This is an edited transcript of a webinar hosted by Schroders. Part I features Natalie Morcos, Head of Product, Solutions, and Client Service, with Martin Conlon, Head of Australian Equities. We’ll have Part II next week.

Natalie Morcos: Martin, I'd like to really just start off by setting the scene. We're at a multi-decade turning point in inflation. We've seen the sharpest rise in interest rates. And this reporting season has been touted as being one of the most interesting. What can you share with us and how are you responding to this current season?

Martin Conlon: Thanks Nat. Well, I'd start by saying that turning point issue you raise is potentially, in our eyes, one of the most interesting. And the reason I say that is that bond markets have changed pricing pretty aggressively over the last year or two. And you can now get 4% yields on treasury bonds in the U.S. and 10-year government bonds in Australia. Interestingly, that is … signifying a fairly different outlook on the future.

You contrast that with equity markets and the way we'd really characterize things is that it's a lot about more of the same. Everything that's worked for the last 10 years, people are still implementing those same strategies and same behaviors. That sets the scene, if you like, for a pretty sharp divergence in the views of those two markets. And a cynic would suggest it's unlikely both of them are going to be right.

… Since the start of the year, obviously things like artificial intelligence have infatuated people and provided another leg again to that tech dominance. That really, again, is re-emphasizing that more of the same type of argument where people are used to the success of these stocks, they keep on implementing those behaviors. I'd argue it's a little bit the same as real estate in Australia. People are so used to being on a good thing that they're really not giving up on those things lightly.

Morcos: We'll come back to that point a little later on because I've got some questions on that for you, Martin. But this concept of bifurcation and wealth inequality is a concept that you first raised during COVID. You touched on it in your most recent commentary. It seems to be a theme that you touch on quite often. Can you give us some insights into what you actually mean by that and what you're seeing in this reporting season in particular?

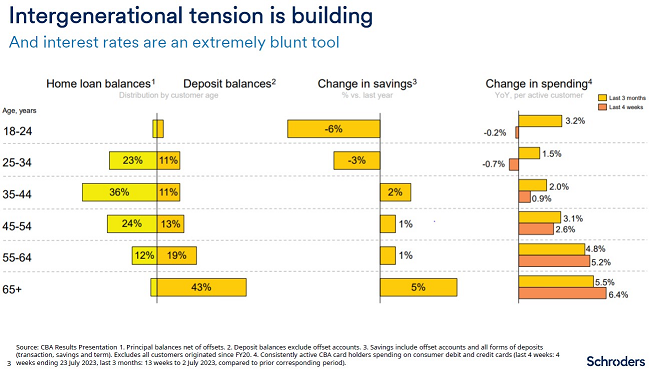

Conlon: Sure, Nat. I'll use this slide from CBA because I think it really encapsulated a lot of those underlying issues that the economies are facing.

It's not just the Australian economy, but the point you raised on bifurcation and what's happening with interest rates, the economy that we're facing today is arguably very different than times gone past. The reason I say that is, again, on this slide, that 10, 20 years of declining interest rates and booming asset prices have had a lot of impact on the economy in terms of wealth transfer. You can see on this slide that the home loan balances are owned by young people; the deposits are owned by old people.

So, what happens? When you put interest rates up, effectively what you're doing is transferring wealth from the young to the old. That's what interest rates do. People often forget that actually they don't create growth, they don't do anything, any of that stuff. What they do is transfer wealth within the economy. And with all the assets having been transferred to the old, to then put interest rates up and say to the youth of the economy that again, you've got to transfer more of your wealth to the elderly is really in our eyes increasing the tension. That increase in tension and income inequality and wealth inequality around the world is a massive issue, and we think it will be a big one for the next 10 years.

You're seeing it again on the right with the change in spending over recent months. What's happened? The younger cohorts have retraced their spending very significantly. At the older end, they're feeling better than ever. Actually, their spending is stable to increasing. So, that issue and the underlying impact of interest rates, I think is one that we've got to be very careful with. Also, it's why we really side with the RBA and say you've got to be careful how hard you push interest rates in this context because the economy you're facing is different, the impacts are pretty severe, and we're really only just starting to see the impacts of those interest rate rises now given fixed rate loans, et cetera.

Morcos: And beyond the housing sector, what else, what other patterns are you seeing in terms of consumer spending and the impact that these rising interest rates and inflation has had on consumer spending?

Conlon: Again, the obvious ones are nearly all results you saw those demographics coming through in the spending. So, depending on which cohorts you're facing, there were tougher times for some, and a lot of others were relatively unimpacted. So, interestingly, things like hardware stayed pretty buoyant. Again, they're really appealing to homeowners. Some of the older demographics, not so much to the younger ones. Travel, again, incredibly strong given that that tends to be disproportionately the older part of the community.

