen, then, that there is an asymmetry in the tax treatment of the expense and income sides of rental properties investments. The expense side of the transaction is consistent with the nominal income benchmark. The income side of the transaction, though, is not. From a benchmark perspective, then, to the extent there is a tax concession associated with investments in rental properties, it has nothing to do with the deduction of interest (negative gearing), it is about the income side of the transaction and the tax treatment of capital gains. Importantly, this is the case whether the property is negatively geared or not.

It can be argued, then, that the capital gains tax treatment of investments in rental properties, as with other appreciating assets, is concessional. As such, any reform of the tax treatment of rental properties is best considered in the broader context of reform of Australia’s general approach to the taxation of capital income.

Second best?

Reforming capital gains tax, though, is a difficult task. With the 50% discount, it can be argued that this is a (generous) proxy for an inflation adjustment. With the deferral of the taxing point to sale, it is claimed an accruals approach presents valuation and cash flow difficulties.

So, if capital gains tax reform is not possible, a ‘second best’ argument might be made for an offsetting distortion on the expense side of the transaction. That is, some restriction on the tax deductibility of expenses such as interest could act as an offsetting distortion to the under-taxation of capital gains.

This approach would achieve greater symmetry between the tax treatment of the income and expense sides of rental property investments. A better approach, though, would be to address the under-taxation of capital gains directly.

Consequences of increasing taxation of investments in rental properties

While assessed against the standard income tax benchmark, negative gearing is not a tax concession, it is worth examining what the consequences would be of an increase in the taxation of investments in rental properties if that step was taken.

Such an increase in the taxation of rental properties investments would add to investors’ costs, tilting the balance further in favour of owner-occupier purchasers. For a given overall supply of housing, an increase in the taxation of rental property investments would likely mean there would be more owner-occupier properties and less rental properties - at the margin some renters would become owner-occupiers.

While the tax increase on rental property investments falls initially on investors, they will seek to pass that through to tenants in higher rents. There is a distinction between the legal and economic incidence of taxes – the rental property investor has the legal incidence of the tax increase, but they will seek to pass the actual economic incidence of that tax increase onto the tenants.

The extent to which they can do that will depend on the relative market power of the landlord and the tenant. The lower their market power, the greater will be their share of the tax increase. In a tight rental market, tenants have limited alternative accommodation options, and it is likely they will have relatively low market power. Keeping in mind this is a tax increase on just one asset class, investors have other investment opportunities to achieve their required after-tax rate of return.

The consequence of a policy action to increase the taxation of rental property investments would be a reduction in the quantity of rental properties and likely some increase in rents. Conversely, there would be an increase in the quantity of owner-occupier properties. The magnitude of these changes would depend on the size of the tax increase and the realities of investor/tenant market powers.

Policy lessons

There are some major problems in the Australian tax system, including ones that impact on the housing market, that are sorely in need of reform efforts. The taxation of capital income generally is a mess, with investments in properties, shares, superannuation and bank accounts taxed in markedly different ways. Further, the use of structures such as companies and trusts to minimise tax obligations is compromising the integrity of the Australian tax system.

Increasing taxes on housing is not the way to increase supply. In the housing market, the most obvious tax reform initiative is at the state and territory level with a transition away from stamp duty (a transaction tax) to a broad-based land tax (a recurrent tax).

The negative gearing discussion is an unfortunate distraction from more genuine tax reform priorities.

[1] Contrary to some public perceptions, there is no ‘negative gearing’ provision in the tax law.

[2] American economists who developed a measure of income for tax purposes.

[3] The equivalent of the actual rent paid by a tenant in a rental property. This was part of Australian income tax law from 1915 to 1923, and still applies in some OECD countries.

[4] Income Tax Assessment Act 1997, s6-5(2).

[5] Income Tax Assessment Act 1997, s.8-1(1)(a).

Paul Tilley is the author of Mixed Fortunes: A History of Tax Reform in Australia. He is a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, and a Senior Fellow at the Melbourne Law School.