In designing a system that will be robust in the face of social, economic or demographic changes, it is useful to note major trends that will affect Australians in retirement. A sound system will be dynamic and require change from time to time.

This paper notes seven currently identifiable trends.

1. The loss of long-term confidence and trust

The provision of retirement income through superannuation savings is a long-term venture over decades.

Unfortunately, the process and findings of the recent Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry have undermined long-term confidence and trust in institutions operating in the retirement income system.

The frequent changes to superannuation taxation and age pension structures and rules over the last 36 years have increased complexity and worked against providing confidence and trust to Australians to plan for their retirement.

This paper is advocating consideration of further changes, but as a move to improvement, we also advocate more stability and fewer changes in future.

2. Reducing home ownership

A system of integrated retirement provision needs to adapt to the changing pattern of home ownership.

There is an impending wave of retirees who will enter retirement as renters because home ownership has remained elusive. This higher proportion of renters is likely to persist across future generations unless housing affordability improves considerably. The needs of retirees who rent are very different from those who own a home given the vast difference in regular expenses on basic needs. Single pensioners who rent in the private market are poorly served by current arrangements. In fact, the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR) states 60-70% of older single people who rent private housing live in poverty.

Those retirees who own their home are in a more advantageous position than those in previous decades. Due to the long-term growth in property prices, the value of the home has far outgrown the value of many other assets. This provides a higher level of absolute wealth for retirees, but it is illiquid. This can be a dilemma for retirees, particularly those with limited other savings. Many may not wish to ‘right size’ to gain access to liquid savings because there is no suitable housing in their area.

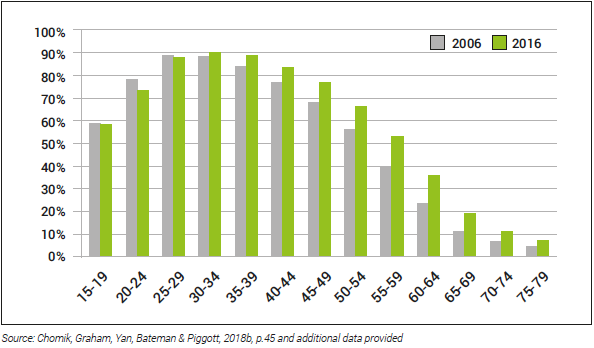

In addition, some will also need to consider possible reduction in age pension eligibility and other government support. Furthermore, those retirees who own their own home increasingly do so with a mortgage at the time of retirement. This proportion has been increasing over time, from 23% in 2006 to 36% in 2016 for those aged 60-64 years, and even higher rates for those in the younger age group, as shown in Graph 1.

Graph 1: A growing number of people have a mortgage on their home at the time of retirement

It seems reasonable to expect a growing number of Australian retirees will use part of their superannuation balances at retirement to pay off their mortgage. These trends will likely only reverse if there are significant changes to housing affordability. As a result, while superannuation will be an increasing proportion of people’s wealth in future cohorts, it is likely there will be a need in some households for it to serve purposes other than provide an income in retirement – it will also need to extinguish debts on retirement (or service them during retirement).

3. Growing dispersion in super and non-super wealth

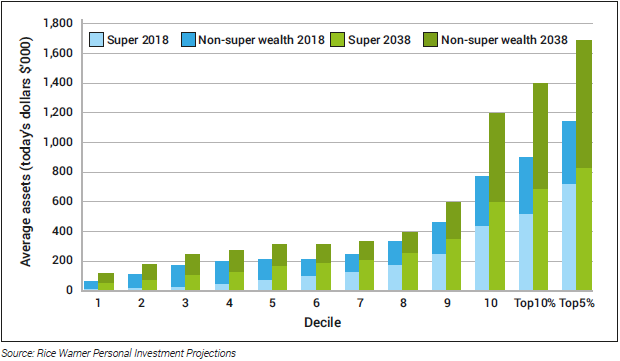

The highest income deciles in our society tend to hold much more in non-superannuation assets than the general population. Graph 2 demonstrates this distribution both today and in 20 years’ time based on projections from Rice Warner.

The results show that the top decile hold more than 2.5 times the fifth decile in non-super wealth today. This disparity is expected to increase to five times in 2038.

Overall wealth that includes superannuation savings will not see as large a growth in disparity, as those on middle incomes are largely expected to substitute some private savings/consumption for superannuation as the compulsory rate of superannuation contributions rises to 12%.

Most of this non-superannuation wealth is held either in investment properties or term deposits, so it will often provide regular income in retirement.

Graph 2: Distribution and composition of wealth by income decile

4. Changing life and health expectancy

Life expectancy, both as measured from birth and at retirement, has continued to improve. Therefore, the expected number of years retirees need to fund is growing. For those aged 60 to 90 years, mortality rates have been on a rapidly-improving trend since the 1970s (i.e. death rates have decreased) due to medical advances. That said, mortality rates for those aged 90 years and over have deteriorated (death rates have increased). The Australian Government Actuary has noted the improvements in mortality for 60-90-year ages have led to an increasing proportion of the population living to the older years which may have contributed to the decline in average health of the older age group.

The healthy life expectancy (that is the years lived free of a disability or a severe or profound core activity limitation) has also been increasing. The effect is that a greater proportion of the population should expect to live well into their mid to late 80s or beyond.

However, there is also evidence in several developed economies that the increased life expectancy may have slowed or even stalled. This result may be caused by several reasons, including an increasing difference in life expectancy between different socio-economic classes.

A natural consequence of a growing dispersion in wealth is a growing diversity in health outcomes, including for life expectancies.

