In a former life, as a financial planner, I counselled my clients to consider the benefits of Total Return Investing (TRI). Forget about income, I said. Trust the academics, and the professionals (me). Today, however, I’m not so sure. TRI may in fact be doing investors a disservice. I say that because the global investment landscape has changed, and so have the risks.

The TRI theory holds that investors should build and learn to live off the total return of their portfolio, not just the income. In practice, this means investors sell appreciated assets when they need income above what is generated by the portfolio. And, where possible, live off dividend and interest income in the years when the portfolio declines.

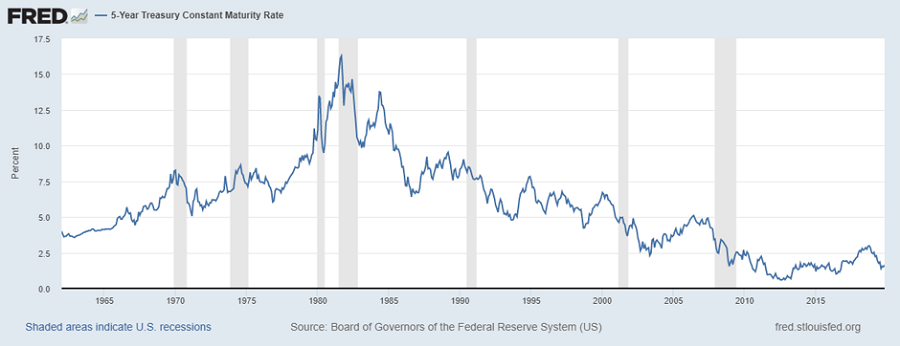

The Total Return approach is elegant, it makes intuitive sense, and like so many investment strategies, it ‘backtests’ well – that is, it’s done well in the past. There is, however, a fly in the ointment: the prevailing global low-to-no interest rate regime. The backtests in the U.S. occurred during periods when both stock and bond yields were much higher.

5-Year U.S Treasury yield (1963-2019)

Thus, the TRI theory is based on what we now know to be the luxurious presumption of earning income from fixed interest. No one has had the experience of funding a 30+ year retirement through a period of zero or even negative interest rates.

The short income squeeze

This lack of income is a critical weakness of TRI theory because the less income your portfolio generates, the more you are exposed to the pain of calling on your principal during market drawdowns - what I term a “short income squeeze risk”.

Here’s how it works: in the event of a market downturn, a lack of income creates, in essence, a short-squeeze situation. Retirees have no choice but to sell their investments and often at times when valuations dictate they should be buying or at least holding.

To date, this danger has been easy to ignore because returns have been strong and volatility relatively benign. However, there are reasons to believe it may not be in the future.

The new risk hierarchy - consistency of income trumps portfolio volatility

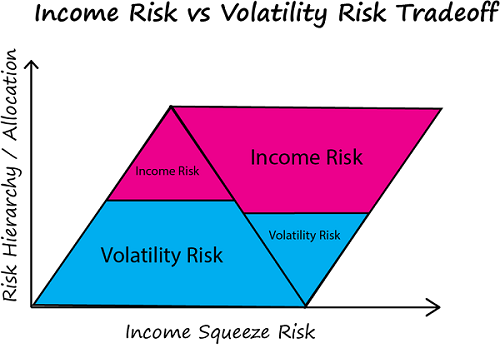

Intelligent investors think in terms of risk and then return, so it may be helpful to rephrase the issue in terms of a hierarchy of risk. In the past, the risk of an income squeeze could be easily subordinated to the risk of portfolio volatility because income was readily available. Today’s environment calls for a rethink.

I contend that below a certain portfolio income threshold, maintaining a steady income is a higher priority than minimising volatility. This threshold will depend on several factors which may include:

- the degree of spending flexibility

- capital risk relative to income

- diversification considerations, and

- other sources of funds.

The degree of capital risk assumed relative to income obtained is also a critical consideration. Investors and their advisers should examine this new retirement risk landscape and re-calibrate their portfolios if necessary.

Sustainable income – mitigating income squeeze risk

One strategy to mitigate income squeeze risk is to increase the portfolio allocation to investments that offer sustainable dividends. Specifically, companies and credits with stable business models that rely on secular growth trends, such as population growth both in Australia and abroad.

The classic rejoinder to such advice is that it entails foolishly 'reaching for yield', i.e. unknowingly increasing risk by moving from lower- to higher-risk assets. And it is true, increasing your allocation to riskier assets will raise the volatility of your portfolio.

However, the paradoxical world created by low-to-no interest rates means that the income generated by equity-like dividends may come to be the only way to shelter retirees from an income squeeze. And as a result, spare them from having to erode their principal during a severe or even moderate downturn.

Thus, it can be argued that by taking more risk, you are making the conscious decision to reduce income risk (the income squeeze). The choice then is not a reach for yield but the inevitable by-product of all investment decisions, the exchange of one type of risk for another.

Recognising this, Legg Mason has created income solutions like the Legg Mason Martin Currie Equity Income and Legg Mason Brandywine Global Income Optimiser which are designed to invest in assets that hold out the prospect of providing sustainable income. As central banks continue to consign investors to a world without income, we believe these strategies will play an increasingly important role in clients’ portfolios.

Peter Cook is a Senior Investment Writer at Legg Mason Australia/NZ, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article contains general information only and should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Please consider the appropriateness of this information, in light of your own objectives, financial situation or needs before making any decision.

For more articles and papers from Legg Mason, please click here.