A common perception in finance is that the risk in growth assets, like equities, declines over a longer investment horizon. Recent research by consulting economists, Drew, Walk & Co into the equity risk premium (ERP) shows that even over the long run, equity investing is like a chocolate wheel: there are plenty of winners, but also losers. Retirees should not assume that the volatility of equity returns will be smoothed out over time, not even over 20 years. Retirees need to factor this into their goals for retirement income.

What is the ERP?

The ERP is the additional return that investors require, on average, for taking the extra risk of investing in equities, over and above any risk-free return (the government bond return). If investors do not expect to receive this additional return, they won’t invest in the risky asset.

The ERP has been labelled the most important variable in finance and is used in a number of applications. Just about every decision in finance has a link to the ERP.

Unlike a long-term bond, where an investor can hold to maturity and receive a known term premium, the equity premium is unknown in advance and is far from certain. The challenge for investors and superannuation fund members is the range of actual equity return outcomes, compared to the originally expected ERP.

The (un)predictable equity risk premium

In their paper, Drew, Walk & Co explore whether investing in equities in previous 20-year periods was adequately rewarded for the risk taken. They calculated the historical equity return (out)performance over various periods in a range of jurisdictions. The report concludes, among other things, that the equity return (out)performance:

- is uncertain, and its timing and magnitude are unpredictable

- has shrunk in recent history to below its long term average in Australia

- was only 1% per annum for the last 20 years.

The flaw of averages

Traditionally, the ERP is calculated by averaging the entire period of available historical data, and this average is then used to make an assessment of future returns. In using such an average, people miss the fact that an Australian retiree household is planning for roughly 30 years, which is obviously well short of the 115 years since 1900.

Long-run historical average returns can be flawed because:

- They are not an indicator of future outcomes.

- There are potential survivorship biases, where losses incurred in failed companies are not properly included.

- The early history reflects the benefit of Australia emerging as a financial economy. Since WWII, Australian equities have actually performed lower than prior decades and in line with other major global markets.

- Most people do not get the average outcome. Around 50% will do better and a similar proportion will do worse.

In addition, retirement is different, because most retirees:

- Need to spend their capital and so are impacted by sequencing risk.

- Segment their retirement capital over a range of time horizons within their retirement timeframe, to meet their investing and spending goals.

- Won’t have an unbroken exposure to equities for decades.

Time doesn’t diversify equity risk

Most people assume that 20 years is long enough to get the ‘long-run average’, however the research indicates that there are a wide range of potential outcomes, even when they can stay invested for 20 years.

Only with hindsight, at the end of the 20 years, will a retiree find out their premium (if any) for taking equity risk over that period.

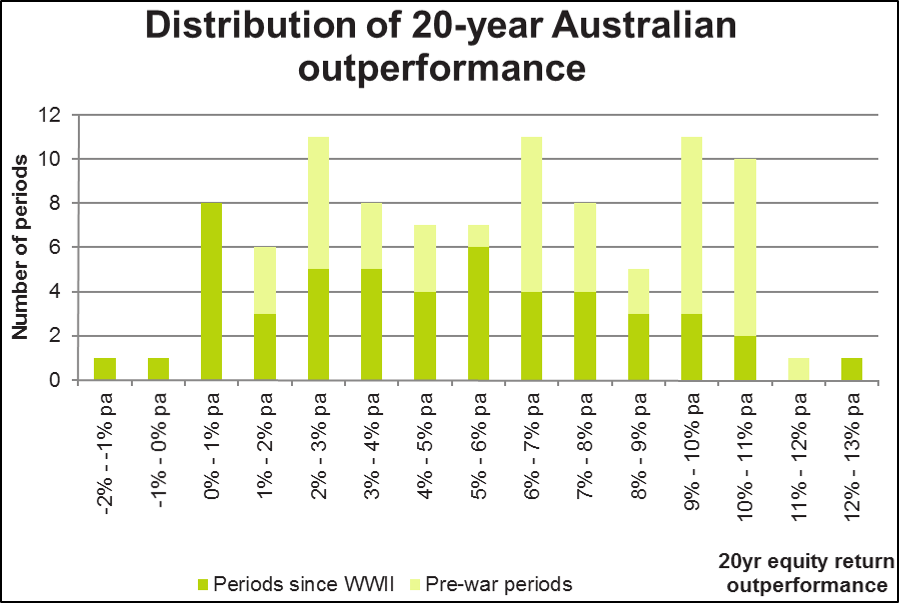

Figure 1 shows the frequency of the 20-year historical equity return (out)performance. The graph shows that Australia performed better in the first half of the 20th century, when it would still have been an emerging economy rather than the fully developed market economy it is today. There have been 14 periods of 20 years in Australia where the equity return outperformance exceeded 10% per annum, but they were mostly before WWII (shown in light green).