5. Growing health and aged care costs

An integrated system needs to cater for the likely significant growth in health and aged care costs. These costs are growing in real terms (i.e. faster than inflation and conservative investment returns) because of higher standards of care (increasing per unit cost) and the larger number of older people from increased life expectancy and the baby-boomer generation. CEPAR reports estimate that public spending on aged care will rise from 1% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to over 2% by 2050.

Longer term projections show aged care is the second fastest growth category of expenditure (behind the National Disability Insurance Scheme). For aged care, the Commonwealth government meets around three-quarters of total costs and individuals meet less than one-quarter. Furthermore, aged care providers may ask for (but no longer demand) significant lump sum payments by individuals if residential care is required. Meeting these costs may require release of equity from the family home.

Given life expectancy improvements, the lifetime risk of needing to enter permanent residential aged care is increasing. Most recently (in 2014), for a person aged 65 this risk has been estimated at 42.8% for men and 59.3% for women (up from 33.5% and 53.8% respectively in 2000). These percentages are likely to increase with ongoing mortality improvements.

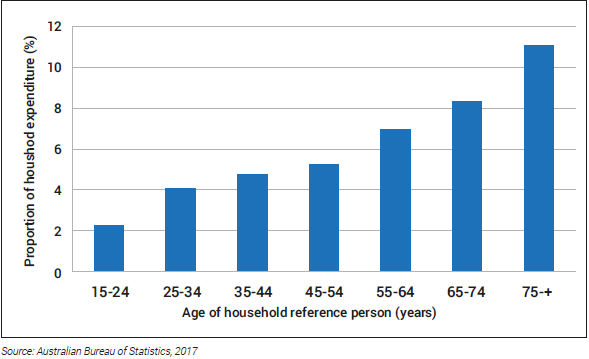

For medical and health care costs, government meets nearly 70% of total costs across the whole population, health insurers meet nearly 10% of total costs, and individuals (net of private health insurance refunds) meet nearly 20% of total costs. Significantly, the proportion of household expenditure net of any government rebates or health insurance refunds, steadily increases on these items with age (Graph 3).

Graph 3: Proportion of household expenditure on medical and health care

6. Changing work patterns

Work patterns, which have become more variable, also need to be supported by an integrated system of retirement provision. Women have increased their participation in the workforce at all ages, including returning to work after having children. Part-time employment across the whole population has doubled from 16% of the workforce to 32% over the last 40 years [Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019a]. Potentially, if the ‘gig economy’ continues to grow, this development will further contribute to greater variability of work patterns and lower superannuation contributions for many gig workers. Job security also appears to have reduced for both full and part-time workers in the past ten years.

Many older workers are increasingly choosing to work longer with transition to retirement by engaging in part-time work. Australia’s part-time employment share of over-55s has more than tripled from just under 10% to 34% over the last 40 years.

Greater variability in work, and therefore income, affects people’s capacity to accumulate savings for retirement and how they begin the pension phase if they choose to transition to retirement by working part-time. In the case of those transitioning to retirement, they also need to navigate the interaction of superannuation and Age Pension systems.

7. Decreasing age pension dependency

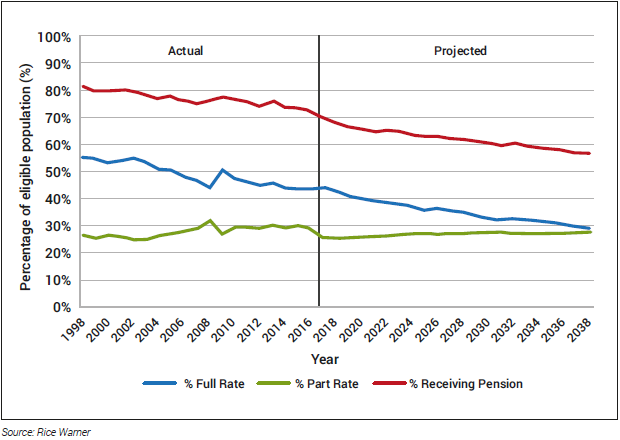

Over coming decades, a smaller proportion of the aged population is expected to receive the age pension as income support. Through a combination of the maturing superannuation system (with people accumulating more superannuation assets over their life), the transition to an increasing age pension eligibility age and recent changes to age pension means tests, the projected proportion of the eligible population receiving the age pension will fall.

Graph 4 shows the proportion receiving a full age pension has reduced significantly over the last 20 years. The number of retirees not receiving any pension has also grown.

Graph 4: Proportion of the eligible population receiving the Age Pension

It also shows that the proportion of the eligible population receiving the age pension is projected to continue to fall from around 68% in 2018 to around 57% in 2038 assuming the SG increases to 12% as legislated. This fall is comprised of a significant fall in the proportion of the eligible population receiving the full rate of age pension (from 42% in 2018 to 29% in 2038) and a relatively smaller increase in the proportion of the population receiving a part-rate Age Pension (from around 25% in 2018 to 28% in 2038).

Retirement planning is essential

One consequence of these trends is that more retirees will face greater complexity in retirement planning because they will be subject to the complex means tests. Another consequence is more retirees may therefore be very deliberate in how they structure their financial affairs to ensure they maximise their age pension entitlement, because the opportunity cost of not doing so is potentially high.

For a full copy of the Actuaries Institute's 'Options for an Improved and Integrated System of Retirement', Green Paper, August 2019, click here.

The article above is an extract from Section 3, written by Anthony Asher (University of NSW), David Knox (Mercer) and Michael Rice (Rice Warner). It draws on three papers presented at the Actuaries Financial Services Forum in May 2018, namely:

- The Age Pension means test: contorting Australian retirement (Dr Anthony Asher & John De Ravin)

- Retirement Incomes – Australia vs the Rest of the World (Dr David Knox)

- The Age Pension in the 21st Century (Michael Rice)