Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), the 100-pound gorillas of the investment world, are pulling away from real estate and infrastructure and deploying more capital into listed deals and technology.

(An accepted definition of an SWF is a special-purpose investment fund owned by the general government for macroeconomic purposes. They manage assets to achieve financial objectives using a set of investment strategies. The definition excludes foreign currency reserves held by central banks and state-owned enterprises, government-employee pension funds and assets managed for the benefit of individuals).

Changes in SWF asset allocation

Using a three-year database of investments by more than 60 SWFs, the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds and Bocconi University recently released a report (‘Dealing with Disruption’, issued 16 July 2018) that found that the number of private deals dropped from 196 in 2016 to 184 in 2017, while the number of listed investments rose from 94 to 119.

SWFs have long been active participants in private markets. Their scale, long-term investment horizon and little need for liquidity was seen as a good match to private market investments such as real estate and infrastructure.

But as the Report points out, SWFs appear to be facing challenges deploying capital. Abundant liquidity and strong competition for high quality assets from a growing array of institutional investors looking for real estate and infrastructure assets is pushing valuations higher.

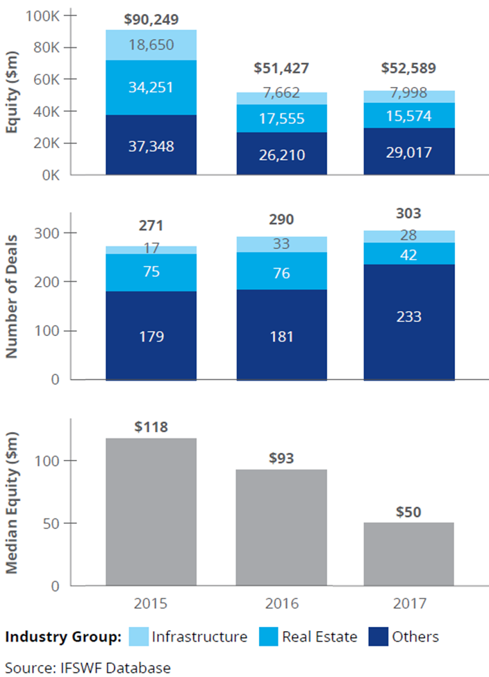

In 2017, the number of direct real estate and infrastructure investments made by SWF’s declined from a total $25.2 billion in 2016, split between 76 deals in real estate, and 33 in infrastructure, to $23.6 billion, comprising only 42 deals in real estate and 28 in infrastructure (Figure 1).

In the real estate sector, there was almost a 40% decrease in the number of SWF investments in private markets between 2016 and 2017, while in infrastructure, the number of deals fell by 15%.

Figure 1: SWF Direct Investments in Real Estate and Infrastructure vs Total

Global protectionism encourages investment in other places

In infrastructure, rising global protectionism also threatens to stymie foreign direct investment by SWFs in strategic sectors. The Report acknowledges SWFs:

“… are encountering greater resistance from regulators, preventing them from investing in major infrastructure assets. Regulatory regimes in the US and Europe are installing more stringent screening processes for foreign direct investments in strategic infrastructure assets.”

Asia and Latin America are now on the radar for SWFs looking for established infrastructure companies with predictable cash flows. In 2017, SWFs completed 17 direct investments in emerging-market infrastructure, of which 10 were cross-border, for a total value of $3.8 billion versus 11 deals in developed markets totalling $4.2 billion.

The Report noted that:

“… while it might, on the face of it, appear to be a higher-risk strategy, emerging markets can carry lower potential political risks as there are fewer concerns about foreign investment in infrastructure and SWFs can pair with a domestic promotor. Deals are often less complex, with fewer parties involved, and lower costs reducing third-party operating risk.”

Across their direct investment platform, the median equity investment by SWFs was $50 million, just over half the $90 million recorded in 2016. Excluding real assets, such as real estate and infrastructure projects, this trend was even more marked. The median equity investment was $27 million, plummeting from that of previous years: $60 million in 2016 and $58 million in 2015.

Increasing sophistication of SWFs

While there are certainly headwinds in private markets, SWFs have been taking advantage of the weak US dollar, strong global growth, and expectations that tax reform in the US would push stock markets to record highs, and increasing their direct investments into listed companies. In 2017, SWFs bought publicly listed shares in 119 transactions – 39% of the total – up from 94 deals in 2016, which represented 32% of the total.

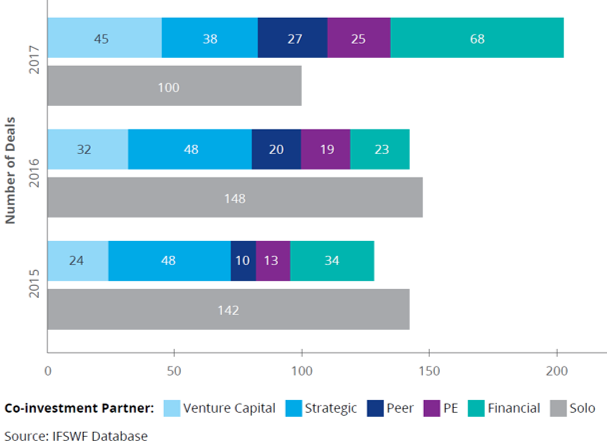

With the growing size and sophistication of SWFs, they are now less likely to be simple investors in funds. They are increasingly collaborating with other investors, including their peers and private equity firms on investments, enabling them to harness external expertise across sectors. In an era where generating above-market returns requires a much more active management of investments,

“SWFs are now genuinely participating in, and setting the strategic agenda of, their portfolio companies, using their global influence to drive investment performance and working actively with (and learning from) more experienced joint-sponsors and partners in a deal.”

In 2017, the trend reached a new high as SWFs completed 203 investments in a consortium or partnership, more than double the number of solo deals (Figure 2).

Figure 2: SWF Direct Investments – Partnerships and Consortia

SWFs are also investing more in technology and particularly earlier stages of the private equity cycle. There was a material uplift in investments in innovative sectors in 2017, with 29 deals in technology and 16 in healthcare, up from 15 and 6 respectively in 2016. The breadth of disruptive technology stretches from augmented reality and artificial intelligence to new materials, biotechnology, innovative pharmaceuticals and new medical devices.

SWFs continue to grow their asset base, up 13% in the year to March 2018 to US$7.45 trillion, as reported in the 2018 Preqin Sovereign Wealth Fund Review. With that amount of firepower, any changes in how and where they deploy their capital will have implications for global financial markets and all investors.

Adrian Harrington is Head of Funds Management at Folkestone, a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This article is in the nature of general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

For more articles and papers from Folkestone, please click here.