Superannuation tax concessions have been the subject of considerable public debate in recent times. The debate is likely to be fuelled again by this week's release of draft legislation for a new tax on investment earnings for total superannuation balances above $3 million.

The legislation and commentary around it suggest that the current tax arrangements for superannuation are unfair and/or unsustainable.

This article tackles this issue from a different perspective. That is, are there long-term financial benefits from the tax concessions for individuals and the government?

But let’s begin with an analogy.

It's not super versus Age Pension

Many Australians own an investment property. The annual expenses relating to this investment include borrowing costs, maintenance, land tax, council rates and insurance which may exceed the income received from their tenants. However, their investment is for the long term and any short-term negative cashflow is an investment for the longer-term benefit.

Superannuation tax concessions should be considered in a similar way. That is, taxpayers (through government policies) are investing for the longer term, in line with two broad government objectives. The first is to enable Australians to have a dignified retirement and the second is to reduce future Age Pension costs.

Hence, we'll look to address the following question:

Does the government’s investment in superannuation provide a fair outcome for individuals and improve the government’s future fiscal position?

This longer-term holistic approach also highlights the inappropriateness of comparing today’s Age Pension costs with the level of superannuation tax concessions for future retirees. These two forms of government support are given to different generations for different purposes. There is no reason why one should be higher or lower than the other.

The base case: a median income earner

Consider an individual on the current median income of $65,000 and subject to a marginal income tax rate of 34.5%, including the Medicare levy.

Assume this worker receives an SG contribution of 12% throughout their career of 40 years and will have a retirement period of 25 years from the age of 67. We will also assume that at retirement, the individual will convert their accumulated superannuation benefit into an account-based pension, which represents the most popular retirement product in Australia today. We will also assume that the retiree withdraws money from their account-based pension using the minimum drawdown rules which apply from 30 June 2023. Again, this represents the behaviour of many retirees who have a reasonable superannuation benefit.

We will compare this superannuation scenario with a non-super counterfactual. That is, the government continues to require a savings rate of 12% but provides no taxation concessions so that these savings are taxed at the individual’s marginal tax rate. The resulting investment income would also be taxed but at a slightly lower rate to allow for the capital gains discount and franking credits. During retirement, the retiree would again withdraw money based on the minimum drawdown rules.

Under both scenarios, the retiree may receive a part or full Age Pension, subject to the current income and assets tests, with the thresholds indexed to CPI.

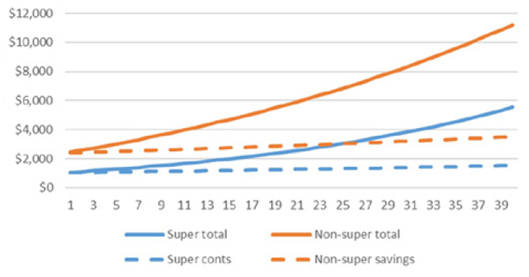

Figure 1 shows the actual tax paid during the 40 years of active employment, from both the superannuation and non-super scenarios. The numbers have been deflated by CPI to express them in today’s dollars. The top solid lines in Figure 1 represent the total tax paid each year while the lower dashed lines show the tax paid on the super contributions and the saved income respectively. The difference between the solid and dashed lines represents tax paid on the investment earnings which naturally increases as the balances grow over time.

Figure 1: The real value of tax paid each year

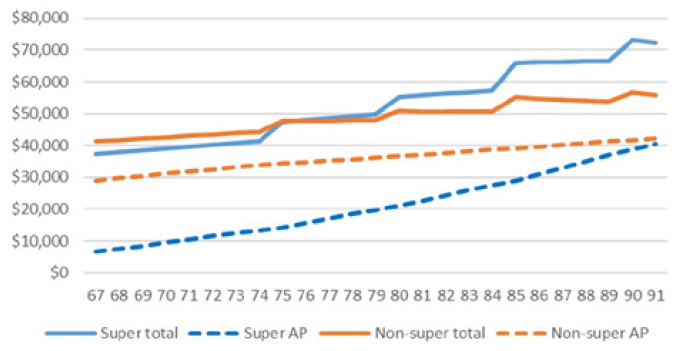

Now let’s turn to the retirement years. Figure 2 shows the total income and Age Pension received each year, again deflated by CPI, to express it in today’s dollars (AP=Age Pension).

