Celebrating its 15-year anniversary, Realindex Investments has changed its name to RQI Investors. RQI manages close to $30 billion through active, quantitative strategies. Here, Firstlinks’ James Gruber interviews RQI Investors' Chief Executive Andrew Francis and Head of Investment Dr. David Walsh about how the firm is meeting today’s market challenges.

James Gruber: How would you describe your approach to investing as a firm?

Andrew Francis: Our approach to investing is quantitative. That means that we're very systematic in our approach to research, portfolio construction, our processes are very quantitative in nature. But we don't believe the market is perfectly efficient and we think that by generating quantitative insights, we can outperform the marketplace.

Gruber: Has passive investing changed the way you invest across time? For instance, with value, has it increased the opportunities or decreased them?

Francis: I think the duration of some cycles is longer than it might have been in the past. The weight of money going into some parts of the market can mean that that mispricing might stay mispriced for slightly longer than it might have in prior years. But there's still long-term mean reversion.

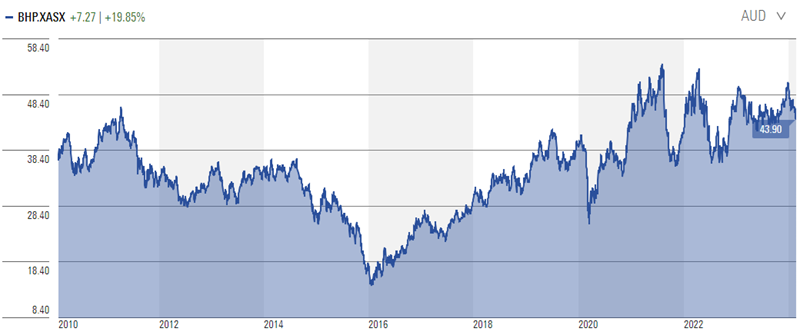

Take for example, BHP. In 2010, BHP was ‘stronger for longer’. It was perceived as a resource super-cycle with China going to the moon and back in terms of growth. But the cap weighted index was putting more and more money into BHP at that point of time. I think it got up to $45 or $50, representing 12% to 14% of the Aussie market.

And everyone would say, but you're underweight BHP. And I said, yes, we are underweight BHP. And they said, well, you will never be overweight BHP. And I said, well, I don't know. And that was the truth.

But you know what? It wasn't a resource super cycle. China wasn't stronger for longer. And we saw BHP share price go from that $45 down to $15.

Source: Morningstar

And you know what happens at $15? Charlie Munger says that the share market is the only market on the earth that no one wants to buy when it's on sale. And the point is: you had a maximum amount of money, if you're invested in a cap weighted index, in BHP at the peak of the market. And when it's down at $15 and it's cheap, no one wants to buy it. And it's half the index weight.

Well, you know what? When you're weighting by fundamentals, our weight didn't change considerably. So, we were very underweight BHP when it was at $45. And we were rebalancing back to company fundamentals and then when it was down at $15, our weight hadn't changed significantly, but the market cap weight had changed significantly. So, all of a sudden, we're very overweight BHP and we've benefited from the mean reversion on the way down to $15 and on the way up as well. This example highlights the value process in that one name. And we can give countless examples as well.

Gruber: We'll get David in here. Systematic investing, it looks for edges in things or asymmetries in data and markets. Do you find that those asymmetries persist, or do they evolve, and you have to change into other asymmetries over time?

David Walsh: A lot of good ideas can be arbitraged out over time. This is well-known in the market - that certain things come on and they're researched, and then there's more and more people tending to chase those ideas which can be arbitraged out. We do see that.

But the question you have to ask in the first place is: why do these inefficiencies exist? And we believe there are some three central reasons why they do that.

- There are limits to arbitrage including not being able to act fast enough, and costs in terms of opportunity sets.

- There are behavioral biases: people behave in a certain way that means they're underreacting to news, they tend to oversell, don't sell at the right times, or buy at wrong times.

- And information complexity which includes the vast amount of information flowing at the moment.

