The last five years have been very eventful for bank shareholders, with each year bringing a new set of worries predicted to bring the banks (and their share prices) to their knees.

2020 brought capital raisings from NAB, and Westpac missing its first dividend since the banking crisis of 1893 as experts forecast a 30% decline in house prices and 12% unemployment. Then 2021 saw the banks grappling with zero interest rates. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) warned management teams about the systems issues they may face from zero or negative market interest rates, an issue that seems quite comical now.

In 2022, the RBA raised the cash rate from 0.10% to 3.10%, its most rapid tightening ever. And in 2023, the concerns switched to the impact of sharply rising interest rates on bad debts and the ‘fixed rate cliff’. Ultimately we saw little impact on earnings as borrowers made lifestyle changes to maintain mortgage payments.

As the banks coped with the above issues, the reason touted for selling bank shares switched to valuations in 2024 and 2025, with analysts advocating investors to sell all their banks as they were simply "too expensive". However, this call seemed premature, with the banks rallying +33% throughout 2024. Despite falls this February, their share prices are also mostly ahead of the ASX 200 in 2025.

In this piece, we are going to look at the profit results and quarterlies released by the banks in February 2025 and see if doom for the bank share prices finally occurs in 2025.

February 2025 reporting season

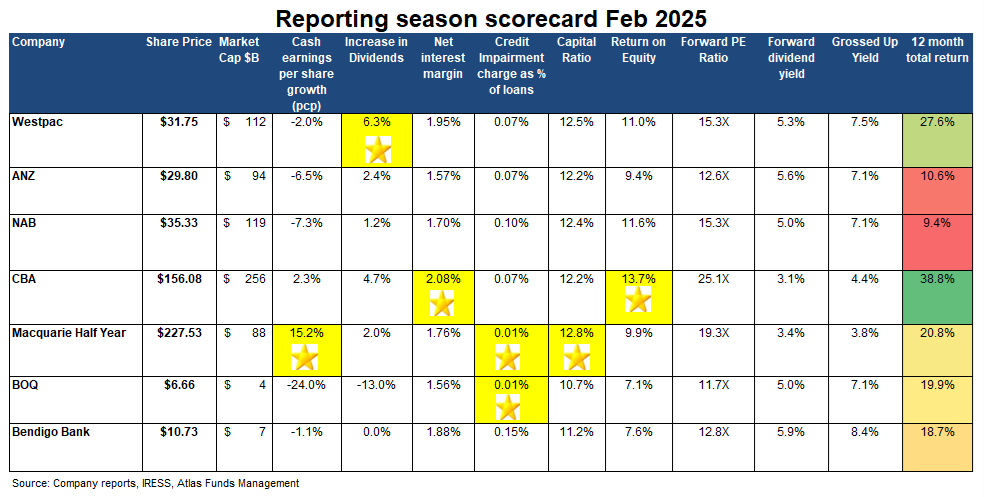

Over the last month, Commonwealth Bank and Bendigo Bank reported audited financial results for the six months ended December 2024, with the other banks giving unaudited quarterly updates. Quarterly updates can be misleading both positively and negatively, and generally show a lower level of capital than will be reported at the full half, reflecting a newly paid dividend and only three months of organic capital generation. Further, the quarterlies have offered limited and inconsistent disclosure of key metrics such as bad debts and net interest margins.

In early February, CBA reported very strong results, with higher profits, dividends, margins, and minuscule bad debts. However, given the company's lofty valuation, there was no room for error. This saw CBA's share price increase to $166 per share.

However, a week later, NAB sent tremors through the banking sector after releasing a quarterly report revealing higher impairments against business loans and a contracting net interest margin. While the large fall in the share price was unpleasant for NAB shareholders, Bendigo Bank had a rougher month, down 19% after revealing a 10% drop in profits due to higher expenses. Atlas tends to avoid owning the regional banks as they have a structural disadvantage compared to the major banks, with higher funding costs, lower IT and risk management resources, lower margins and a lower return on equity.

Bad debts will rise one day

The low level of bad debts from banks has continually surprised the market over the past five years due to a combination of prudent lending, APRA guidelines, house price appreciation, and the fact that residential loans in Australia are ‘recourse-based’ lending. This means that if the mortgage holder defaults on their home loan and the proceeds from the property sale do not cover the bank's debt, the bank can pursue the borrower for the residual owed.

