The Callaghan Report prepared for the Treasury on Australian superannuation released four years ago was the first to highlight that people are just not spending their superannuation (super) balances. This finding was confirmed in a recent report released by the Grattan Institute which suggested that guiding people towards purchasing lifetime annuities as the major solution to this perceived problem.

The issue I raise here is to question whether people not spending their super is a problem at all but rather a signal of more fundamental failings in our retirement income system. The purpose of investing is not for people to simply accumulate wealth but rather to assist them to achieve their optimal pattern of consumption over their life. At certain times in their life people will earn more than they want to spend on consumption, and they will build up savings. At other times, they will want to spend more on consumption that their earnings permits and so they have to draw down their savings and/or go into debt. The whole purpose of our mandatory superannuation system is to ensure that people do not consume too much during their working life and so not be able to fund their consumption in retirement. Hence, superannuation has an important role to play in our retirement system to assist people in achieving their optimal pattern of consumption over their life.

In this setting, mandatory super is quite paternal as it is saying to people that without our intervention you will overspend during your working life, and we are going to make it more difficult for you to do this. Now we are being told in the latter years of their lifecycle that they are not spending sufficiently, and we need to take steps to ensure that you will spend more. The Grattan Report suggests that it is concern for longevity and investment risk that is the main inhibitor to people not spending their superannuation balances. Their solution is to guide people to invest the majority of their balances in lifelong annuities. This will certainly solve the perceived problem of getting rid of the super balances as the annuity will be worthless upon the person’s death. There are a number of reasons why people need forcing to take on lifetime annuities with a major one being that dying ‘early’ leaves the issuer of the annuity with so much of a person’s hard-earned cash.

The fact is that we have a system which forces people to save (and so forego consumption) during their working life and now we are proposing a system which encourages them to purchase a lifetime annuity and so fully consume the funds they accumulate over their working life. This is completing the cycle as we are saying that people left to their own devices will make the wrong consumption choices not only while they are working but also during their retirement.

Are mandatory super contribution rates too high?

This is all well and good, but what is disappointing is the Grattan report bases its recommendations on circumstantial evidence without ever addressing the issue as to what are the consumption needs of retirees. This is relatively easily done by modelling the consumption of an individual over their lifecycle incorporating all relevant aspects of the environment (e.g., earnings, investments, super, welfare benefits, longevity and so on). What the report fails to give serious consideration to is that people just do not spend all of their retirement savings because they just do not feel the need to do so. To gain greater insights into this, we need go back several years to when the mandatory contribution rate stalled at 9.5%. At that time there was much discussion of the need to further increase the contribution rate and three independent studies were conducted to throw light on this question. The three studies (one from the Grattan Institute, one from ANU and one that I conducted at UTS) all found grounds to suggest that at 9.5%, the contribution rate was already too high for vast sections of the population. By too high, I mean that mandatory super was already forcing people to give up too much consumption during their working life and resulting in them accumulating more savings than what they require to fund their consumption in retirement. The implication being that mandatory super causes them to enjoy a more modest lifestyle while working and they simply do not want to drastically change that lifestyle when able to in retirement resulting in them leaving relatively large estates. If we see people not spending their super balances, the first reaction should not be how can we make them spend it but rather to examine our retirement income system to determine whether the mandatory contributions rates are being set at too high a level.

One of the mistakes that we consistently make when talking about super is to assume it is costless and so the more we have the better. This is blatantly wrong as super comes at the cost of consumption foregone during one's working life. Hence it is wrong to segment a person’s life and look at optimal behaviour over just one phase of that life. This is just the mistake the Grattan Report makes here by suggesting that we have this pile of money, and we must spend it rather that considering the question as to whether we needed to accumulate this pile in the first place.

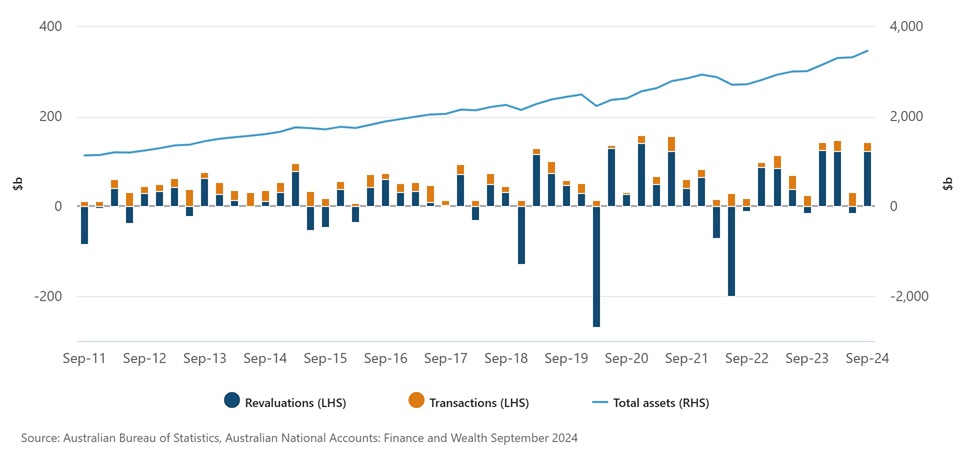

Superannuation funds’ financial assets

Another mistake we make when talking about super is to assume that it impacts on all people equally and so we can set one policy that is optimal for all. For as much as half the population, a 12% contribution rate is clearly causing them to tighten their belts and spend less than they would like over a considerable proportion of their working lives. Further, it is almost certainly preventing them from ever purchasing a property as we see in the diminishing levels of home ownership. In other words, they are conditioned to being used to a lesser lifestyle which they do not want to drastically change when they get the pot of gold at retirement. Indeed, it is not surprising that they choose to devote much of this pot of gold to assisting their children in what are increasingly more difficult times rather than spend it themselves or donate it to the issuer of a lifetime annuity. For the wealthy (say top 25%), we have a completely different situation in that the pile of gold on retirement reflects not only the accumulation of significant mandatory contributions, but also a huge amount of voluntary contributions attracted by the tax incentives provided to invest via super. These people are never going to spend their accumulated balances and quite sensibly leave these funds in tax-shielded super almost up to when they pass them on as part of exceptionally large estates.

Our retirement income system needs revamping

The Grattan Report does have some good recommendations (e.g., the government to offer a lifetime annuity) but to a large extent it is concentrating on an illusory problem. In previous studies, they and others have established that our current retirement income policy is more than adequate to fund the retirement of the vast majority of the population. The real problem is not that we need retirees to spend their pile of gold but rather that we have a retirement income system that we have allowed to grow without any serious attempt to see whether it is working to the lifetime benefit of all constituents of the population. The ‘so what’ of seeing that people are sitting on their super balances is not to plug another hole in the retirement income system but rather to conduct the long overdue comprehensive analysis of the whole retirement income system to see if we have even the most basic of settings right.

Emeritus Professor Ron Bird (ANU) is a finance and economics academic and former fund manager.