For many years, much has been written about the apparent complexity of hybrids and how they should not be sold to retail investors. The outgoing ASIC chairman, Greg Medcraft, last week went as far as saying they were a ‘ridiculous’ product for retail investors.

However, in the last five years or so of hybrid bashing, I have never seen anyone suggest that retail investors should be banned from investing in equities issued by the same companies. Equities are more complex with many more moving parts for the average punter to comprehend. Compared with hybrids, equities are significantly more volatile and are far more likely to experience a rapid fall in value, dilutionary equity raisings, reductions or complete cuts of income (i.e. dividends) and even a complete loss of value. While the downside of equities can be significant, the trade-off is there is no limit to the upside.

As an analyst, I work in probabilities and facts. Yes, the hybrid (and equity) prospectuses can be complex to read, however, when it is boiled down there are five simple questions that cover the majority of scenarios.

Five questions to ask

1. Is the hybrid issued by a regulated bank or insurance company?

Banks and insurers are preferable issuers as there is the added protection of a regulator monitoring the company and a defined set of rules, which govern the disaster scenarios.

Moreover, banks and insurance companies have reputations to uphold and as regular issuers of debt, they do not want to let investors down as it will cost them in higher margins next time. Further, they are typically rated by one or more agencies. With corporate hybrids, on the other hand, I always assume the company will do what is best for the company, not the investor.

2. Will I get paid my quarterly distribution?

There is approximately a 99% chance of payment. The main concern is how hybrid distributions can be cut if ‘this, that or the other’ happens. However, to my knowledge, no Australian major or regional bank or insurance company has missed or even deferred a coupon on any hybrid in the past 20-odd years. For highly-rated banks and insurance companies, I assign a probability of a missed coupon at less than 1% on a five-year horizon.

Another way to assess the risk of income loss is to ask, “do I think the company will cut their share dividends to zero at any point in the next five years?” Practically all hybrids have a ‘dividend stopper’ which says if the company misses paying a hybrid coupon then they are not permitted to pay a dividend to shareholders. For large banks, insurers and corporates, the prospect of not paying a dividend would be a last resort and a significant deterrent. If a company is paying dividend, it must pay all hybrid distributions – a very simple test.

3. When will I get my money back and how much will I get back?

There is around a 95% probability of full capital return at first call date and 98-99% probability of full capital return by mandatory conversion date.

Once again, much has been written about call risk and the prospect of being converted into equity, potentially at a loss of capital. Talking facts and probabilities, to my knowledge all Australian major and regional banks and insurance companies have called/redeemed when expected for at least the past 10 years. In almost all cases, this is the first possible call date.

Further, no Australian bank or insurer has been forced or chosen to convert hybrids to equity under the new Basel III regime. Regulations and capital buffer requirements are far more stringent since the GFC, a crucial fact that is often missed in the discussion about the risk of hybrids.

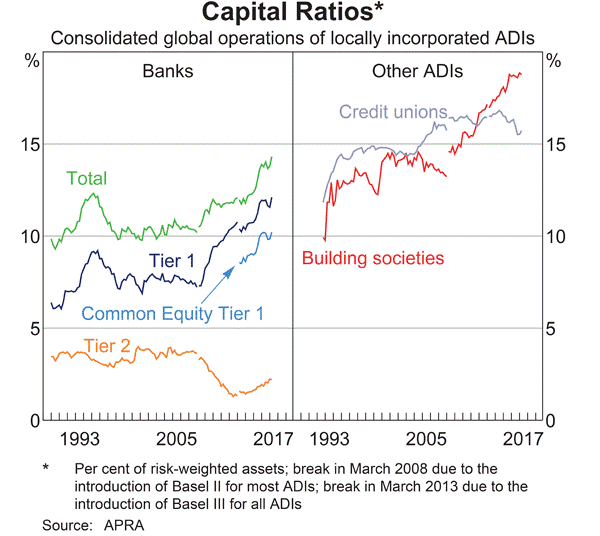

Last week APRA released their ‘Unquestionably Strong’ capital requirements for Aussie banks. Once fully implemented in 2020, some local banks will have almost double the capital buffer compared to pre-GFC levels (and many of the world’s leading banks have close to three times the capital from pre-GFC levels). This is capital that ranks below the hybrid level and is used to absorb losses before impacting hybrid investors.

The risk of default by all hybrid securities has been massively reduced, due to the enormous build up in common equity capital buffers, and the huge importance placed on this capital. Monitoring of early warning signs by the regulators such as APRA (arguably the world’s best regulator) also lower the risk of default. Bank and insurance boards’ desires to have an adequate buffer over the minimum requirements have reduced the risk of default for all hybrid securities.

Capital ratios for Australian banks

For the new-style/Basel III compliant mandatory converting hybrids issued by the major banks these days, I assign the following approximate probabilities:

- 95% chance of call at first opportunity.