Since 2021, the major banks have reported bad debt expenses between 0% and 0.2%, the lowest in history and clearly unsustainable. Excluding the property crash of 1991, bad debt charges through the cycle have averaged 0.3% of gross bank loans for the major banks, with NAB and ANZ reporting higher bad debts than Westpac and CBA due to their greater exposure to corporate lending.

In predicting the trajectory of bad debts in 2025, the 1989-93 spike should be excluded, as these were due to a combination of poor lending practices and very high interest rates. Indeed in 1991, the head office of Westpac was unaware of the concentration risk from different arms of the bank simultaneously lending to 1980s entrepreneurs such as Bond and Skase.

During this period, borrowers saw interest rates approaching 20%, a level outside any current forecasts. Today, the composition of Australian bank loan books is considerably different to what they were in the early 1990s or even 2007, with fewer corporate loans (such as to ABC Learning, Allco, and MFS) and a greater focus on mortgage lending, which is secured against assets and historically has very low loan losses. Additionally, the major banks have pulled the plug on their foreign (mis) adventures, with no exposure to northern England and Asia, which in 2008, saw high bad debts, often due to the making of questionable loans outside of the core market.

While unemployment remains low, Atlas expects banks' loan losses will remain low, particularly when much of the more ‘exciting’ high-yield lending to developers is not on bank balance sheets but with private credit funds. A new investment class that has emerged seriously in the past five years.

The size of the private credit market has exploded to be around $40 billion. While the prospects for private credit funds invariably attributes their growth due to these funds being more nimble and smarter lenders than the banks, which sees private credit funds winning new borrowers over the staid major banks, the real reason for the emergence of private credit funds is far less exciting.

After the Basel III banking accords were designed to improve the stability of global banks, Australian regulators have largely forced banks out of lending to riskier borrowers such as property developers by forcing banks to set aside high levels of capital against poorer credit loans. Consequently, the return on equity (ROE) measures of loans to property developers with limited pre-sales are unattractive for the major banks to make. Conversely, private lenders are not regulated by APRA or the RBA and have happily stepped into this void.

Indeed, over the past year, we have seen some aggressive practices utilised by certain private credit funds to avoid reporting losses on impaired assets, which the author last saw in the final months of Allco and Babcock & Brown fifteen years ago. Pre-GFC, these problematic loans that were made by private credit funds would have been made by major banks. Clearly, the rise of private credit funds has contributed to low bank bad debts over the past few years and likely lower-than-expected bad debts in the near future.

Banks structurally safer in 2025

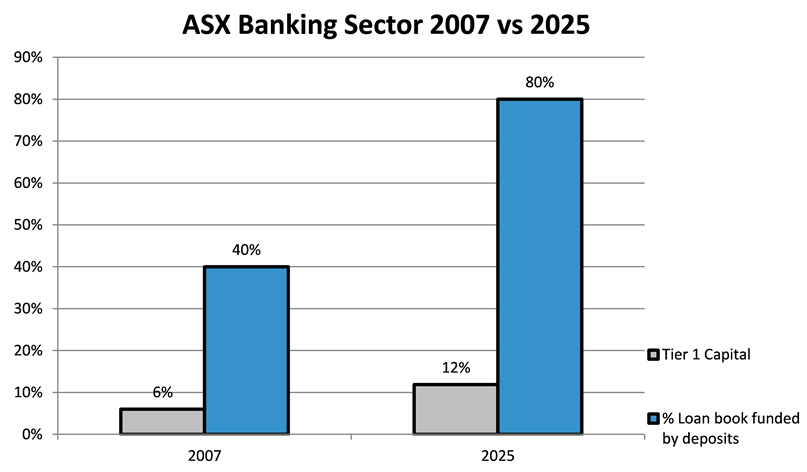

In 2025, all banks have a core Tier 1 capital ratio above the APRA 'unquestionably strong' benchmark of 10.5%. This allowed Australia's banks to enter the event of COVID-19 in 2020 and then the 2022-24 rising rate cycle with a greater ability to withstand an external shock than was present in 2007 going into the GFC, where their Tier 1 Capital ratios were around 6%.

For investors, this is important as the banks have more capital backing their loans in 2025 than in 2007. It means that the chance of a bank either becoming insolvent or being forced to raise dilutive equity is reduced. Additionally, the quality of the loan books of the major banks is higher in 2025 than in 2007 or 1991, which saw a greater weighting to corporate loans with higher loss levels than mortgages.