So those underpin a lot of the inefficiencies in the market, they're not changing, but getting worse in a lot of ways.

The question then is not ‘does a particular insight get arbitraged out?’, it's ‘can you exploit one of those three ideas in a way in which you can generate alpha’? It might be that one particular idea gets arbitraged out, but an idea which replaces it, which has a bigger barrier to entry, is more complex, remains. The trick is in your research and the way you build models to capture those ideas in a more efficient way. The fact that these ideas can be arbitraged out is more a mechanism of the way in which the market prices it. It could be the data that's available becomes more commoditized, it could be that the research becomes more popular in academic publications, those sort of things cause it. But the underlying fundamentals to why markets are inefficient don't really change.

Gruber: Do you rely 100% on your models or is there some human judgment that comes into play?

Walsh: All our best ideas should be in the models. We don't override the models once they’re in the portfolios, unless there are extreme circumstances. The human part comes in the research and generating the ideas in the first place. The idea has to be generated by insight and really at the core of what we do is better insight. We need to be very good at building the right team, having the right environment and the right culture to foster insight development. Now when you're doing that, you're involved in a lot of discussion with the team, a lot of research, sometimes subjective decisions, sometimes not. You spend a lot of time researching your ideas and building better tools so you understand what's going on. When you build the model and put it in place, you’re confident it is going to work. At that level, the subjectivity is gone. In some sense subjectivity comes in when you're doing the research in the first place and how you go about choosing it and what the ideas might be.

Gruber: ESG has copped a fair bit of flak of late. It's always been part of what you do. Has that changed your view on ESG at all and how you do things?

Walsh: We've got a philosophy around ESG we think is consistent and hasn't changed. The consistent idea is ESG should fall into one of, we think, four pillars of ideas – exclusions, company engagements, risk controls and alpha sources. Exclusions are stocks you don't want to own at all, which are usually based on client mandates. And from time to time, we'll put in exclusions ourselves based on our own principles, for example, tobacco and controversial weapons won't be included.

We also do an engagement process with companies over time, which is significant. Being a quant manager, we own a lot of stocks, so it can be hard to engage with all companies. We've got to be very selective who we engage with.

But when it comes down to it, the key issues we see in ESG are firstly risk controls, controlling what we perceive to be an ESG risk; carbon exposure being a good example of that.

And secondly is around alpha sources. Now ESG as an alpha source, it's something of an anathema with quant managers because they don't necessarily see it that way. But we would say that ESG is a reflection of a good quality company. A company which has good ESG policies, implements efficient ESG in what it does is a better quality company. So, it gives you a lens on how a company operates. In a sense, ESG alphas are a way of thinking of quality within a stock.

Francis: I might just add one thing on the ESG alpha side. Likewise, if we didn't have comfort on those signals, they wouldn't make their way into the portfolio. They've got to stand up on their own right. They're not there because they're ESG. They're there because we think they've got a competitive advantage versus other signals and they're complementary. But if, for example, we lost confidence in any of those signals, they wouldn't make up part of the portfolio.

Gruber: And how are you going about that with AI and trying to implement that in your firm going forward?

Walsh: We have a really strong team that understands a lot of this work in terms of natural language processing or other various machine learning applications, but we're really very hesitant to put something in unless the insight is right. So, the insight needs to be there. The machine learning, AI, natural language processing is not the insight. That's not the idea. It's a tool to apply a certain level of insight. And maybe you can have insights or see things going on the data you can't see normally without applying some kind of other tool like a machine learning or natural language processing, deep learning tool of some sort that will give you those. So, we have approaches which use natural language processing and text processing for alphas. We use machine learning in a way that we think of selecting peers between groups, so how does momentum work between peers, how do you choose a peer group? Those sorts of things require machine learning tools. But the idea is what comes first.

Andrew Francis is the Chief Executive and Dr. David Walsh is Head of Investment at RQI Investors, a wholly owned investment management subsidiary of First Sentier Investors, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

For more articles and papers from First Sentier Investors, please click here.