- 3-4% chance of conversion into equity two years after first call.

- 1-2% chance of an unexpected outcome such as continuation or conversion to equity later than the scheduled conversion date, conversion into equity at a loss or default.

Would an equity investor refrain from buying a particular share if there was a 1-2% chance of a delay or risk in receiving back the initial investment amount?

Like most debt securities, hybrids issue at $100 and redeem at $100, and the value can vary in-between (in the vast majority of cases no higher than $110 and no lower than $90). Ideally, we look to buy hybrids at a discount when the opportunity arises to counteract the ‘no upside like equity’ argument.

Granted there are a few apparent exceptions that have gone past their call dates such as NABHA, MBLHB and SBKHB. However, these were not sold with the expectation they would be called at the first opportunity. They were different due to a unique set of regulatory and tax rules that existed for a short period in the late 1990s when they were issued. It is these ‘legacy’ issues (which in my estimation account for just ~1% of all hybrid issues in the past 20 years) where investors may need some help from industry experts. The ANZPCs could also be considered an exception. While we expect them to be called in September 2017, they fall into the 3-4% that may go to the conversion date.

It is the 1% of ‘different’ hybrids that tar the other 99% with the ‘complex’ brush. However, it is the misunderstood securities that present the best opportunities if time is taken to understand them.

4. Can I live with potential volatility?

The main risk of hybrids is they can be volatile in times of stress. In the GFC, some major bank hybrids fell circa 30%. However, bank share prices fell double that. I expect the fear of conversion into equity under Basel III from a predominately retail investor base would likely see some material price falls in times of extreme stress, but therein lies a potential opportunity.

As a rule of thumb, I assume that in a stressed environment such as the GFC, hybrids will fall around half of the decline of the underlying equity. Unfortunately, the Australian dollar hybrid market is now almost exclusively floating rate notes, which do not benefit from falling yields in a crisis scenario.

For investors who cannot afford to hold until expected maturity or call date or until the price recovers, this may be an issue. Further, if the volatility of hybrids is unacceptable, then the volatility (and significantly higher risk to income) of equities should also be unacceptable.

5. Am I being paid for the risk?

Typically, a hybrid pays two to three times a term deposit return for arguably a minor increase in default or missed income risk (in probability terms).

The main risk is volatility in times of stress, not credit risk. Hybrids provide better risk-adjusted returns versus sub-investment grade or unrated corporate bonds with similar yields or margins.

All investment decisions come down to ‘am I being paid enough for the risk I am taking?’. Comparing hybrids to term deposits needs to recognise the extra return for the risk.

Assessing the risks

The key to assessing the risk is to consider:

- Probability of default, and

- Loss if a default occurs

The massive increase in capital buffers and regulatory oversight in the past decade has de-risked bank and insurance hybrids. Yes, there are provisions to cancel coupons, defer expected maturity/call dates and convert into equity (potentially at a loss) but these risks are minimal, especially for best of breed, highly rated APRA regulated banks and insurance companies.

The much-feared ‘conversion into equity or point of non-viability (PONV)’ clause in the new style hybrids is unlikely to be triggered. I would argue that whether under the old regime that existed at the time of the GFC or the new Basel III PONV rules, if a bank has capital so low that the regulator has to step in, the value of the hybrid Tier 1 capital (and the Tier 2 subordinated debt capital) at that time would be less than 10% and most likely close to zero.

For major banks, I assume less than 1% chance of default and a zero recovery in that unlikely event.

Compare that to sub-investment grade or unrated bond issues from small companies. For example, a single-B senior unsecured bond has a historical probability of default over a five-year period of around 18.5%. Loss given default is dependent on the facts but would typically be 80% to 100% loss for anything with a material amount of senior ranking bank debt, especially for a ‘cashflow lend’ to a company with few hard assets.

Investors need to be aware of what could happen, but the investment decision should be based on what is expected to happen i.e. probabilities.

Not a good time to buy hybrids

While we are comfortable with the risk/reward dynamics of the new-style bank and insurance hybrids, the current returns from bank and insurance hybrids on an outright basis are on the expensive side. The yield to expected maturity/first call are around 6-7% or trading margins in the mid-300 basis points (3%). Our general rule of thumb is that five-year hybrids are good value when trading margins are closer to +500 basis points (5%) and fair value at around +400 basis points.

Corporate hybrids and hybrids from non-Australian banks and insurers are more complex and do require additional analysis to understand the market and regulatory drivers.

Justin McCarthy is Head of Research at Mint Partners Australia. The views expressed herein are the personal views of the author and in no way reflect the views of the BGC Group. Individuals should make investment decisions based on a comprehensive understanding of their own financial position and in consultation with their own financial advisors, and no responsibility is accepted for the opinions in this article.