Foreign banking adventures that have caused investor heartaches in the past have largely ceased, with NAB pulling out of Europe and CBA and ANZ selling stakes in Asian banks. Further, as discussed above, the more ‘exciting’ mezzanine loans to property developers, which were on bank loan books in 2007, now substantially reside in the loan books of private credit funds.

Additionally, the banks' funding source is more stable today than it was 15 years ago, with an average of 80% of loan books funded internally via customer deposits. This means that the banks rely less on raising capital on the wholesale money markets (typically in the USA and Europe) to fund their lending. Pre-GFC, the banks funded around 25% of their lending from the short-term wholesale market, effectively borrowing short and lending long, based on the assumption that this short-term debt can be easily and cheaply refinanced. An assumption that caused RAMS' demise in 2007.

Since the GFC, the banking oligopoly in Australia has only become stronger, with foreign banks such as Citigroup exiting the market and smaller banks such as St George, Bankwest, and now Suncorp being taken over by the major banks.

Politicians occasionally bemoan Australia's concentrated banking market structure, with 75% of lending being done by big four banks plus Macquarie and point to the 4,600 banks in the USA on the assumption that a vast amount of small regional banks would deliver more lending competition. However, a feature of the US system is regular bank collapses, with the Pulaski Savings Bank in Illinois in January being the first bank failure of 2025 and the fifteenth since 2019! Conversely, the last bank collapse in Australia was the State Bank of South Australia in 1991. Indeed, a strong, well-capitalised banking sector looked to be very desirable in 2023 with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in the USA and UBS' forced takeover of Credit Suisse.

Buybacks provide a backstop

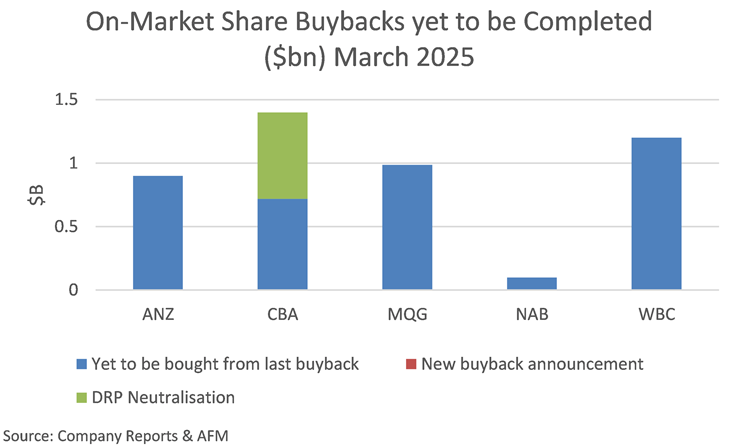

One of the factors not considered 12 months ago by the experts advising investors to sell all of their bank shares was the impact of on-market share buybacks. All the major banks have capital in excess of regulatory requirements, which have built up since the 2018 Royal Commission as the banks exited non-core businesses such as wealth management and insurance, and provisions for Covid-19 losses went unused. Over the past year, this excess capital has been channelled into on-market share buybacks, where $5.1 billion of bank shares were bought and cancelled, effectively creating a new and consistent buyer.

Atlas sees that share buybacks are preferable to the sugar hit of a one-off special dividend as they reduce the dividend for future profits and are infinitely preferable to management teams spending shareholder capital on questionable acquisitions. The Australian banks' track record of exporting their domestic banking brilliance to other markets has a very checkered history.

Currently, close to $4 billion of share buybacks are still underway, with all banks, with the exception of Macquarie, actively buying back their own stock on the ASX. The quantum of this buyback is likely to be expanded in May when ANZ, NAB, Macquarie and Westpac report their financial results. Swimming against the tide of on-market share buybacks was a poor investment strategy in 2024.

Our take

Atlas was pleased with the bank results we saw in February 2025, mainly from CBA, and expects the upcoming May reporting season to show that the three banks that gave quarterly reports are also in good shape. We don't expect the banks to perform in 2025 as they did in 2024, but they are likely to hold up well in what we see to be a flat market for Australian shares in 2025, supported by their dividend yield and ongoing buybacks, particularly on share price weakness. With an average grossed-up yield of +6.5% and lower-than-expected bad debts, bank shareholders will be rewarded for their patience and for ignoring the current market noise.

Hugh Dive is Chief Investment Officer of Atlas Funds Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.