Figure 2: Real income during retirement

Several observations are worth making.

- The Age Pension (AP) paid under the non-super scenario is higher than under the superannuation scenario due to the lower level of financial assets.

- The Age Pension payments increase materially during retirement under the superannuation scenario as the superannuation balance is gradually reduced. This outcome highlights the impact of the assets test on the Age Pension.

- Due to the impact of the assets test, the total income in the super scenario begins below the income in the non-super scenario but overtakes it at age 75 due to the impact of the increasing Age Pension.

- The total income received is jagged under both scenarios due to the impact of the minimum drawdown rules.

Finally, and not shown in the graph, is the capital available at age 92 under the two scenarios. In today’s dollars, the balances are $274,150 and $162,822 for the super and non-super scenarios respectively.

The real value of all the future income in retirement plus the remaining capital at age 92 under the superannuation scenario is 23.1% higher than the real value of the future income and remaining capital under the non-super scenario. This represents a good outcome for the individual with superannuation.

But what about the cost to the Budget?

However, the question remains: How much did this positive outcome for the retiree with superannuation cost the government?

The costs to the government include the superannuation tax concessions shown in Figure 1 as well as the limited income tax during the retirement years, in contrast to the income tax that would be paid under the non-super scenario. However, these concessions must be offset against the extra Age Pension payments paid under the non-super scenario shown in Figure 2.

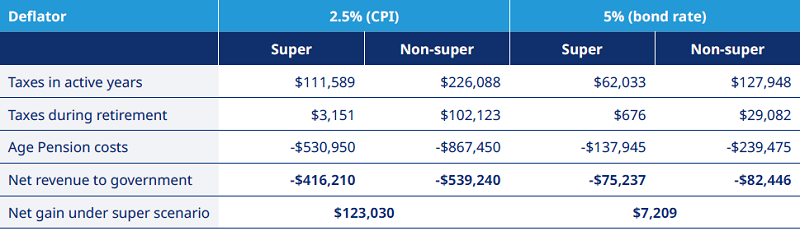

Table 1 shows the government finances under both the super and non-super scenarios allowing for future Age Pension payments and the tax received during both the pre-retirement and retirement years. These future cash flows have been deflated in Table 1 at both the assumed CPI rate of 2.5% and the assumed long term bond rate of 5%.1

Table 1: The net present value of future cash flows between the government and the individual

These figures highlight:

- The most significant cost to the government relating to the provision of retirement income for a median income earner is the Age Pension.

- This cost is significantly reduced by the presence of superannuation.

- There is a net gain to the long-term government finances under the superannuation scenario, both in real terms and when the bond rate is used as the deflator.

- The income tax paid during retirement is higher under the non-super scenario as both the investment earnings and the Age Pension are subject to tax.

- As expected, the present value figures are much lower when a higher deflator is used.

In sum, the superannuation scenario provides a better long term financial outcome for both the individual and the government than the non-super counter-factual.

Of course, there are many different scenarios for different income levels, though most of them also show a similarly favourable outcome for the superannuation scenario for both individuals and the government. These scenarios and their assumptions can be found in the full report here.

Tax concession improvements

Many government reports, including the Henry Tax Review and the Retirement Income Review, make the case that superannuation should be supported by the government through tax concessions and not be taxed in the same way as other forms of saving. However, that is not to say the current arrangements are fair or appropriate.

Our recommendations for improvement include:

- reducing the taper rate of the assets test of the Age Pension from $3 per fortnight to $2 per fortnight.

- increasing the current minimum drawdown rates for pension products by 2% to increase the level of drawdown during retirement.

- maintaining the current concessional contributions cap, as it should be no less than the required SG contribution rate on the maximum super contribution base.

- halving the current non-concessional contribution cap or introducing a lifetime cap for non-concessional contributions.

- reducing the threshold for the Division 293 tax from $250,000 to $225,000 (or 20% above the top marginal income tax rate).

- introducing the additional tax on investment earnings for balances above $3 million while ensuring that this cap is always greater than or equal to the indexed transfer balance cap.

Dr. David Knox is a Senior Partner and Senior Actuary at Mercer Australia. This article is general information and not investment advice, and does not consider the circumstances of any person. Mercer's full report "Rethinking super tax concessions" can be downloaded here.