Figure 1: Distribution of 20-year Australian outperformance

The typical retiree needs some equity exposure

Even though equity investing is volatile over the long range, most retirees typically have the time horizon and risk tolerance to invest in at least some equities and they are likely to benefit from the premium. This is why the great majority of account-based pensions already have a generous exposure to equities.

A retirement risk management strategy

But what do retirees do about the equity risk? What happens when something goes wrong? Instead of adopting a conventional ‘set and forget’ approach, well-advised retirees work with a risk management strategy for their equity exposure in retirement. The idea of having a safety strategy is common in everyday life, and when it comes to investing in risky assets, retirees should be no different.

Using a long-term bucket for equities in retirement is one strategy that is sometimes used. However, as equity outperformance is uncertain over 20 years, a retiree will not have certainty about how much will be in the bucket after even as long as 20 years.

Portfolio allocation in retirement

Starting with Chhabra (one of the early papers that advocated goals-based investing rather than efficient frontier targeting), there has been a distinctly different approach for making asset allocation decisions in retirement. This approach is to consider the full range of the retiree’s objectives and goals. Instead of trying to meet all targets with one investment decision, a goals-based approach will segment the main objectives. The approach is similar to the asset-liability matching practised by many insurance companies and defined benefit funds around the world.

Matching objectives enables a retiree (or their adviser) to consider the risk/reward trade-off that is represented by the ERP and select a suitable allocation of risk for each objective. For example:

- Generating income for life to meet essential spending needs will generally have a limited exposure to risky assets, as the objective is to maintain a minimum standard of living for life.

- Investing for spending on holidays and luxuries later in retirement can have a higher allocation to growth assets.

Under this approach, retirees with differing objectives, but the same wealth, age and risk tolerance will actually have different asset allocations.

Spinning the chocolate wheel in retirement

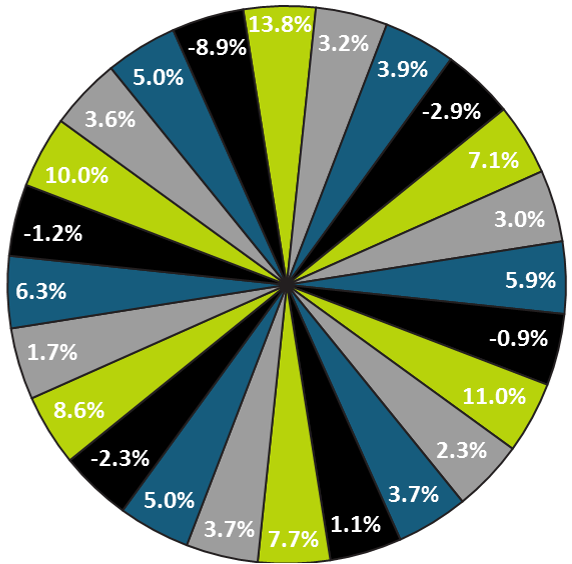

Retirees should think about investing as being like spinning the chocolate wheel shown. This has been assembled using the global historical numbers, the average of which roughly matches the forward projections for the ERP made by Drew, Walk & Co. in their paper.

Figure 2: Chocolate wheel of global historical average annual equity return outperformance over-20 year periods

This ‘chocolate wheel’ reminds retirees that the average annual outperformance that might be expected over a 20-year investment period is not certain. It will not be a guaranteed rate. Most outcomes are attractive returns, but the risks are broader than what Australian history alone suggests.

Conclusion

For investors and retirees today, care needs to be taken drawing conclusions from long-term averages when planning for the future. In addition, a set and forget approach will not ensure that a retiree’s exposure to equities risk will be appropriately mitigated.

Jeremy Cooper is Chairman of Retirement Incomes at Challenger, and chaired the Super System Review (the ‘Cooper Review’).