There are a few key questions that people need to think about when planning for their retirement, such as:

- How much do I need (and can afford) to save for my retirement?

- How do I invest my superannuation to improve my retirement outcome?

- How do I safely draw down and spend my savings during retirement?

As compulsory Superannuation Guarantee (SG) contributions only commenced in Australia in 1992, starting at 3% of earnings and gradually increasing to 9% by 2002, it is fair to say that our superannuation system is still relatively immature. In addition, the SG only applies to employees who earn more than $450 in a calendar month and doesn’t apply at all to the self-employed and contractors in the so-called ‘gig economy’.

Large super balances are relatively new

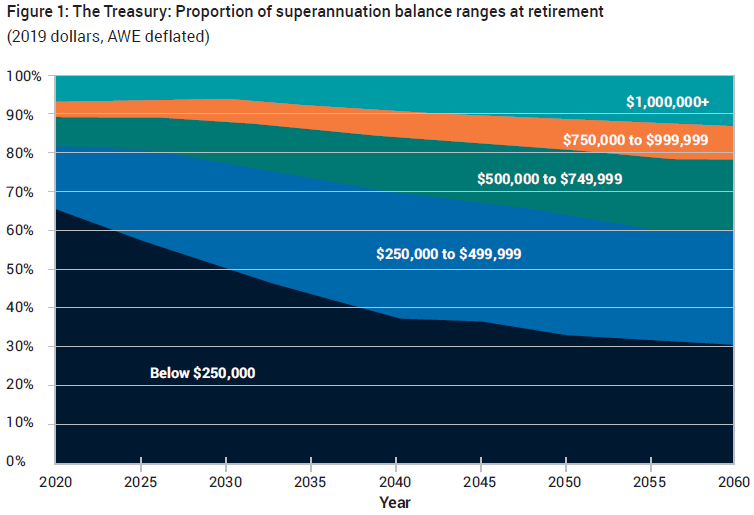

Thus, it is only recently that a significant number of Australians began retiring with material amounts of retirement savings, with around 35% of superannuation balances at retirement reaching $250,000 or more.

Over the next 40 years, this proportion is expected to double, with around 70% of superannuation balances at retirement in 2060 expected to reach $250,000 or more (in today’s dollars). Indeed, by then, around 40% of superannuation balances at retirement are expected to reach $500,000 or more (in today’s dollars).

Retiree confidence to draw down more

There have been numerous studies, including one by CSIRO-Monash Superannuation Research Cluster, which indicate that most retirees in their 60s and 70s draw down on their account based pension (ABP) at modest rates, close to the minimum amount each year (which is 5% of their account balance for those aged 65 to 74). This behaviour will result in them living an unnecessarily modest retirement, many behaving as if they are in poverty.

There have been many reasons proposed for why retirees behave this way, among them a fear of running out of money and uncertainty about how long they will live. Some might also want to leave the home as a bequest, so they don’t consider using the equity in their residence. Hence, they try to manage their own longevity risk by spending cautiously.

Since the early 1970s, the life expectancy of the average 65-year-old has increased from about 12-13 years to 20 years for men and 22 years for women. But longevity is not uniform, it varies considerably from person to person, so some form of longevity protection will be helpful for many Australians.

A retiree’s draw down and spending strategy is also driven by how much savings they have and how the assets test affects their eligibility for the age pension.

When is age pension eligibility lost?

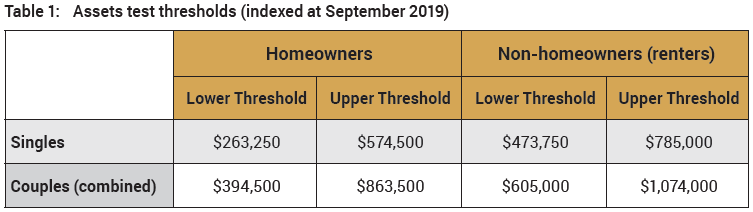

The relevant assets test thresholds are set out in Table 1, with a full age pension applying below the lower thresholds and gradually reducing to zero when the value of assessable assets exceeds the upper thresholds (noting that some assets are excluded from the assets test, such as a person’s main residence).

If a retiree has less than $300,000, then they will be entitled to a full age pension for most (if not all) of their retirement and it will be their major source of income. In this situation, their superannuation savings will supplement their income and the age pension provides a good income base as well as adequate longevity protection in most cases.

On the other hand, if a retiree has more than $800,000 then they are also likely to be homeowners and, after taking into account other non-superannuation assets, are less likely to be eligible for much, if any, age pension during their retirement. In this situation, their superannuation is predominantly a substitute for the age pension and, in addition, they often have the capacity to not have to draw down as much of the capital component of their savings.

The age pension is likely to provide enough certain lifetime income for low balance members, and high balance members won’t necessarily need to draw on as much of their capital anyway. But the high proportion of Australians in the middle (with superannuation balances between say $300,000 and $800,000) could benefit greatly from more certainty for more of their retirement income.