The other thing we'd point out and one of the things we found interesting in results season was Coles raised the fact that theft is going up a lot in supermarkets. So, you've had huge amounts of investment in front office or the technologies that we all see in terms of automated checkouts at the supermarkets. That's uncovering a whole other list of problems in terms of needing to combat theft. But again, the other thing that we took out of it was that a lot of those demographics most impacted by interest rates are really doing it pretty tough. You only resort to theft when you really have to and that says something about what interest rates are doing and perhaps some of the hidden and underlying effects that interest rates are having that really suggests that even though the overall economy we suggest is still really healthy, unemployment super low, most of the indicators really good, this is not a weak economy, certain cohorts are really doing it tough.

Morcos: Now, Martin, you talked about valuations in some of the areas, particularly in the tech stock has been somewhat crazy. We often consider ourselves thoughtfully contrarian. Can you share with us, I guess, your current views and whether you think things will change in that field?

Conlon: I'd probably have to summarize it as saying very little has changed so far. As I said at the outset, one thing that's obvious is that tech is going on with it. The dominance of technology companies around the world, they're still putting price up, the enthusiasm around cloud, et cetera is still providing enormous revenue strength for most of those companies. And because investors are so used to momentum paying off, they are very reluctant to leave behind those behaviors.

So, we're still seeing a situation where if you've got a good story, people can get excited about the growth runway over long periods of time. They are very reluctant to care much about valuation at all. They will pay extremely high prices. You saw that with Altium and so on in results here. Conversely, where there's any semblance of bad news, and that was the case with WiseTech Global and Iress, the price has suffered a little bit from downgrading those expectations. So, severe and arguably overreaction to a lot of short-term news, as is often the case in stock markets, but still a lot of enthusiasm with those infectious long-term good news stories.

Morcos: With China's economic slowdown, it's easy to be bearish on China, but does that also mean we're bearish on resources?

Conlon: China, I honestly find a fascinating economic story at the moment, because you're totally right to say it's not difficult at all to find bad news in China. I've got a few charts up here which really highlight how perilous the situation is in some areas.

You can see there that land sales volumes, the key property indicators in China have in general been decimated. Consumer confidence given obviously the severity of COVID lockdowns and the lack of largess that the Chinese citizens saw from their government relative to what we saw in the West, and very high and arguably destabilizing levels of youth unemployment. It's easy to look at that Chinese picture and say this looks awful.

Underneath that though, we think that the long-term picture is probably a little bit more nuanced in that their starting point is they've got plenty of housing. So, yes, property prices are going down. What they don't have, unlike Australia, is a housing shortage. They can supply property for most of their citizens. They've also spent enormous amounts on developing infrastructure over recent decades. So, the quality of their underlying infrastructure, it's modern, it's good.

So, the starting point is that they're facing a challenge stimulating the consumer. It's really in stark contrast to Western economies where we are super-reliant on services and consumption to fuel our economy. China is very much in a situation where their economy probably has the basis of good housing for all good infrastructure. They are really struggling, particularly in the face of an ageing population, to get those consumers to spend and to take the economy to the next level in terms of services.

But if I stand back from it, it's not really that clear to me that if you were to pick one as a starting point, that starting in the west with very services intensive economies, lots of debt, and very little in the way of goods manufacture, and in Australia, housing shortages, high immigration, a lot of tensions developing, that that's necessarily a much better starting point than where China is, where they're struggling to stimulate that consumer.

That's not exactly the picture you get when you look at the data and it's easy to be bearish on China. But we would suggest that actually the reason de-globalization is happening is that most Western economies are way too services sensitive and they're also too dependent on debt. In China, you've got very much the reverse situation where they're struggling with an ageing and declining population and perversely, they're losing most of their high-net-worth citizens to other countries. I always find it somewhat ironic that in Australia, we're sitting there trying to sell the benefits of becoming a larger country with lots of population growth. You go to most countries with a lot of people, what do they want to do? Leave. It is always ironic to me that companies and government are always preaching high immigration and the reason they do it is because it's easy growth for them. What we really should be worried about is GDP per capita, standards of living, productivity gain, some of those things that were raised in the Intergenerational Report recently and really are the secret to our living standards, not just growing the size of an economy.

This is an edited transcript of a webinar hosted by Schroders, a sponsor of Firstlinks. Part I features Natalie Morcos, Head of Product, Solutions, and Client Service, with Martin Conlon, Head of Australian Equities.

For more articles and papers from Schroders, click here.