These days, we take for granted that the value of the Australian dollar fluctuates against other currencies, changing thousands of times a day and at times jumping or falling quite a lot in the space of a week.

But for most of Australia’s history, the value of the Australian dollar – and the earlier Australian pound – was ‘pegged’ to either gold, pound sterling, the US dollar or to a value of a basket of currencies.

The momentous decision to float the dollar was taken on Friday December 9 1983 by the Hawke Labor Government, which was elected nine months earlier.

As they approached the cabinet room at what is now Old Parliament House, Treasurer Paul Keating asked Reserve Bank Governor Bob Johnston to write him a letter to say the bank recommended floating.

The letter, dated December 9, referred to the bank’s concern about the “volume of foreign exchange purchases and its belief that if these flows are to be brought under control we shall need to face up without delay either to less Reserve Bank participation in the exchange market or capital controls”.

By “less Reserve Bank participation”, Johnston meant a managed float. Direct controls were to be considered “as a last resort”.

The bank had long maintained a 'war book', bearing the intriguing label 'Secret Matter', outlining the procedures to be followed in the event of a decision to float.

An updated version was handed to the treasurer the day before the decision.

The US and the UK floated their currencies in the early 1970s. Since the early 1980s the value of the dollar had been set via a 'crawling peg' – meaning its value was pegged to other currencies each week, and later each day, by a committee of officials who announced the values at 9.30 each morning.

If too much or too little money came into the country as a result of the rate the authorities had set, they adjusted it the next day, sometimes losing money to speculators who had bet they wouldn’t be able to hold the rate they had set.

Keating had Johnston accompany him to the December 9 press conference instead of Treasury Secretary John Stone, who had argued against the float in the cabinet room, putting the case for direct controls on capital inflows instead.

Johnston’s presence was meant to make clear that at least the central bank supported floating the dollar.

Speculators now speculate against themselves

Keating told the press conference the float meant the speculators would be “speculating against themselves”, rather than against the authorities.

One banker quoted that night confessed to being “absolutely staggered”. “I’m not sure they know what they have done,” the banker said.

The following Monday on ABC’s AM program, presenter Red Harrison heralded “a brave new world for the Australian dollar”. He said, “from today the dollar must take its chance, subject to the supply and demand of the international marketplace, and there are suggestions that foreign exchange dealers expect a nervous start to trading when the first quotes are posted this morning”.

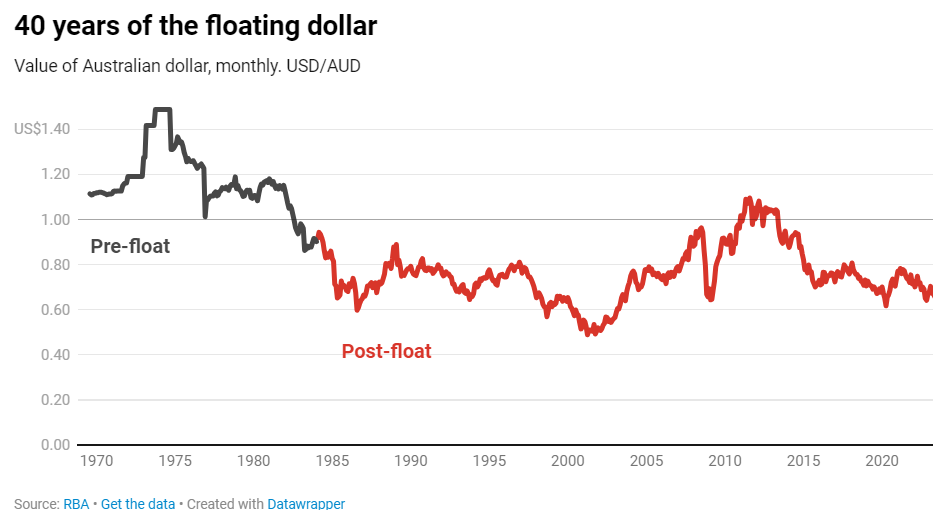

At the time, the Australian dollar was worth 90 US cents. At first it rose, before settling back.

Since then, the Australian dollar has fluctuated from a low of 47.75 US cents in April 2001 to a high of US$1.10 in July 2011.

The long road to the float

The idea first took hold in Australia when Commonwealth Bank Governor “Nugget” Coombs visited Canada in 1953, at a time when it was one of the few countries with a floating exchange rate.

On his return, Coombs wrote the bank should consider Canada’s experience.

A strong advocate from the mid-1960s was the bank’s economist Austin Holmes. Among those he mentored at what by then was called the Reserve Bank were Bob Johnston, Don Sanders, and John Phillips.

All three were in the cabinet room when the decision was taken.

Backed by Cairns, opposed by Abbott

An unlikely advocate in the 1970s was the left-wing Labor Treasurer Jim Cairns.

But asked in 1979 whether he was in favour of a float, the then Reserve Bank governor Harry Knight responded by quoting Saint Augustine, saying “God make me pure, but not yet”. An oil shock was making markets turbulent at the time.

In 1981, the Campbell inquiry into the Australian financial system delivered a landmark report to Treasurer John Howard, recommending a float. The idea was backed by neither the Treasury nor Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser.

Two years later, Howard watched from Opposition as Labor did what he could not.

The Liberal Party generally backed Labor’s move, with one notable exception – the later Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, who in 1994 wrote that, “changing the price of the dollar moment by moment in response to each transaction makes no more sense than altering the price of cornflakes every time a buyer takes a packet off the supermarket shelves”.

A success by any measure

The floating exchange rate has served Australia well.

When the Australian economy has slowed or contracted – in the early 1990s, the Asian financial crisis, the global financial crisis and in the COVID recession – the Australian dollar has fallen, making Australian exports cheaper in foreign markets.

When mining booms have sucked money into the country, the Australian dollar has climbed, spreading the benefit and fighting inflation by increasing the buying power of Australian dollars.

It’s why these days, hardly anyone wants to return to a pegged rate.

Selwyn Cornish is Honorary Associate Professor, Research School of Economics, Australian National University. John Hawkins is Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.