This ‘middle’ group will be eligible for a part-age pension for a substantial portion of their retirement and, as a result, the means test rules will be an important consideration for them.

For this middle group, it is therefore worth noting that legislation was passed in February 2019 to amend the means test rules that apply to longevity protection products with effect from 1 July 2019. Under the new rules, only 60% of the purchase amount of a lifetime income stream will be an assessable asset and only 60% of the payments will be income for the means tests.

These regulatory changes should, in time, promote the development of new longevity protection products such as deferred lifetime annuities (DLAs) or deferred group self-annuitisation (GSA) products which should help retirees plan their retirement spending with more confidence.

What is the ‘taper rate’ and when did it change?

The taper rate is another important part of the assets test used to determine eligibility for the age pension. Since 1 January 2017, a retiree’s annual pension is reduced by $78 for each $1,000 of assets above the relevant lower thresholds (as set out in Table 1). Before 2017, the taper rate was half that amount, at $39.

At the time of the change to the taper rate in 2017, the lower thresholds were increased by more than 30% which, according to the government meant that more than 50,000 part-pensioners became eligible for a full pension for the first time. As the SG system matures, more people are expected to retire with higher superannuation balances and as a result of this change are expected to lose more of the age pension.

How does the taper rate impact retirees?

To understand its impact, let’s look at some cameos for a worker on average annual earnings of $90,000 and compare the results for a superannuation contribution rate of 9.5% versus 12% (i.e. an additional 2.5%) paid over 40 years to age 67. Based on a marginal tax rate of 32.5%, if fully offset or sacrificed, the person’s net take home pay would reduce by about $61,000 over the 40 years.

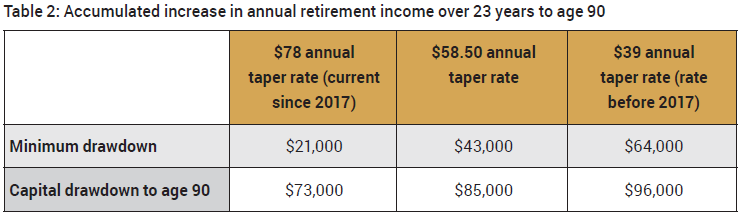

Following retirement at age 67, if the retiree is a single non-homeowner and draws down the minimum amount over 23 years to age 90, then the increased income produced by the additional savings is partially offset by a reduction in the age pension as set out in Table 2.

On the other hand, if the retiree gradually draws down all their capital over the 23 years to age 90, they not only gain the benefit of spending more of their savings, but they also become eligible for higher age pension payments sooner. Note that the ‘minimum drawdown’ scenario ignores any residual payments to beneficiaries and focuses on spending in retirement.

As Table 2 shows, if the retiree draws down and spends the minimum amount each year, the annual taper rate would need to be close to $39 for the retiree to receive total additional retirement payments higher than the accumulated reduction in the person’s net take home pay of $61,000.

Based on the current taper rate of $78, the retiree is caught in a ‘trap’ whereby their total additional retirement payments over the 23 years to age 90 (i.e. $21,000) are $40,000 lower than the accumulated reduction in the person’s net take home pay to fund their higher retirement savings.

The retiree would be in fact be better off under a $78 annual taper rate if they also gradually draw down and spend all their capital by age 90. In this scenario, the retiree’s overall net benefit would further improve with the lower taper rates.

A higher taper rate does encourage retirees to spend their savings as quickly as possible until they become eligible for the full age pension, but there is little evidence that this occurs in practice.

The confidence to spend

One of the problems facing retirees is the complexity around the means test. We need to find a way to deliver appropriate advice cost-effectively to help the growing number of people entering retirement with sufficient superannuation savings to encounter these problems. In particular, the ‘middle’ group identified earlier, who will be eligible for a part-age pension for a substantial portion of their retirement, need this guidance the most.

If one of the objectives of the superannuation system is to 'facilitate consumption smoothing over the course of an individual’s life', then this ‘middle’ group would benefit from:

- encouragement to acquire longevity protection to give them more confidence to spend their savings during retirement

- a fairer taper rate that does not unduly encourage them to spend their retirement savings too quickly, and

- low cost access to information, guidance and advice to help them make better decisions about their retirement.

Given the interconnectedness of the system, it is important that all the relevant levers are considered in conjunction with each other, including how it impacts on the efficiency and effectiveness of any other changes such as increasing the SG to 12%.

Andrew Boal is the CEO of Rice Warner. He specialises in providing actuarial and strategic consulting advice to leading companies and superannuation funds. This article is general information and readers should seek their own professional advice. It is an extract from the Actuaries Institute Dialogue Paper called 'Spending in Retirement'. A full copy of this paper can be found here.